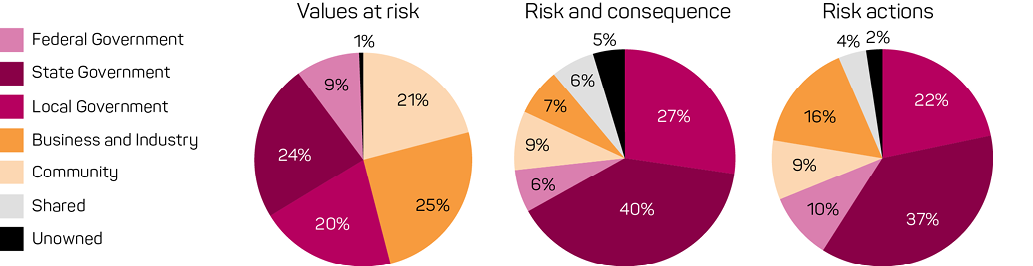

Four workshops held in 2015 investigated values, risk and consequences, actions and ownership for strategic risk management linked to prevention, preparedness and recovery. Building on a foundation of values at risk – social, economic, environment and built infrastructure – ownership of these values was linked to ownership in designated areas of strategic risk management. For values at risk, patterns of ownership at the institutional scale showed relatively even balance, but when risks, consequences and actions were surveyed, they became skewed towards two areas of government: state and local. Further work is needed to determine how these patterns of ownership can be more evenly distributed to achieve more sustainable outcomes.

In 2012, the US National Academies declared ‘disaster resilience is everyone’s business and is a shared responsibility among citizens, the private sector, and government’ (National Academies 2012). This is reflected in Australia, where the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience states ‘disaster resilience is the collective responsibility of all sectors of society, including all levels of government, business, the non-government sector and individuals’ (COAG 2011).

There is broad agreement that investment in prevention and preparedness provides significant returns on investment in avoided damage, and that planned recovery can minimise unavoidable damage and subsequent loss (Deloitte Access Economics 2013, Kelman 2013, Hallegatte 2015). However, Australia’s capacity to be disaster resilient in this respect is limited by a lack of investment and limited connectivity between the major institutions concerned.

For the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC project ‘Mapping and understanding bushfire and natural hazard vulnerability and risks at the institutional scale’, interpretation of the above implies a shared capacity for the ownership of natural hazard risks (i.e. risk ownership). Risk ownership is identified as a key attribute of resilience at the institutional scale (Jones, Young & Symons 2015a, 2015b, Young, Symons & Jones 2015a, 2015b). The 2015 workshops and desktop assessments examined risk ownership of natural hazards from a decision-making perspective.

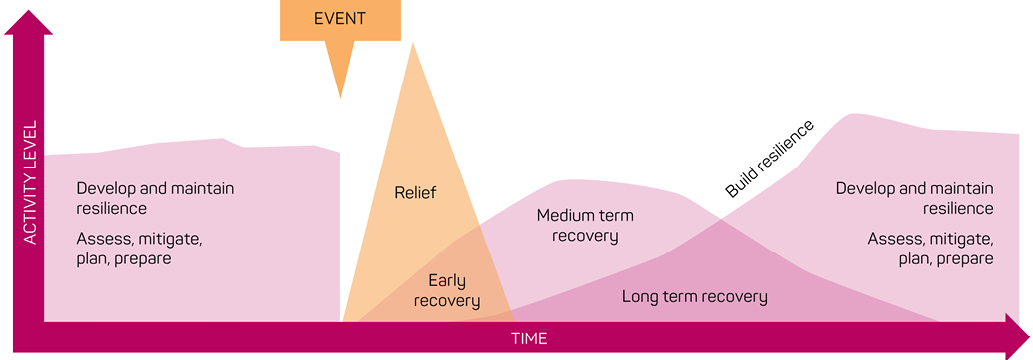

The area of focus in this paper is strategic risk concerning prevention and preparedness before events, and recovery after events. Omitted is the response phase during events.

This work is based on the following propositions:

Assessing risk ownership at the institutional scale was undertaken using the following core components:

Two major questions for the four workshops undertaken in Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia were:

A total of 118 participants from government, boundary organisations and business and industry attended the workshops. The workshops used a scenario-based approach concentrating on fire, flood and heatwave. The following exercises were used during the workshops.

Exercise 1: Establishing understanding

Presentations provided an overview of the research undertaken to date, followed by a group discussion.

