The author recently researched the community learning delivery approaches of most of the State and Territory emergency management agencies in Australia. He found that emergency agencies tend to centre their community learning delivery activities either around an ‘engagement’ approach or an ‘education’ approach. Several of the agencies have developed and are implementing either community engagement or education strategic plans.

This article explores what is the best approach for emergency agencies: engagement or education? It also briefly examines the potential of new (social) media in supporting both approaches.

There are many definitions of community disaster resilience in the literature. In this article, community disaster resilience is defined as the ability of a community to not only resist and recover from a disaster, but also to improve as a result of the changed realities that the disaster may cause.

In December 2009, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to ‘adopt a whole-of-nation resilience-based approach to disaster management, which recognises that a national, coordinated and cooperative effort is needed to enhance Australia’s capacity to prepare for, withstand and recover from disasters. The National Emergency Management Committee subsequently developed the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience which was adopted by COAG on 13 February 2011.’

The purpose of the Strategy is to ‘provide high-level guidance on disaster management to federal, state, territory and local governments, business and community leaders and the not-for-profit sector. While the Strategy focuses on priority areas to build disaster resilient communities across Australia, it also recognises that disaster resilience is a shared responsibility for individuals, households, businesses and communities, as well as for governments. The Strategy is the first step in a long-term, evolving process to deliver sustained behavioural change and enduring partnerships’ (Attorney-General’s Department website: www.ag.gov.au).

The Strategy (COAG, 2011) identifies seven groups of actions to build community disaster resilience in Australia.

Learning–both within emergency agencies and with communities–has a critical role to play in building disaster resilience. This claim is supported by the focus on resilience-building in the national learning programs developed and implemented by the Australian Emergency Management Institute (AEMI). AEMI ‘continues to focus on improving knowledge and development in the emergency management sector. It supports broader national security capability development efforts to build community resilience to disaster’ (Attorney-General’s Department website: www.ag.gov.au).

Although usually attributed to changing community behaviours (e.g. for preparedness, response and recovery) in emergency management, learning can play a strong role across all seven disaster resilience-building actions in the Strategy.

As noted on page 3 of the Strategy, ‘emergency management in Australia is built on the concept of prevention, preparedness, response and recovery (PPRR)….preparing for each of these elements of emergency management helps build resilience.’ The contribution of emergency agencies to community disaster resilience learning through engagement and education therefore should be related to PPRR.

However, PPRR is only one element–albeit a critical one–in building disaster resilience. Other participants are required to build disaster resilient communities across Australia through a change to shared responsibility. ‘The fundamental change is that achieving increased disaster resilience is not solely the domain of emergency management agencies; rather, it is a share responsibility across the whole of society’ (COAG, 2011, p.3). There is therefore a need for disaster resilience learning to be delivered in a coordinated manner between State and Territory emergency agencies other relevant agencies, the Australian Government (e.g. through AEMI, Bureau of Meteorology), local councils, insurance industry, non-government organisations (e.g. Red Cross, volunteering organisations), and with the participation of community groups and individuals.

Is engagement or education the best way for emergency agencies to deliver their responsibilities in community disaster resilience learning?

Engagement involves processes that inform, consult, involve, partner with and empower communities (International Association for Public Participation, 2004). A major benefit of engagement is that it can include activities where communities participate in decision-making and share responsibility. Several studies during the past fifteen years have found the traditional approach to emergency management of ‘top-down’ provision of information to be relatively ineffective. According to O’Neill (2004), this approach ‘was often one-off and one-way, and assumed that the audience was an undistinguishable group of individuals who had the same needs and values.’

The traditional approach is based on the premise that raising individual awareness will lead to preparedness and response behaviours. According to Paton et al. (2003), ‘It is frequently assumed that providing the public with information on hazards and their mitigation will encourage preparation. This assumption is unfounded.’ Several researchers, such as Boura (1998), have demonstrated that there is not a strong and causal link between receiving information and acting appropriately for hazards.

A more participatory approach to the delivery of community learning by emergency agencies is now being promoted. According to Paton (2006), ‘Participation in identifying shared problems and collaborating with others to develop and implement solutions to resolve them engenders the development of competencies (e.g. self-efficacy, action coping, community competence) that enhance community resilience to adversity.’

Education in this article involves planned activities that lead to prescribed learning outcomes. Based on education theory (e.g. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains) and recent research into emergency management education (e.g. Dufty, 2008), learning outcomes relevant to disaster resilience-building are generally related to awareness-raising, skills development, behaviour change, attitudinal change and values clarification.

