Australia has a long history of flooding, with many towns, cities, and roads at risk of inundation. Flooding is a result of a variable climate of dry spells and flooding rains. Floods can vary in speed of onset from minutes to weeks. Flooding has also been identified as Australia’s second most deadly natural hazard with Australia’s extreme heat being the deadliest (Coates et al. 2014b). Recent flood events in Australia illustrate the dangers of flooding—in particular, those associated with motorists deliberately entering floodwater (Coates et al. 2014a).

Floodwaters can submerge vehicles, or sweep them away. As little as 30cm of still floodwater is sufficient to float a small passenger vehicle, and 50cm for a 4WD (Shand et al. 2011). Moreover, drivers may be unable to see what lies beneath flood waters. Large sections of roads often deteriorate or wash away. Significant velocities are also associated with flash flooding. Such events are considered more dangerous to motorists and passengers (Terti et al. 2015).

People entering floodwaters by vehicle constitutes a major cause of flood fatalities in Australia and globally (Ashley & Ashley 2008, Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2015, FitzGerald et al. 2010, Jonkman & Vrijling 2008, Jonkman & Kelman 2005, Sharif et al. 2012, Sharif & Chaturvedi 2015, Terti et al. 2015, Yale et al. 2003). Over the 20 years to 2014, the PerilAUS database, maintained by Risk Frontiers, shows that 81 people have died in Australia attempting to drive through floodwaters. These comprise 43 per cent of all flood fatalities over this period. The data shows that 35 per cent of these people were driving 4WDs (Gissing et al. 2015). In a similar study by FitzGerald and colleagues (2010), 48.5 per cent of flood deaths in Australia were found to be vehicle-related.

Not surprisingly, a large percentage of flood rescues performed by emergency services agencies are also of people from vehicles. Haynes and co-authors (2009) analysed flood rescues performed during the Hunter Valley floods of June 2007 and found that 36 per cent of rescues had been from vehicles. These rescues inherently put emergency services personnel at high risk.

In the United States, Ashley and Ashley (2008) found that 63 per cent of fatalities during a flood occurred in vehicles. Similarly Špitalar and co-authors (2014) found that 68 per cent of flash flood fatalities were vehicle-related. Jonkman and Vrijling (2008), in a review of flood deaths across Europe and the United States, identified that 32 per cent of deaths were associated with vehicles; the most significant of all flood fatality causes. In Greece, vehicle-related deaths were identified as the most common cause, constituting approximately 40 per cent of all flood fatalities (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2015).

International research indicates that motorists drown through a variety of ways:

Vehicles can be deliberately driven into floodwaters, can enter floodwater unexpectedly (Yale et al. 2003), or be parked and suddenly surrounded by floodwater (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013). However, motorists often deliberately enter floodwaters to reach a destination (Coates 1999, Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013), to rescue someone, to recover something (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013), or to evacuate (Becker, McClure & Davis 2011).

Explanations for motorists deliberately entering floodwaters include people:

Motorists may develop a false sense of security from being inside a vehicle (Jonkman & Kelman 2005, Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013, Maples & Tiefenbacher 2009). It is also possible that motorists may struggle to appreciate flood conditions, such as the depth and speed of floodwaters and the influence such conditions may have on vehicle stability (Yale et al. 2003, Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013). It is also suggested that drivers may recognise the risk but fail to personalise it, believing that the risk does not apply to themselves, therefore demonstrating ‘optimism bias’ (Pearson & Hamilton 2014).

Ruin, Gaillard and Lutoff (2007) concluded that drivers with the longest routes to travel and those with no prior flash flood experience were most likely to underestimate the level of risk associated with entering floodwater in a vehicle. However, previous flood experience has also been associated with a greater likelihood of drivers entering floodwater (Pearson & Hamilton 2014).