Exercise 2: Ascertaining values at risk

Participants were asked to map the social, environmental, built environment and economic values likely to be affected by the scenario event. Participants mapped dependencies being one-way (supporting dependency) and two-way (mutual dependency). They also listed the institutional owners of those values and selected what they considered the most significant value for the next exercise.

Exercise 3: Mapping risks to values and owners

Using the nominated value, participants listed the consequences of their hazard scenario across social, economic, environmental and built infrastructure areas. They allocated the resulting risks and consequences to short-, medium- and long-term timeframes. Finally, they were asked to allocate owners for the identified risks.

Exercise 4: Mapping owners of risk actions

Participants were asked to list actions that could be undertaken in the short- and long-term to mitigate the risks identified in the mapping stage of the exercise. In Victoria, participants were asked to allocate ownership in these areas according to RAP criteria (who is Responsible, who is Accountable, and who Pays).

Exercise 5: Needs, barriers and opportunities

Each group was asked to identify needs, barriers and opportunities and consolidate key themes from the workshop.

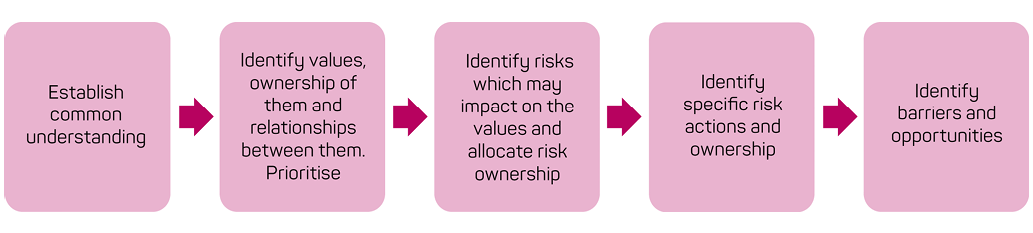

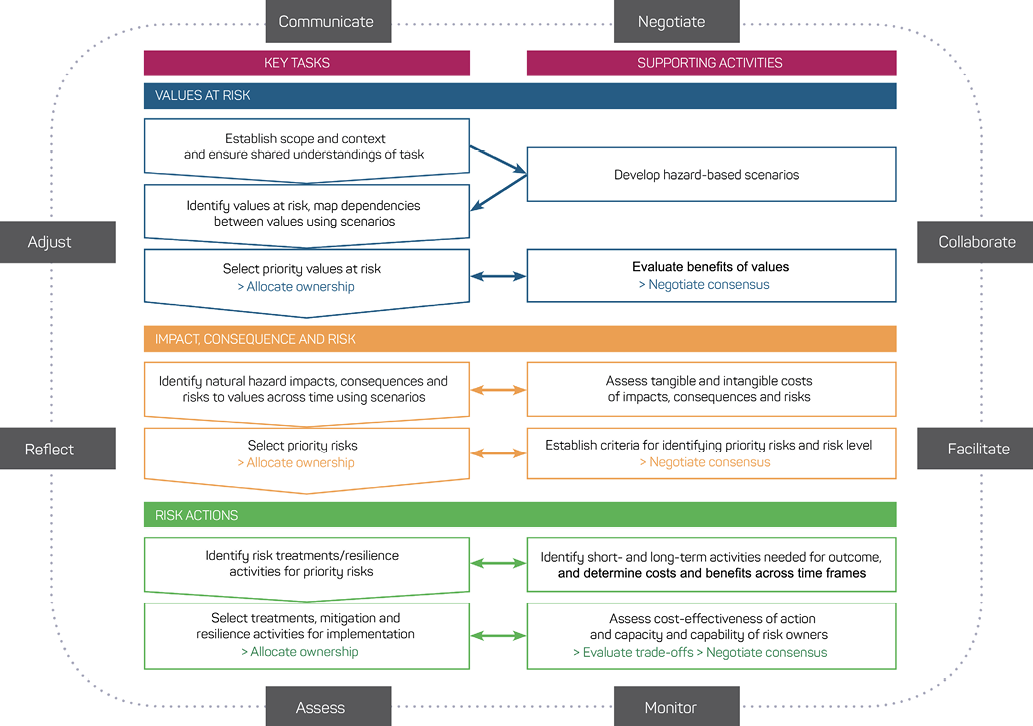

The key components of the workshop process are shown in Figure 2.

