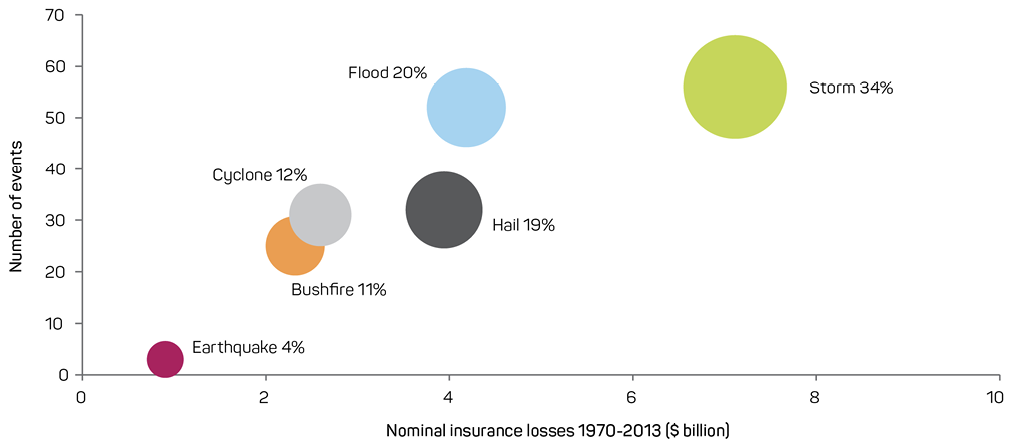

Australia’s annual insured losses due to natural disasters exceed $480 million on average (ICA 2014), continuously highlighting the need for well-designed homes and infrastructure. Cyclone and severe storm events are particularly costly, contributing to nearly half of all nominal natural hazard insurance losses over the period from 1970–2013 (see Figure 1).

While cyclone events are relatively infrequent, the resulting losses are excessive and the risk associated with insuring properties in cyclonic regions of Australia (e.g. Queensland) has led to affordability issues. For Suncorp, the average offered premium price for new business homes in north Queensland is $2500 annually. Many studies by academic, private and government organisations within Australia and abroad suggest that a focus on pre-disaster mitigation can reduce building stock vulnerability (Australian Government Treasury 2015, Smith, Henderson & Ginger 2015a, Smith, Henderson & Ginger 2015b). This can reduce cyclone-induced losses and allow for risk-reflective insurance pricing (i.e. lower premiums for stronger houses). Indeed, some engineering approaches for improving vulnerability already exist (Standards Australia, 1999a, b) but are not widely implemented.

Investigating the psychology of natural hazards, Kunreuther and colleagues (2009) suggest the shortage of homeowner investment in risk reduction may be due to a lack of risk awareness, underestimation of risk, budget constraints, and difficult computations for cost-benefit trade-offs. There are also other psychological and situational barriers in the decision-making process. In 2014, Suncorp Insurance and the CTS began a collaborative research effort to investigate and reduce the engineering, financial and psychological barriers to widespread vulnerability reduction and insurance affordability in Queensland.

The first phase of the research involved claims analysis from cyclones Yasi and Larry to identify key engineering vulnerabilities in Queensland housing (Smith & Henderson 2015b). One of the more costly storms in Australian history, Cyclone Yasi, resulted in estimated economic losses of over $2 billion, with insured losses of over $1.4 billion (see Table 1).

| Event | 2011 Normalised Economic Loss $m | 2011 Normalised Insured Loss $m | Insured % | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cyclone Larry |

1,692 |

609 |

36% |

March 2006 |

|

Cyclones George and Jacob |

N/A |

12 |

N/A |

March 2007 |

|

Cyclone Yasi |

2,080 |

1,469 |

71% |

February 2011 |

|

Cyclone Oswald |

1,650 |

1,098 |

67% |

January 2013 |

|

Cyclone Ita |

N/A |

8 |

N/A |

April 2014 |

|

Cyclone Marcia* |

750 |

544 |

73% |

February 2015 |

The second phase of research provided a preliminary cost-benefit analysis of implementing some of the existing engineering recommendations for reducing housing vulnerabilities identified in the first phase of research (Smith & Henderson 2015a). Drawing on this research, Suncorp released its Cyclone Resilience Benefit1 program in 2016. The product allows homeowners in cyclone-prone regions to receive up to 20 per cent reductions in insurance premiums based on the building features their home has that are known to reduce vulnerability in cyclones (e.g. window shutters).