The time of day has been identified as a possible contributor to this risk-taking. Analysis of vehicle-related fatalities in Greece and the United States show that most fatalities occurred at night (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013, Špitalar et al. 2014, Maples & Tiefenbacher 2009) when motorists were unable to see flooded roadways. They may therefore enter floodwater by accident (Špitalar et al. 2014) or are unable to judge the depth and speed of water due to poor visibility (Maples & Tiefenbacher 2009). Alcohol and drugs may also have an influence (Jonkman & Kelman 2005), as well as social pressures caused by passengers within the vehicle (Pearson & Hamilton 2014).

Analysis of demographic trends relating to fatalities in the United States reveals that the majority of motorist flood deaths are by people aged 20 to 69 years (Kellar & Schmidlin 2012), while Diakakis and Deligiannakis (2013), in their analysis of data from Greece, found most victims were aged 40 to 69 years. However, Drobot, Benight & Gruntfest (2007) found that younger drivers (18-35 years) were more likely to indicate that they would be willing to drive into floodwater.

Males are overrepresented in motorist flood death statistics (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013, Kellar & Schmidlin 2012, Jonkman & Kelman 2005, Drobot, Benight & Gruntfest 2007, Sharif et al. 2012, Maples & Tiefenbacher 2009). Franklin and colleagues (2014) found that more males enter floodwater in vehicles than females. This higher rate of male deaths has been attributed to the risk-taking behaviour of males generally (Jonkman & Kelman 2005).

Vehicle-related flood deaths are avoidable. Despite Australian emergency services agencies mounting campaigns such as the FloodSafe program1 and urging people not to enter floodwater, the behaviour persists. There is scant research into the influence of road signage and barricades on driver behaviour, despite some research recommending steps be taken to improve road signage (Diakakis & Deligiannakis 2013). Fieldwork conducted during this study helps identify the effectiveness of road closure barricades in influencing motorist’s behaviour and provides insights into the effectiveness of community engagement campaigns and flood warnings.

Flooding around the Shoalhaven River, NSW, on 26 August 2015, provided the opportunity to observe the decision-making of motorists posed with the choice of whether or not to enter floodwaters. In the months and years before the flooding, the NSW State Emergency Service had undertaken community engagement programs with the key message to motorists not to enter floodwaters. During the flood, warning messages were released via broadcast media, websites and social media with messaging not to enter floodwaters. Road closure barricades were erected near flooded road sections to close roads and to dissuade motorists from travelling along them.

The research team were located near a ‘road closed’ sign that blocked passage along a flooded road north of the township of Nowra. The road is typically used as a back road by local traffic between the major highway and an industrial estate. The road was closed in both directions, but road-closed barricades were erected on one side of the road only, allowing access along the opposite side. The floodwater depths over the road were estimated to range from 10 to 30cm over approximately 50 metres with water flowing slowly. An alternate flood-free route was available for motorists to use, though it is not known if motorists were aware of its existence.

Image: Andrew Gissing

Researchers used an observation place near a ‘road closed’ sign in the town.

Over the course of nearly two hours during afternoon daylight hours, decision-making of drivers was recorded according to the number of vehicles entering floodwater, the type of vehicle, and the gender of the driver. More general observations were also made about the behaviour of motorists, the number of passengers in vehicles and an estimate of the age of drivers. From the observation site, vehicles were recorded travelling in both directions, but it was not possible to record the gender of the driver in all instances due to tinted vehicle windows, rainy conditions, and the speed at which vehicles passed. Vehicle types recorded were based on observations of the size and shape of the vehicles observed rather than a typology of vehicle manufacturers and models.

Image: Andrew Gissing

The research location included a local road closed by floodwaters. There were no depth markers or side railings along the section of flooded road.

Observations were recorded of 154 motorists in total. Of these, 84 per cent of drivers chose to ignore road closure signs and drove through the floodwater. Some motorists were influenced by the behaviour of other drivers, only proceeding through the floodwater after another vehicle had already entered. Similar behaviour was observed in respect to motorists turning around, with other motorists turning back after the initial driver had done so.