All responses were recorded on templates that were later transcribed and collated. A mixture of basic statistical methods and analysis was used to synthesis the data with the detailed results presented in a workshop report (Young, Jones & Symons 2016a).

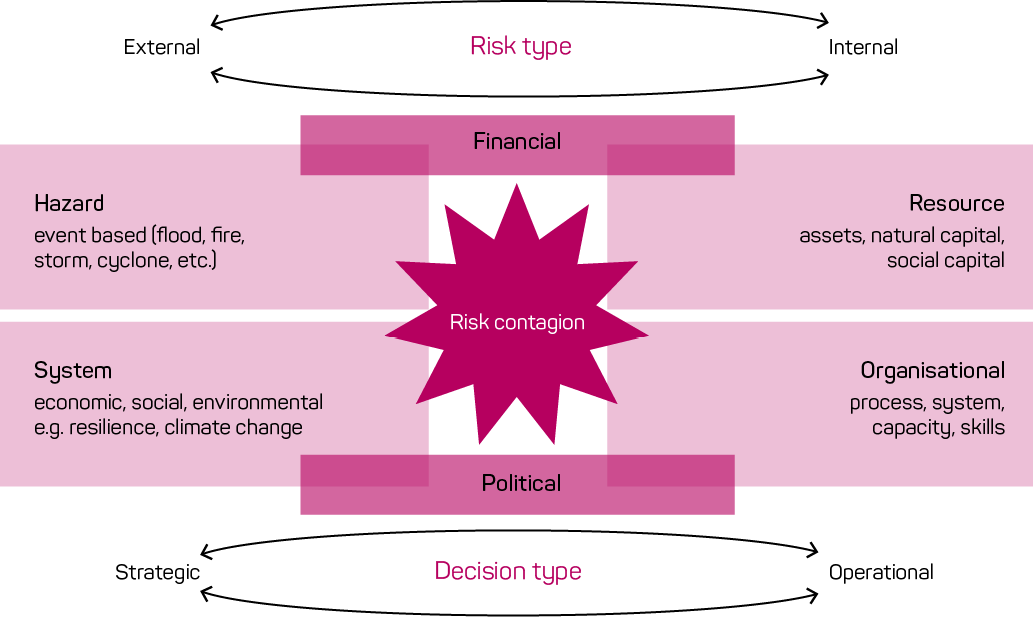

Natural hazard risk is systemic, and risk ownership needs to be understood within that context. Natural hazards are externally generated but the condition of the system they impact on greatly affects the level of subsequent damage. Both externally and internally generated risks can interact, producing consequences that resonate well beyond the direct effects of a specific hazard event.

It is important to understand how the different types of risk and their interactions with a system affect an institution, organisation, or community (Figure 3). It is also important to understand which forms of governance are suited to the nature of a particular risk and its context.

Internally based risks are more likely to have limited impacts within a defined system and are more amenable to controls by risk owners. The effectiveness of these controls often determines the ability of institutions, organisations and communities to manage effects of externally driven risks. Effective management of these internally driven risks is a key part of building organisational resilience and the ability to proactively respond rather than react to an event with simple damage control.

Externally based risks are often beyond the control of any single institution. They are usually systemic and highly dynamic and can have multiple owners. The boundaries of these risks are often unclear, spanning multiple areas (both geographic and institutional) and timeframes. They can be prepared for, but not predicted, and because of the high level of uncertainty regarding the future, often have unanticipated outcomes.

The strategic management of natural hazard risk also needs to account for political and financial risk. The internal aspects of these risks will influence perceptions and decision-making at an individual scale, as well as at institutional scales. External risks arise from external policy and financial markets that can influence the level of risk different parties are exposed to.

Institutions, organisations and communities may own their internal risks but may not have explicitly taken ownership of natural hazard risks or contemplated the full impact of those risks on their values and goals.

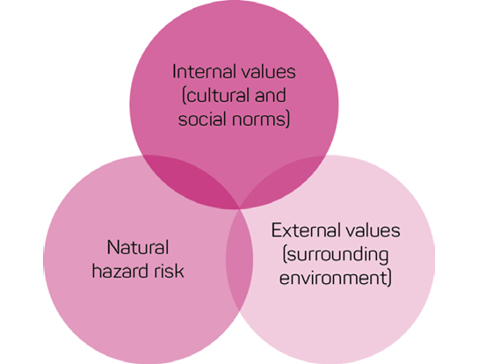

The values associated with these risks are also systemic and have a significant influence on decision-making (Figure 4). Although this project focused primarily on the interaction between the external and natural hazard risk, the role of internal values is still a major consideration in terms of what decisions are made and how they are made.