Since the Queensland floods and Cyclone Yasi in 2011, there have been 11 separate inquiries into insurance affordability and preparedness for natural disasters (Table 2). The more significant of these include the Northern Australia Insurance Premiums Taskforce Report, the Productivity Commission Natural Disaster Funding Report, and three reviews by the Australian Government Actuary. The strong government focus on insurance affordability in recent times has further motivated the insurance industry to examine pragmatic solutions to address affordability concerns and continue offering insurance policies in high-risk natural hazard areas. Two common themes emerged from the inquiries:

The occurrence of disasters such as Cyclone Larry and Cyclone Yasi have led to higher claims cost, increased reinsurance costs, and subsequent increases to customer premiums. Increasing costs, coupled with the vulnerability of existing housing stock to cyclone risk, leaves Suncorp challenged in generating profitable growth. Suncorp’s approach to managing its exposure in cyclonic regions hinges on a concept known as ‘shared value’ (Porter & Kramer 2011), in which a company’s success and social progress are intertwined. Addressing issues of insurance premium affordability by reducing the vulnerability of the housing stock in north Queensland alleviates a societal problem. It also creates economic value for Suncorp and, therefore, a clear shared-value opportunity.

| Government Inquiry | Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

National Disaster Insurance Review |

November 2011 |

||

|

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal: In the Wake of Disasters Volume 1 and 2 |

February-March 2012 |

||

|

Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry |

March 2012 |

||

|

Australian Government Actuary: First Report on Investigation into Strata Title Insurance Price Rises in North Queensland |

October 2012 |

||

|

Productivity Commission Natural Disaster Funding Report |

May 2014 |

||

|

Australian Government Actuary: Second Report on Investigation into Strata Title Insurance Price Rises in North Queensland |

June 2014 |

||

|

Joint Select Committee on Northern Australia: Inquiry into the Development of Northern Australia: Final Report |

September 2014 |

||

|

Financial System Inquiry |

November 2014 |

||

|

Australian Government Actuary: Home and Contents Insurance Prices in North Queensland |

December 2014 |

||

|

Government response to the Senate report on recent trends in and preparedness for extreme weather events |

July 2015 |

||

|

Northern Australia Insurance Premiums Taskforce |

March 2016 |

Damage investigations carried out by the CTS following severe wind storms have typically shown that Australian houses built prior to the mid-1980s do not offer the same level of structural performance and protection during windstorms as houses constructed to contemporary building standards. The investigations also show that the majority of houses designed and constructed to current building regulations have performed well structurally by resisting wind loads and remaining intact (Boughton et al. 2011, Henderson et al. 2006, Reardon, Henderson & Ginger 1999). However, these reports also detail failures of these structures (Figure 2 and Figure 3) resulting from design and construction failings, poor water ingress protection, or degradation of construction elements (i.e. corroded screws, nails and straps, and decayed or insect-attacked timber).

The Suncorp and CTS collaboration commenced the research program by leveraging the CTS experience from damage investigations to examine Suncorp’s 25 000 claims following cyclones Larry and Yasi.. The aim was to develop a deeper understanding of factors that cause cyclone-induced losses. This was achieved by determining the relationship between physical damage modes identified in post-event field surveys and insured loss trends in the claims data. Some key findings from the study are:

In 2015, a second phase of research involved preliminary estimation of the cost-benefit ratio of several existing cyclone mitigation strategies in collaboration with economic consultant Urbis. The results compiled by Urbis are shown in Table 3.

| Mitigation option | Cost per household | Total benefit per household | Cost-benefit | Payback period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Community awareness campaign |

$55-$136 |

$440-$820 |

3.2-14.8 |

Less than 1-6 years |

|||||

|

Opening protection – self installed (low cost scenario) |

$1,660 |

$1,990-$6,400 |

1.2-3.9 |

4-21 years |

|||||

|

Roofing option – strapping only (low cost scenario)** |

$3,000 |

$12,900-$38,800 |

4.3-12.9 |

2-4 years |

|||||

|

Roofing option – over-batten system (medium cost scenario) |

$12,000 |

$13,500-$39,400 |

1.1-3.3 |

5-37 years |

In addition, the second phase of work explored the literature to understand homeowner behaviours and attitudes towards natural hazard risk and investing in mitigation (see Smith et al. 2016 for a detailed discussion). As discussed, a number of key psychological and situational barriers were identified. However, the decision-making process is often complicated and the key influences extend far beyond the homeowner. For example, Kunreuther, Meyer & Michel-Kerjan (2009) describe the ‘politician’s dilemma’, which refers to an elected official who often must weigh the choice between charging additional taxes for risk reduction measures with long-term benefits versus a potential loss in the next election.