A major benefit of education is that it can be specifically targeted to measurable learning outcomes. For example, education programs can be designed to raise community awareness of disaster risk and for appropriate disaster response behaviours e.g. through evacuation drills.

Table 1 provides an insight into the similarities and differences between engagement and education processes and activities as used by emergency agencies.

Table 1. Some differences and similarities between community engagement and education approaches that could be used by emergency management agencies.

|

ENGAGEMENT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Processes |

Informing |

Consulting |

Involving |

Collaborating |

Empowering |

|

Example activities |

Fact sheets, websites, displays, presentations |

Focus groups, surveys, public meetings |

Workshops |

Committees, citizen advisory panels |

Citizen juries, delegated decisions |

|

EDUCATION |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Processes |

Awareness-raising |

Developing skills |

Behaviour change |

Attitudinal change |

Values clarification |

|

Example activities |

Fact sheets, websites, displays, presentations |

Training, simulations |

Emergency plans, emergency drills |

Opinion pieces, debates, role plays |

Visioning, values surveys |

As shown in Table 1, there is a strong nexus between the engagement process of informing and the education process of awareness-raising (sometimes called ‘top-down’ delivery). Generally, they involve similar activities for emergency agencies. However, due to differences in their intent, the other engagement and education processes can have quite different activities.

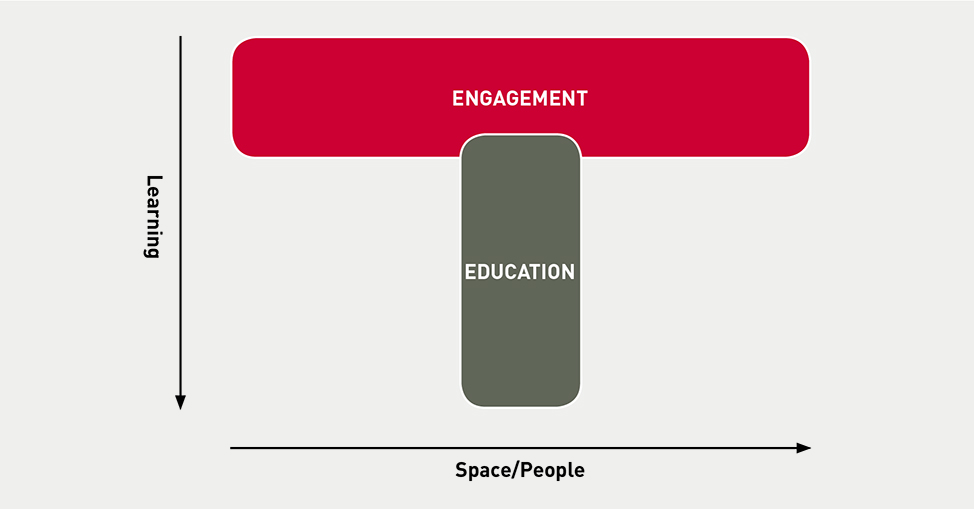

Furthermore, the learning impacts in communities from engagement and education can be quite different. Generally, engagement by itself will provide unplanned learning for disaster resilience; education will provide planned learning for disaster resilience. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A theoretical representation showing how engagement provides 'breadth' and education provides 'depth' to community disaster resilience learning.

Figure 1 also highlights the limitations of both engagement and education in learning for disaster resilience. As shown, engagement by itself enables interactions across communities (‘breadth’ of delivery) but only provides a relatively ‘shallow’ level of unplanned learning. On the other hand, education provides ‘depth’ in community learning related to specific learning outcomes. However, due sometimes to resourcing issues (e.g. many education programs are financed by grants) and the need for expert educators to design specific programs (e.g. for schools, vulnerable groups, businesses), it is generally difficult to extend effective education programs across broad areas.

As shown by recent studies (e.g. Elsworth et.al., 2009), it is when engagement and education processes and activities are combined there is potency in impact. For example, a focus group or survey may identify and lead to a particular education activity such as an emergency drill to help build resilience. Also, engagement and education activities can be coupled together e.g. a community event to increase preparedness levels could involve elements of engagement (e.g. talking with people) supported by an education activity (e.g. how to prepare a home emergency plan).

Based on the above analysis it would be prudent for emergency agencies to include engagement and education processes in their delivery of community learning to gain ‘breadth’ and ‘depth’ of learning across communities. The impact of this delivery should be heightened through the coupling of both approaches.

After reviewing several engagement and education strategies prepared by Australian emergency agencies, it appears most utilise processes from both approaches, including in conjunction with each other. However, it could be worthwhile for agencies to consider this analysis (e.g. in Table 1) as they evaluate their community learning delivery strategies to enable improved precision in choosing appropriate and potentially effective processes from both approaches. There may also be value in using the title ‘engagement and education strategic plan’ in recognition of the use of both approaches.