What values are important to an organisation and the risks associated with them will determine the types of decision-making to be used. It also defines who needs to be involved, the thinking frameworks, and the leadership needed to effectively manage the risk (Table 1).

| Type of decision | Simple | Complicated | Complex |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Characteristics |

Linear, actionable, can be solved with one solution. Often static risks with known treatments and outcomes. |

Systemic, can be bounded but may require more than one solution to address. Will use a mixture of known and unknown treatments. Dynamic, but usually able to be stabilised over time. |

Systemic, unbounded, multiple interrelated actions and solutions required to address the issue. The treatment will often evolve and change over time. Highly dynamic and unpredictable, high levels of uncertainty. Often high-impact low probability. |

|

Example |

A faulty piece of machinery. |

Containment of a natural hazard event. |

Climate change, resilience. |

|

Actors |

Individual to organisational: person(s) with allocated responsibility or the asset owner. |

Collaborative: parties associated with, and effected by, the event. Shared ownership with delegated areas of responsibility. |

Extensive collaboration: a ‘whole-of-society approach’. Complex collaborative ownership that is shared across all areas of society. |

|

Thinking frameworks |

Logical, analytical, prescriptive and practical. |

Short- to medium-term thinking, analytical, responsive. Predominantly prescriptive, but has intuitive elements that respond to changing circumstances. |

Long-term, strategic, conceptual, lateral, analytical, creative, reflexive, continuous, flexible. |

|

Leadership actions |

Direct and review. |

Consult, assess, respond and direct. |

Consult, facilitate, empower and direct. |

Risk ownership is dynamic, having two senses as illustrated by the following definitions (Young et al. 2015):

Exposed to natural hazards, risk ownership can change abruptly. Two of the key ways this can happen are as a result of:

‘Risk contagion’ is a term most commonly used in relation to financial risk. It describes how financial shocks travel through an economic system and can ‘infect’ other areas of the economy. Impacts are seen to spread across geographical and institutional borders ‘like a contagious disease’ (Bordo & Murshid 2001), creating a cumulative effect far larger than the initial event. This type of systemic understanding of risk is well understood in the natural hazard literature through catastrophe risk (Hewitt & Burton 1971, Burton, Kates & White 1993) in areas of social and environmental systems. However, the idea of risk contagion has recently emerged in business models as a way to understand how different areas of risk can be affected by seemingly unrelated risks. This is particularly relevant to the natural hazard sector where risk ownership may be allocated for direct impacts, but not for indirect knock-on effects (e.g. Hallegatte 2015).

Another aspect associated with changing risk ownership is the breaching of capacity thresholds (environmental, social or economic; Jones et al. 2013) where the original risk owner will transfer the responsibility of the risk to another owner (either by a prior arrangement or by default) because they lack the capacity to address or manage the risk.

In terms of risk ownership, identifying whether the nature of the risk is changing through contagion or capacity exceedance is important as this determines how the ownership may be transferred or where risks may become ‘unowned’. It can also help identify potential areas of vulnerability and support better long-term management of these risks.

The workshops explored the role of values and risk ownership in strategic decision-making in the emergency management sector. They highlighted the complexity and the challenges of making value-based strategic decisions in relation to natural hazards and the cultural, political and organisational barriers faced by different organisations.

Across all workshops, 330 values were identified and 621 risk ownership allocations were made to these values, 403 risks and consequences were identified, with 172 ownership allocations made. For actions, 191 were identified and 204 allocations made across the workshops in NSW, South Australia and Tasmania. In the Victorian workshop, 91 ownership allocations were made using the RAP criteria.

Specific activities across 12 identified risk areas identified during the workshops show the current diversity in state-based approaches, contexts and levels of maturity related to strategic thinking, risk ownership and resilience. They also raised some of the challenges facing the emergency management sector in establishing a common understanding of natural hazards and their strategic management. The ownership exercise in the Victorian workshop using the RAP criteria was particularly contentious.

The collated results of the value, risk and consequence, actions ownership mapping exercises are shown in Figure 5. Ownership of values at risk are fairly evenly distributed across the various institutions, but this changes as the focus moves to risks and consequences, where the role of local and state governments increases and business and industry and the community decreases. For actions, some balance is re-established, but state government still retains the largest share of ownership.