The Cyclone Resilience Benefit (CRB) was released in early 2016 to address premium affordability issues in northern Australia. The CRB promotes risk mitigation by rewarding the efforts of homeowners who make their homes less vulnerable to cyclone damage through home improvements and cyclone preparation plans. Prior to the CRB, the cyclone component of the premium for a Suncorp home insurance policy generally considered the following attributes:

However, these criteria resulted in an incomplete view of a property’s vulnerability. The most important factor was the year of construction, as the cyclone component of the premium for a pre-1980s home could be up to three times that of a post-1980s property. There was no system capability for understanding work done to properties that would reduce the cyclone damage risk of pre-1980s properties (e.g. roof replacement, cyclone shutters, etc.), nor capability to recognise further mitigation work done on post-1980s properties. The CRB is a new rating system developed to better understand housing vulnerability and acknowledge the efforts of customers who invest in strengthening their home. In addition to the attributes considered, the CRB recognises upgrades to several aspects of the home including the roof, windows, doors, garage doors, sheds, as well as general preparedness (i.e. cyclone action plan).

The CRB is accessible to all Suncorp customers who live above the Tropic of Capricorn in Australia and the reduction amount varies between 1 per cent and 20 per cent of the property’s total premium. Since the CRB applies only to the cyclone and storm components of the premium, customers in higher cyclone risk areas receive larger reductions than those further from the coast and in southern latitudes. Properties that currently have higher premiums based on a relatively high level of structural vulnerability (e.g. pre-1980s), receive larger reductions than those with lower relative vulnerability (e.g. post-1980s) and therefore lower current premiums.

To determine the pricing rate for each mitigation upgrade, both the Suncorp and CTS research and expert judgement were used. Potential reductions to both the cyclone and storm peril components of the premium were included since improved performance of the property under cyclonic conditions reduces vulnerability during non-cyclonic storms (which are less severe in both intensity and duration). A reduction is not currently included for contents policies since the Suncorp and CTS research has primarily focused on the structure of the building envelope and less on loss from wind-driven rain.

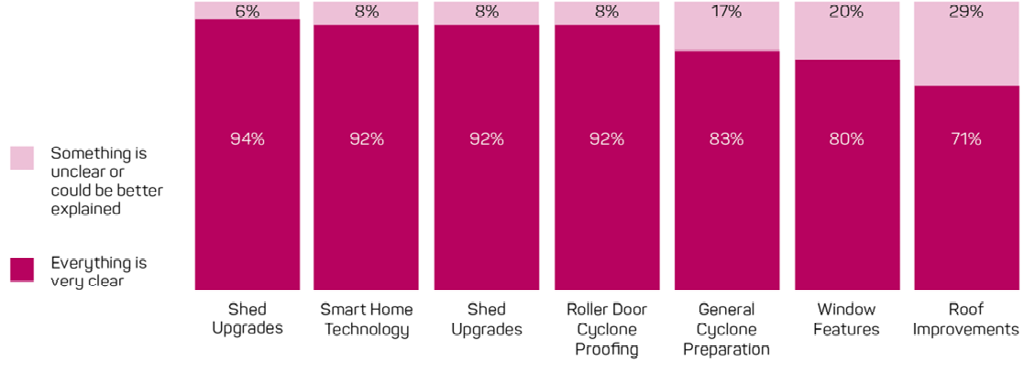

The primary link between Suncorp and homeowners interested in the CRB is a questionnaire regarding mitigation upgrades the home may have. In order to ensure details about the home are properly identified and communicated, it is important that the questionnaire is clear, concise and easy to follow. Each question is designed to elicit information about a particular type of housing vulnerability. Before releasing the CRB, Suncorp commissioned a customer survey to test the feasibility of the question set and received valuable feedback as a result. There were 65 surveys completed in total with all respondents living in either north Queensland (52 per cent), far north Queensland (43 per cent), or north-west Queensland (5 per cent). Each was a homeowner of the residence they currently live in. Figure 4 shows the results of survey in terms of homeowner understanding of the CRB rating questionnaire.

