The United National World Tourism Organisation released a tender document in July 2010 (UNWTO 2010) that called for the development of a global approach to and implementation of a best practice guide for the integration of tourism into national emergency structures and processes. The UNWTO’s proposal for a formalised integrative approach represents a major advancement in global tourism approaches to risk and crisis management. At an informal level, considerable cooperation occurs between government tourism agencies and private tourism businesses and emergency management providers. In specific cases, notably with airlines and airports integration has been practiced in a structured manner for decades. Integrative practices have also been commonplace for mega events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup.

Despite the significant growth of global tourism since 1970, the management of risk and crisis has rarely been accompanied by commensurate integrative policies between the tourism industry and emergency management agencies. During the first decade of the 21st century an upsurge of crisis events have impacted on and involved tourism. Some include natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and most notably tsunami events in which tourists and tourism infrastructure have figured prominently in damage and casualty figures. The tendency for large concentrations of tourism infrastructure to be located in regions (Weaver and Lawton 2010) referred to as the pleasure periphery make them highly vulnerable to storms and climatic extremes. The pleasure periphery refers primarily to coastal areas in warm-tropical climate areas which are often subject to cyclones, typhoons and hurricanes (depending on their geographic location).

Tourism and tourists are increasingly targeted by terrorists and criminals. The terrorist threat is a particular concern for tourism as the core aim of terrorist violence is the achievement of international publicity for their actions and the religious or ideological cause of the perpetrators. Consequently attacks on attractions, hotels, entertainment centres, transport hubs and other places where international tourists gather ensures that victims will be from a variety of countries and as a consequence the publicity generated will be global in scope. Tourists are also considered to be soft target for criminals who target the perceived and actual anomie of tourists in an unfamiliar environment. US Tourism security expert Dr Peter Tarlow, has developed tourism oriented policing training programs in the United States that are designed to heighten the sensitivity of policing to the special circumstances of tourists especially in those areas that attract a high density of domestic and international tourists (Tarlow 2006 and 2010).

The October 2002 Bali bombing vividly illustrated the need to effectively integrate tourism and emergency services. The killing of 200 tourists and the wounding of over 300 more was beyond the capabilities of Bali’s medical, emergency rescue, police, ambulance and hospital services to cope with a disaster of this scale (PATA 2003). Clearly, a terrorist attack on this scale would have stretched the capacity of emergency services in any jurisdiction in the world. However Bali, in common with many destinations catering to mass tourism, is characterised by a level of integration between tourism and emergency services which is rudimentary at best. Heavily visited tourist destinations frequently lack an emergency management infrastructure to match the number of visitors.

Tourism has also been a significant contributing factor in the rapid spreading of infectious diseases. The recent H1N1 (Swine Flu) outbreak, initially identified in Mexico in April 2009 had spread to over 100 countries by the end of that year. The rapid global spread of this disease was largely attributable to tourists, many of whom were unaware they had H1N1 symptoms when they travelled. Heat sensors which were deployed at airports around the world frequently failed to identify people with the disease in its earliest stages. In many countries affected by pandemics (even those as relatively benign as H1N1) there is little integration between tourism and emergency management services on matters as basic as patient quarantine or isolation. Some obvious linkages between tourism and emergency services would be hotels having mandatory contacts with medical, police, fire and other emergency services. Although Australia has taken this issue seriously, many countries with high concentrations of tourists impose few regulations.

The concept of tourism and emergency management integration is a two way process. Emergencies that impact on residents in any given locality are equally likely to impact on tourists. While residents are normally easy to locate and identify by local emergency agencies, tourists by virtue of their transient presence are not. During a natural disaster tour operators, accommodation providers and transport providers have an important role to play in identifying tourist victims and confirming those visitors unaffected by a natural disaster. Tourist facilities can play a positive role in providing emergency accommodation and refuge, evacuation transport by land, sea or air in the event of natural disasters or human caused crisis events.

The Australian tourism industry at both government and private sector level has (with the notable exceptions of the airline and airport sector and mega events) been somewhat remiss in addressing collaboration between emergency services and tourism. The Australian Government’s National Tourism Industry Incident Response Plan (Australian Dept of Resources Energy and Tourism 2007) focuses its attention on crisis communications and reputation management in its response to crisis events. Important as these issues are to the management of tourism related crisis events there is no discussion collaborative or integrative links between tourism authorities and businesses and emergency services. The absence of such a link is even more inexplicable in view of the consultation which the authors allege took place with Emergency Management Australia. The absence of an integrative approach to crisis events is equally prevalent at a global level. The UN World Tourism Organisation’s decision to develop a policy approach in 2010 is recognition that the lack of an integrative approach between tourism and emergency management services requires urgent attention.