The allocation of ownership to delegated risk managers showed an increase in government responsibility and an increase is shared and unowned risks. This is perhaps counter to the ‘everyone’s business’ and ‘shared responsibility’ sentiments national strategies and suggests directions for further research. In particular, there is a need to clarify if these findings reflect the real levels of private and public sector ownership and what balance of public and private ownership is sustainable and can best support community resilience. Further research to clarify how ownership is shared between institutions, to identify unowned risks, and to understand how ownership can be most effectively delegated is needed.

The workshops produced a number of common themes relating to needs, barriers and opportunities. The most common themes raised concerns about limitations of current decision-making structures, approaches, systems and tools, in particular, the inability of these to meet the emerging needs of communities, government and non-government organisations trying to implement resilience and recovery. Exploring ownership in greater detail can help address these needs.

In summary, key findings were:

New decision-making arrangements are needed if communities and the private sector are to be actively involved in building resilience. These needs are already driving policy and social innovation. Inclusive approaches that really engage communities as part of the decision-making process are being developed. Current activities identified in these areas are the ‘Safer Together Community First’ policy (Victorian Government) and the ‘Bushfire Ready’ neighbourhoods program (Tasmanian Fire Services). ‘Safer Together Community First’ is a policy framework for inclusive decision-making between communities and government. The ‘Bushfire Ready’ neighbourhoods program works from a strong evidence base and focuses on engagement with communities to build understanding and acceptance of risk so that communities feel empowered to act and are responsible for their own risks.

Changes in organisational cultures, longer-term strategic development and resource allocation have been important for these innovations. There is a need to rethink current expectations in these areas across the emergency management sector to support further innovation.

The strategic risk management of natural hazard risks is built on a foundation of values at risk covering economic, social, environmental and built infrastructure values, rather than the specific hazards (e.g. fire, flood). This allows the ownership of key values to be linked with the ownership of actions intended to benefit those values at risk.

The use of values as the basis of the decision-making process places the focus on what is most important. It can help address both long- and short-term aims and goals across public and private institutions. Identifying what values have priority over a range of timescales provides a foundation for long-term planning.

This can also help communities to develop strategies that take ownership of the values most important to them and what their responsibilities are in relation to this. However, institutional arrangements between different actors will be needed to manage shared risk and changing ownership that manages risk contagion and capacity limits. As risk ownership is a ‘negotiated process’ (Young, Jones & Symons 2016a) this process is not without challenges. It requires collaboration and meaningful engagement to achieve fruitful outcomes. It is a long-term proposition that involves multiple parties and requires the development of fit-for-purpose frameworks.

Key components and questions for the values-based decision-making process framework currently in development as part this project are described in Figure 6.

Risk ownership of natural hazards has traditionally been focused in the area of effective response, administered primarily through command-and-control mechanisms. However, the changing nature of natural hazards and the socio-economic context in which they occur is leading to the emergence of new and different types of risks. The need for community, businesses and government to build greater resilience to these risks requires a strategic focus that goes beyond the event and builds greater capacity in all areas of our society.

Effective long-term planning, preparedness and recovery requires:

The workshops explored preferences concerning values and risk ownership in strategic decision-making. They identified cultural, political and organisational barriers facing people in different public and private organisations in relation to these areas. More importantly, they highlight the opportunity to transform how society thinks about and responds to natural hazards. They point to a need for greater understanding of what the risks are and who owns them across different areas of society. Targeted resources, community engagement, long-term policy and investment and re-alignment of current expectations that match current capacities and capabilities across both the public and private sectors are needed if these challenges are to be overcome.

At the heart of risk ownership are communities and businesses, and the need for common understandings and collaboration between them and the public sectors. Strategic decision-making based on values and ownership of risks provides the bridge between the present and the future; one that can help decisive action and collaboration in the present, while thinking and planning ahead. It is a crucial factor for preparedness and effective response to natural hazards now and in the future.

This research is supported by funding from the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC.

Australian Emergency Management Institute (AEMI) 2011, Community recovery. Australian Emergency Management Handbook Series, Handbook 2. Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra, ACT.

Australian Emergency Management Institute (AEMI) 2014, National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines. Australian Emergency Management Handbook Series, Handbook 10. Attorney-General’s Department

Bardo MD & Murshid AP 2001, Are financial crises becoming more contagious? What is the historical evidence on contagion? In: Claessens S, Forbes KJ (eds) International financial contagion. Springer, New York, pp. 367-403.