Key findings of the survey were:

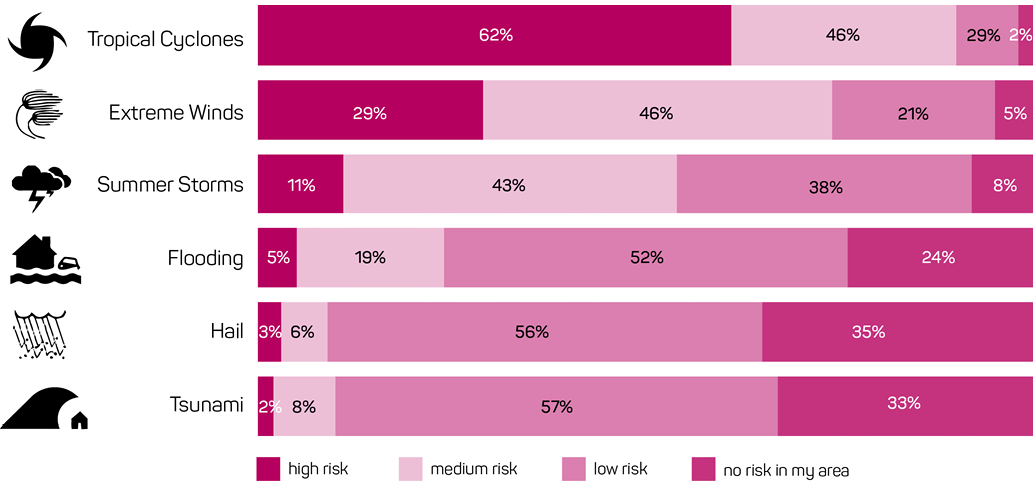

The questionnaire also asked customers about their perceived natural hazard threats for north Queensland (Figure 5). Over 90 per cent of respondents concluded that cyclones were a high or medium risk. This suggests that there is a significantly high level of risk awareness of natural hazards, likely due to the frequency of cyclonic events in the region and community outreach programs (e.g. ‘Get Ready Queensland’). However, risk awareness often does not translate into investment in mitigation by homeowners. A key aim of the CRB and the Suncorp and CTS collaboration is to promote mitigation investment by providing financial incentives via premium reductions.

The CRB received a positive response from the north Australian community. Over 14 000 homeowners have potentially received policy savings to date by answering the CRB questionnaire. The average premium reduction to date is approximately $100 annually. The collected CRB data will be continuously analysed to better understand housing vulnerability in the current building stock, homeowner attitudes towards mitigation, and how the CRB can be further enhanced.

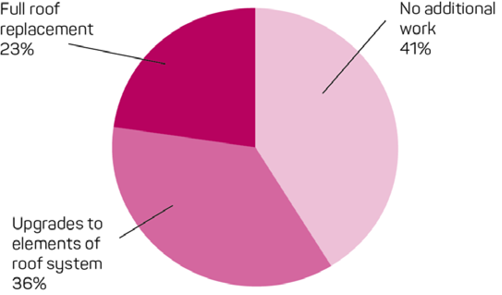

Of the pre-1980s homes, 41 per cent indicated that no additional upgrades had been completed for the roof structure to date (Figure 6). Although it is broadly accepted that these homes have a relatively higher level of structural vulnerability, roofing upgrades and replacements are expensive and the cost-benefit analysis case for homeowners is often not financially viable or not readily understood. While some upgrade solutions do exist (Standards Australia 1999a, b), they are often cost prohibitive or aesthetically displeasing. Although the average premium reduction for a full roof replacement is 16 per cent for pre-1980s homes, the cost is often in the order of $30,000 (Smith & Henderson, 2015a). Therefore, a key challenge in risk reduction for northern Australia is the innovation of more cost-effective retrofit options. However, even homes built to modern construction standards can have increased vulnerability due to corroded connections (e.g. roofing screws.) and deteriorated building materials. Savings for complete roof replacements may result in up to 10 per cent reductions for contemporary housing.

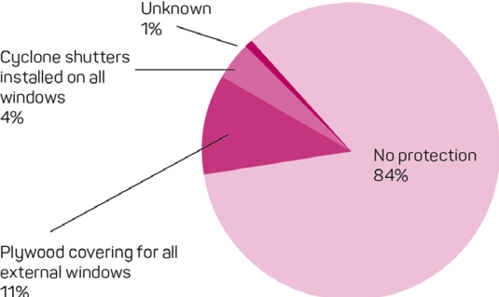

Figure 7 shows the proportions of CRB users with window protection. It is interesting to note that only 5 per cent of users have cyclone shutters. The use of shutters can significantly reduce the vulnerability of a structure by keeping the building envelope intact (i.e. reducing likelihood of internal pressurisation) and reducing the potential for water ingress. Depending on the house, shutter installation could be added for around $3,000.