The APEC Tourism Risk Management Guide (APEC 2006) referred to a number of cases in the Asia/Pacific region in which the tourism industry was involved on a consultative basis with the Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre and the Tourism Disaster Response Network which was established in January 2005. With the exception of the International Civil Aviation Organisation the connection between the tourism industry and Emergency services tends to be informal and consultative rather than formalised and integrative. As Dr Alison Specht correctly points out (Specht 2006), “Active (tourism industry) participation in regional planning and disaster management teams will ensure that the needs of the tourism industry are understood and incorporated sensibly into planning. A strong, effective, regional (world, country. state or smaller) tourism body which actively engages with its members and with other organisations can be an insurance policy in itself”.

In Australia, an example of the integrative model between emergency management and tourism exists to a limited extent with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Smartraveller Advisory Group. The *Smartraveller Advisory Group was established in 2003 following negotiations between DFAT and the leadership of Australia’s key outbound travel industry associations and companies. Initially, the primary role of the Smartraveller Advisory Group was to assist DFAT in the dissemination of Australian government travel advisories for Australian citizens travelling internationally. Although this remains the primary role of SAG, it has increasingly worked with DFAT to provide a travel industry dimension in emergency management for Australian victims of crisis events abroad. This includes airlines and tour operators being requested by DFAT to either waive or ease cancellation or change restrictions to facilitate the evacuation of Australians in danger from natural disasters, episodes of terrorism, political instability or regional conflict. It also includes travel organisations being asked to urge Australians travelling abroad to register their itinerary on the Smartraveller website so that they can be contacted in the event of a major threat to their safety. DFAT works closely with emergency management and tourism organisations globally to ensure that Australian’s involved in disasters or emergency situations in foreign countries can be rendered assistance. The Insurance Council of Australia plays an important role in working with DFAT. DFAT’s message to outbound travellers to purchase appropriate travel insurance policy is a core message of the Smartraveller campaign.

The integration between the tourism industry members of the Smartraveller Advisory Group and DFAT’s own crisis management unit is very limited in scope but the consultative relationship that SAG represents is a move towards a integrative process. In the outbound travel context Australian tourism organisations are still highly dependent on the co-operation of emergency management agencies and tourism industry principals at the various destinations.

The process of developing an integrative approach to tourism and emergency services starts with a bilateral assessment of how emergency management services can assist the tourism industry and how tourism businesses can assist and enhance emergency management capability.

Capabilities and Services Tourism Businesses are able to provide Emergency Management Services and Agencies:

Capabilities the Tourism Industry requires from Emergency Management Agencies:

Although both lists are indicative only, these examples demonstrate that the integration of tourism and emergency services is genuinely bilateral. The tourism industry and emergency service agencies have the capabilities to enter into a mutually productive alliance in many jurisdictions with a high density of tourists and a substantial tourism infrastructure. The overall planning of emergency services infrastructure and staffing should consider the number of tourists and the extent of tourism infrastructure as integral to the planning process.

One lesson been noted but not fully acted upon from recent tsunamis in the Indian and Pacific Oceans is the importance of building regulations on coastal tourism resorts and accommodation facilities to avoid building structures on locations vulnerable to sea inundation. Unless regulations are enacted and enforced as was the case in Phuket, after the 2004 tsunami, (Gurtner 2007) resort developers will frequently construct and site accommodation that is vulnerable. The tourism market demand for waterfront or on-sea accommodation is often more powerful than architectural common sense.

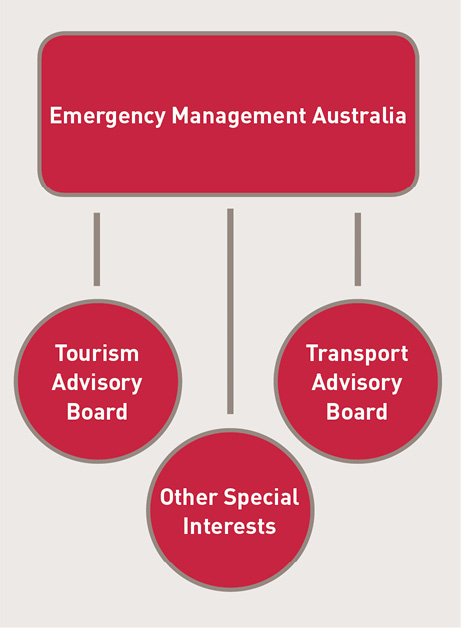

Figure 1. The Consultative Model Linking EMA with tourism and other special interest groups.