Burton I, Kates RW & White GF 1993, The environment as hazard. Guilford Press, New York, NY, USA.

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: building our nation’s resilience to disasters. Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra, ACT.

Deloitte Access Economics 2013, Building our nation’s resilience to natural disasters. Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities, Deloitte Access Economics, Barton, ACT.

Department Land, Water, Environment and Planning, Victorian Government, Safer Together, Community First webpage. At: www.delwp.vic.gov.au/safer-together/community-first [10 June 2016].

Haraguchi Mn & Lall U 2015, Flood risks and impacts: A case study of thailand’s floods in 2011 and research questions for supply chain decision making. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 14, pp 266-272..

Hallegatte S 2015, The indirect cost of natural disasters and an economic definition of macroeconomic resilience. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (7357).

Hewitt & Burton I 1971, The hazardousness of a place: A regional ecology of damaging events. University of Toronto, Toronto.

ISO 2009, ISO 31000:2009 risk management - principles and guidelines. International Organisation for Standardisation, Geneva.

Kambil A, Layton M & Funston R 2005, Disarming the value killers. StrategicRISK June 2005, pp. 10-33.

Kelman I 2013, Disaster mitigation is cost effective. Briefing Note, World Development Report 2014.

Jones RN, Young CK, Handmer J, Keating A, Mekala GD & Sheehan P 2013, Valuing Adaptation under Rapid Change. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Queensland.

Jones RN, Patwardhan A, Cohen S, Dessai S, Lammel A, Lempert R, Mirza, MMQ & von Storch H 2014, Foundations for decision making. In: Field CB, Barros V, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy A, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR & White LL (eds). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability Volume I: Global and Sectoral Aspects Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 195-228.

Jones RN, Young C & Symons J 2015a, Mapping Values at Risk from Natural Hazards at Geographic and Institutional Scales: Framework Development, Victoria Institute of Strategic Economic Studies (VISES), Victoria University and Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria.

Jones RN, Young C & Symons J 2015b, Risk ownership and natural hazards: Across systems and across values. Paper presented at the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC and AFAC annual conference 2015, Adelaide, South Australia.

Jones RN, Young CK, Handmer J, Keating A, Mekala & Sheehan P 2013, Valuing adaptation under rapid change. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility, Gold Coast, Queensland.

National Academies 2012, Disaster resilience: A national imperative. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

North DC 1990, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC) 2013, Black swans turn grey: The transformation of risk. PricewaterhouseCoopers Limited, Hong Kong.

Productivity Commission 2014, Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements, Draft Inquiry Report: Canberra.

State Emergency Service 2015, State emergency management plan, version 2.15. Government of South Australia, Adelaide.

Tasmanian Fire Services 2015, Bushfire Ready Neighbourhoods. At: www.bushfirereadyneighbourhoods.tas.gov.au/ [10 June 2016].

Young C, Jones RN & Symons J 2015a, Understanding our values at risk and risk ownership workshop context paper. Victoria Institute of Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University, Melbourne, Victoria.

Young CK, Symons J & Jones RN 2015b, Whose risk is it anyway? Desktop review of institutional ownership of risk associated with natural hazards and disasters. Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria.

Young CK, Jones RN & Symons J 2016a, Understanding Values at Risk and Risk Ownership Workshop Synthesis Report, Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria.

Young CK, Jones RN & Symons J 2016b, Institutional Maps of Risk Ownership for Strategic Decision Making, Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC, Melbourne, Victoria.

Young OR, King LA & Schroeder H 2008, Institutions and Environmental Change: Principal Findings, Applications, and Research Frontiers. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Celeste Young is a Collaborative Research Fellow at the Victoria Institute of Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University. Her key areas of focus are developing frameworks and methods for using and implementing research in decision-making, understanding risk, innovation and stakeholder engagement. She has developed a number of successful frameworks and programs that are used in areas of climate change adaptation and was a contributing author to the Foundations of Decision Making chapter in the latest IPCC report.

Roger N. Jones is a Professorial Research Fellow at the Victoria Institute of Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University. He works on understanding and managing climate change risk, natural hazard risk and the ecological economics of urban systems. He was a lead author on chapters assessing risk and decision making in the last three IPCC reports.

1 A boundary organisation is a bridging institution, social arrangement, or network that acts as an intermediary between different interest groups. Its functions include communication between researchers and stakeholders, translating science and technical information, and mediating between different views of how to interpret that information (Jones et al. 2014).