Social media such as Facebook and Twitter have been used extensively in the past few years by emergency agencies to engage with and educate users, particularly in relation to disasters such as the 2011 earthquakes in Japan and Christchurch, the 2010 Haiti earthquake and the 2011 Queensland and Victorian floods. For example, the Queensland Police Service (QPS) used Facebook and Twitter to help issue warnings, send out response messages and support flood-impacted residents through dialogue at the height of the 2011 Queensland flood disaster. To give some idea of the impact of this, there were apparently over 14,000 tweets mentioning ‘QPSMedia’ during the floods and Twitter followers increased from 2,000 to almost 11,000 followers in 25 days (similar striking increases occurred for the QPS Facebook site). Interestingly, a large proportion of the Facebook and Twitter users were under 50 years of age and about 75 percent were female.

Social media such as Facebook and Twitter have been used extensively by emergency service agencies.

Social media appear to be tools that can deliver all of the ten engagement and education processes listed in Table 1. Social media rely on peer-to-peer (P2P) networks that are collaborative, decentralised, and community-driven. They transform people from content consumers into content producers. Using social media emergency agencies can inform, consult, involve, collaborate with and empower users. All five education processes in Table 1 can also occur through ongoing dialogue. Furthermore, social media enable a seamless and organic linkage between engagement and education processes as promoted above.

Several Australian emergency agencies including the QPS, the NSW Rural Fire Service and the Victorian Country Fire Authority are using social media for engagement and education. This trend should be encouraged with social media added to the traditional engagement and education activities used by emergency agencies, some of which are listed in Table 1.

A major weakness of engagement and education activities and programs delivered by Australian emergency agencies is lack of evaluation. The National Review of Community Education, Awareness and Engagement (EAE) Programs for Natural Hazards conducted by RMIT University for the Australian Emergency Management Committee (Elsworth et. al., 2009) found ‘close to 300 separate programs and activities for natural hazard community education, awareness and engagement. Evaluation studies of 14 of these initiatives were located and reviewed in detail’.

The EAE Review report concluded that ‘systematic monitoring and evaluation of community education, awareness and engagement programs for natural hazards is the exception rather than the rule. Some agencies have good systems for monitoring activities and the dissemination of information; however research into outcomes in terms of effectiveness of the information in changing attitudes, patterns of thinking, and behaviours is fairly scarce’.

Emergency agencies should ensure that evaluation is built into all engagement and education programs and activities in their strategic plans.

Most emergency agencies in Australia have an engagement or education strategic plan to deliver community learning. These agencies have an important role to play in community learning around PPRR as part of broader disaster resilience learning guided by the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience.

It is recommended that emergency agencies:

Boura, J., 1998, Community Fireguard: Creating partnerships with the community to minimise the impact of bushfire, The Australian Journal of Emergency Management Volume 13, pp. 59-64.

COAG, 2009, National Disaster Resilience Statement, Excerpt from Communique, Council of Australian Governments, Brisbane 7 December.

COAG, 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Building our nation’s resilience to disasters, Council of Australian Governments, 13 February.

Dufty, N., 2008, A new approach to community flood education, The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, Vol. 23 No. 2, May 2008.

Elsworth, G., Gilbert, J., Robinson, P., Rowe, C., and Stevens, K., 2009, National Review of Community Education, Awareness and Engagement Programs for Natural Hazards, report by RMIT University commissioned by the National Community Safety Working Group of the Australian Emergency Management Committee.

International Association for Public Participation, 2004, IAP2 Public Participation Spectrum, available on the IAP2 Australasia website: www.iap2.org.au.

O’Neill, P., 2004, Developing a Risk Communication Model to Encourage Community Safety from Natural Hazards, NSW State Emergency Service paper.

Paton, D., Smith, L., Johnston, D., Johnston, M., & Ronan, K., 2003, Developing a model to predict the adoption of natural hazard risk reduction and preparatory adjustments, (Research Project No. 01-479): EQC Research Report.

Paton, D., 2006, Community Resilience: Integrating Hazard Management and Community Engagement. Paper from School of Psychology, University of Tasmania.

Neil Dufty is a Principal of Molino Stewart Pty Ltd. He has extensive experience in the development and implementation of community engagement and education strategic plans across Australia. During the past eight years he has reviewed community engagement and education strategic plans, programs and activities for several emergency agencies including VICSES and NSW SES. He can be contacted at ndufty@molinostewart.com.au