An important element in an integrative program between emergency service agencies and tourism is the capacity for emergency service agencies to train selected staff in tourism business the basic skills of emergency procedures relevant to their operational needs. This not only enhances the emergency response capability within a given jurisdiction but it means that tourists who may be affected by a natural or a human sourced crisis event are able to receive instant assistance prior to deployment of emergency services.

Successful and effective integration between emergency management and tourism could take one of two paths. One path may best be described as the consultative path. This would involve a tourism industry consultative board to emergency management agencies in a given jurisdiction. Applying this at the Australian national level, a tourism advisory board to Emergency Management Australia or the Australian Emergency Management Institute may include such organisations as The Tourism Department within DRET, Insurance Council of Australia, Tourism and Transport Forum, National Tourism Alliance, Australian Federation of Travel Agents, Australian Hotels Association, Australian Tourism Export Council (the association of inbound Australian tourism), key domestic airlines, Cruise Council of Australia and the Australian Society of Travel Writers.

Communication with and the education of tourism professionals and the public on emergency management matters is as important as practicing emergency management procedures. This group would meet at scheduled intervals to map out an overall linkage policy between the tourism industry and emergency services. In the event of a major crisis, especially one with a tourism dimension the members of the Advisory group may be co-opted to be involved in undertaking emergency management roles. In effect this would work in a similar fashion in an inbound dimension as the Smartraveller Advisory group does in conjunction with DFAT for outbound travel.

The primary advantage of this path is that a broad range of key tourism organisations would be sensitised to the role they need to play in working with emergency management services. It would present an opportunity for those associations and organisations involved in the consultative process to pass on information and approaches to emergency management to their constituents.

The main disadvantage of this path is that it does not represent true integration between tourism and emergency management. Its role is primarily advisory and it involves relatively little accountability on the part of the tourism industry and tourism authorities to consider emergency management as core role in tourism businesses. The consultative path would represent an intermediate stage towards integration rather than an end point.

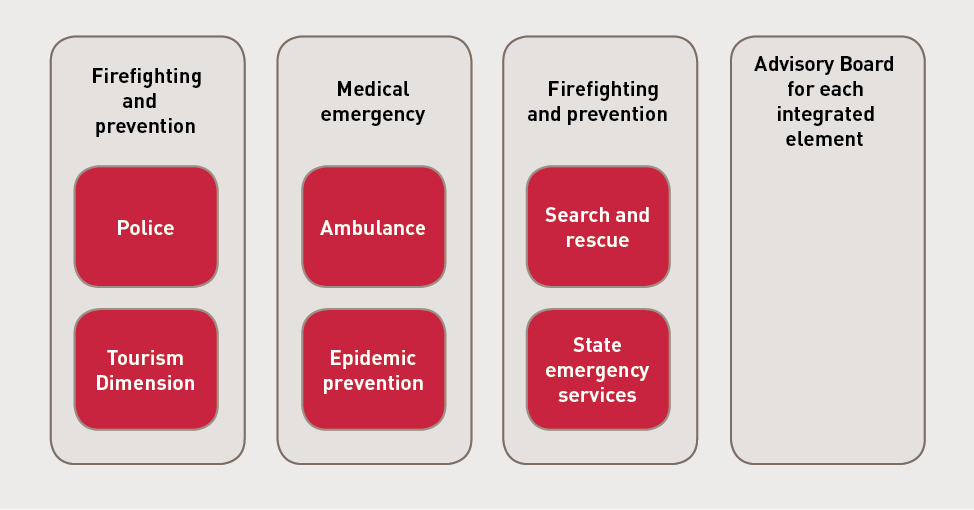

The second path or option would involve tourism industry representatives playing an integral role in emergency management planning and response in all jurisdictions and as integral members of Emergency Management Australia or the Australian Emergency Management Institute. In this case the number of representatives would be limited and ideally would need to be authorised by a broad cross section of the tourism and hospitality industry to effectively represent the combined interests and concerns of the tourism industry. The ongoing involvement would represent a more integrative approach than the consultative path. It would also mean that tourism industry resources and interests would always be considered as an integral part of emergency management planning and policy. In the event of international visitors being victims of any emergency situation the diplomatic legations require readily available information on the status of their nationals within a given jurisdiction.

Figure 2. Tourism within an Integrative Approach to Emergency Management.