Housing vulnerability to severe wind events in Australia has become a key societal issue as exposure increases due to population growth. The resultant losses are severe and have damaging impacts at a range of societal levels. Reducing vulnerability in the built environment is a difficult task that will require time, innovation and a concerted effort by stakeholders at all levels. The CRB represents a critical step forward by promoting risk-reflective pricing in the insurance industry that encourages investment in mitigation by homeowners. In March 2016, Suncorp, the Queensland Government and the CTS commenced a three-year research program in partnership with the University of Florida (Prevatt & Florig 2015, Smith et al. 2016, Smith et al. 2015c) to develop a cyclone mitigation tool known as ‘ResilientResidence’.2 In the immediate future, this research will:

This paper was supported by Suncorp, an Advance Queensland Research Fellowship, and the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC. The opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors, partners, or contributors.

Australian Government Treasury 2015, Northern Australia Insurance Premiums Taskforce Final Report Commonwealth of Australia, ACT, Australia.

Boughton GN, Henderson DJ, Ginger JD, Holmes JD, Walker GR, Leitch C, Somerville LR, Frye U, Jayasinghe NC & Kim P 2011, Tropical Cyclone Yasi Structural Damage to Buildings. Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University, Townsville. TR 57.

Harwood J, Paddam S, Pitman A & Egan J 2014, Can actuaries really afford to ignore climate change?, in: Proceedings of the Actuaries Institute General Insurance Seminar.

Henderson DJ, Ginger JD, Leitch C, Boughton G & Falck D 2006, Tropical Cyclone Larry – Damage to buildings in the Innisfail area. Cyclone Testing Station, James Cook University, Townsville. TR51.

Hutley N & Batchen A 2015, Protecting the North: The benefits of cyclone mitigation Urbis Pty Ltd.

Insurance Council Australia (ICA) 2014, Historical Disaster Statistics. Insurance Council Australia. At: www.insurancecouncil.com.au/industry-statistics-data/disaster-statistics/historical-disaster-statistic [11 September 2014].

Kunreuther H, Meyer R & Michel-Kerjan E 2009, Overcoming Decision Biases to Reduce Losses from Natural Catastrophes Risk Management and Decision Processes Center, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Porter M & Kramer M 2011, Creating Shared Value, Harvard Business Review.

Prevatt DO & Florig K 2015, Effectiveness of a smartphone-based decision support system to stimulate hurricane damage mitigation actions among homeowners in Coastal Hillsborough County, Florida communities. Florida Sea Grant University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Reardon G, Henderson D & Ginger J 1999, A structural assessment of the effects of Cyclone Vance on houses in Exmouth, WA Cyclone Testing Station 1999, James Cook University, Townsville. TR 48.

Smith DJ & Henderson DJ 2015a, Cyclone Resilience Research – Phase 2. CTS Technical Report TS 1018.

Smith DJ & Henderson DJ 2015b, Insurance claims data analysis for cyclones Yasi and Larry. CTS Technical Report TS 1004.2.

Smith DJ, Roueche DB, Thompson AP & Prevatt DO 2015c,A vulnerability assessment tool for residential structures and extreme wind events, Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Performance-based and Life-cycle Structural Engineering. School of Civil Engineering, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, pp. 1164-1171.

Smith DJ, Henderson DJ & Ginger JD 2015a, Improving the wind resistance of Australian legacy housing, in: Proceedings of the 17th Australasian Wind Engineering Society Workshop.

Smith DJ, Henderson DJ & Ginger JD 2015b, Insurance loss drivers and mitigation for Australian housing in severe wind events 14th International Conference on Wind Engineering, Porto Alegre, Brazil, June 21-26.

Smith DJ, McShane C, Swinbourne A & Henderson DJ 2016, Toward effective mitigation strategies for severe wind events. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol, 31, no. 3, pp. 33-39.

Standards Australia 1999a, HB132.1 Structural upgrading of older houses, Part 1: Non-cyclonic areas Standards Australia, Sydney, NSW.

Standards Australia 1999b, HB132.2 Structural upgrading of older houses, Part 2: Cyclonic areas Standards Australia, Sydney, NSW.

Swiss Re 2016, Natural catastrophes and man-made disasters in 2015: Asia suffers substantial losses, Sigma.

Jon Harwood is the Product Solutions Manager with Suncorp Group Limited.

Dr Daniel Smith is a research fellow with the Cyclone Testing Station.

Dr David Henderson is Director of the Cyclone Testing Station investigating effects of wind loads on low-rise buildings.

1 Cyclone Resilience Benefit program. At: www.suncorp.com.au/insurance/safety/cyclone-resilience.

2 ResilientResidence. At: www.resilientresidence.com