A key benefit of the fully integrative model is that tourism is factored in as an essential element of any emergency management structure and procedure and would be an integral part of the mobilisation strategy immediately in the event of an emergency situation.

The possible disadvantage of tourism representatives being fully integrated into the emergency management structure is the possibility that the tourism representative/s may not fully represent all sectors of the industry. In practice, the tourism industry is subject to atomisation in that airline people often feel tourism revolves around airlines and hoteliers tend to believe tourism revolves around accommodation.

The intent of this paper to advance the proposition that tourism is central to emergency management and planning, not a peripheral issue. Airports include key emergency management resources and personnel on hand. A major airport authority would be perceived to be failing in its duty if it lacked fire fighting, security, ambulance and rescue resources either on-site or nearby. International gateway airports in their role as international border entry points incorporate a significant involvement of staff from many branches of government including immigration, customs, police, defence agencies and health authorities among others. The airline and airport industries represent an element of the tourism industry in which integrative practices between the industry and emergency services is standard practice. Organisers of mega events from major sporting events to events such as World Youth Day involve a high level of integration. Tourism academic Joan Henderson has pointed out that the tourism industry needs to build working crisis management partnerships from outside the industry to optimally manage the crises of the future.

Integration between tourism and emergency management should involve all sectors of tourism. Tourism and hospitality associations and businesses have resources which can make a valuable contribution to the planning and implementation of emergency management policy and procedures. The tourism dimension of crisis events and disasters includes national and international implications. Tourists (be they domestic or international) have a very high likelihood of being victims of emergency situations. Their lack of familiarity with a destination region, local customs, language or a lack of awareness of local security risks and threats often result in the tourists having a higher propensity to find themselves in dangerous situations than many local residents. Emergency services and agencies need to have a keen awareness of the tourism dimension of their role. Enhancing integration between the tourism industry and emergency agencies is mutually beneficial in terms of emergency readiness and response.

Australian Dept of Resources, Energy and Tourism, 2007, National Tourism Industry Incident Response Plan. Australian Dept. of Resources , Energy and Tourism, Canberra.

Beirman, D, 2010 Crisis, Recovery and Risk Management. Chapter 11. Understanding the Sustainable Development of Tourism . Eds. Liburd, J. Edwards, D. Goodfellow, London pp 205-224

Gurtner, Y, 2007, Phuket, Tsunami and Tourism- A Preliminary Investigation,. Chapter 14. Laws, E. Prideaux, B. Chon K., Crisis Management in Tourism. Cabi Publishing Wallingford UK. pp. 217-233

Henderson, J, 2007. Tourism Crises Causes, Consequences & Management. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Robertson, D. Kean, I,. Moore, S, 2006, Tourism Risk Management- an Authoritative Guide to Managing Crisis in Tourism, APEC International Centre for Sustainable Tourism, Singapore

Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) 2003, Report of the PATA Bali Taskforce. PATA Bangkok. Can be accessed via www.pata.org

Rossnagel, H. Junker,). 2010 Evaluation of a Mobile Emergency Management System- A Simulation Approach. Paper at the 7th International ISCRAM Conference- Seattle USA May 2010.

Specht, A, 2006, Natural Disaster Management. Chapter 9, Tourism in Turbulent Times-Towards Safe Experiences for Visitors. Eds Wilks, J. Pendergast, D. Leggatt, P. Elsevier, Amsterdam. pp 123-142.

Tarlow, P, 2010 Tourism Orientated Police Services . A presentation given at the International Tourism Security Summit,. Kuala Lumpur Malaysia June 14. 2010. Organised by the Egnatia Academy, www.tourism-summit.com

Tarlow, P, 2006, Crime and Tourism. Chapter 7, Tourism in Turbulent Times- Towards Safe Experiences for Visitors, Eds. Wilks, J. et al. Elsevier , Amsterdam pp 93-106

UN World Tourism Organisation, 2010. Integration of Tourism into National Emergency Structures and Processes. Recommendations and Best Practices.. Invitation to Tender. UNWTO Madrid.

Weaver, D., Lawton, N., 2010 Tourism Management 4th Edition. John Wiley & Sons. Brisbane p 83

Dr David Beirman is a Senior Lecturer in Tourism at the University of Technology-Sydney. His specialist field is tourism risk, crisis and recovery management. Beyond the university he is a “founder” and active member of the *Smartraveller Advisory Group which has operated as an ongoing liaison between the Australian outbound tourism industry and DFAT since 2003 . He is the founder and National Secretary of the Eastern Mediterranean Tourism Association.