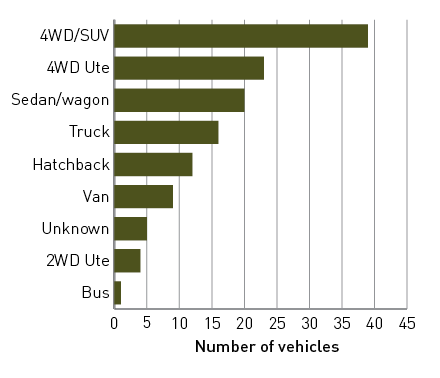

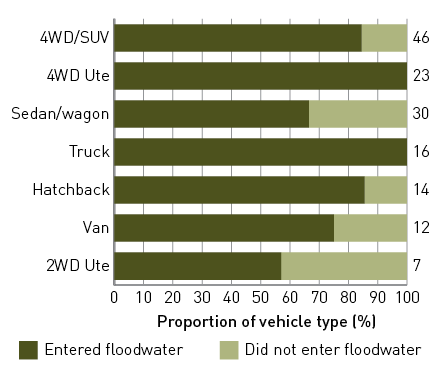

The types of vehicles driven through the floodwater varied in size and type as shown in Figure 1, though 4WDs and SUVs were the most frequent (48 per cent). Of those vehicles that turned around, two-wheel-drive utilities and sedans and station wagons were the most frequent vehicle types, as shown in Figure 2.

Notes:

1. Numbers at right describe the number of vehicles in each category

2. 1 bus and 5 unknown vehicles are not shown

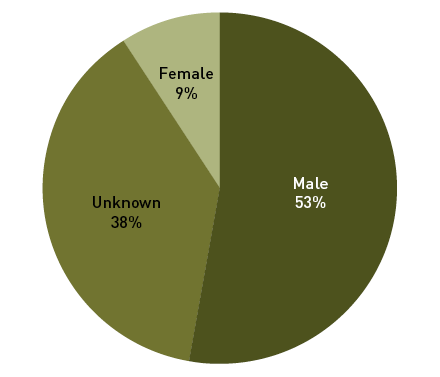

The vast majority of drivers who drove into the floodwater where gender could be determined were male. Figure 3 shows the breakdown by gender.

The age of the drivers varied significantly. All age groups were observed entering floodwater. The number of passengers in the vehicle also varied from zero to a school bus full of children. Vehicles from some local and government agencies were also driven through the floodwater, as well as two P-plate and one L-plate restricted license drivers. A few drivers also drove through the floodwater, simply to turn around and drive back through the floodwater again.

This research shows that, on the whole, motorists ignored road-closed signage. It suggests that motorists:

Further work is clearly needed to reduce the frequency of motorists entering floodwater and requires the development of a holistic approach comprising of a continuum of measures including education, regulation and engineering measures (Gissing et al. 2015).

This research highlights the limitations of ‘road closed’ signage to influence driver behaviour. In this example, the use of a single lane barricade was clearly ineffective. The erection of barricades aims to dissuade motorists from entering floodwater. Due to the portable nature of barricades, motorists are able to move them or possibly drive around them. Flooding may also occur before authorities can establish barriers. In this case study the effectiveness in dissuading motorists to proceed past the closure could have been higher if barricades blocked access across the full width of the road, or if the barricades had been manned by emergency services personnel. The ability to deploy barricades is also dependent on the availability of sufficient flood warning time, the number of signs available, and the human resources to do so.

Similar research in the context of warning signage at railway crossings has revealed that passive warning signs have low rates of compliance. Motorists continue to cross railway lines. Higher rates of compliance resulting in motorists stopping are achieved by more active systems involving flashing lights and boom gates (Tey, Ferreira & Wallace 2011). Further research could examine how signage and barricades could be improved to assist in modifying motorist behaviours.

This fieldwork also suggests the limited reach and effectiveness of community education and warning messages not to enter floodwater that have been the primary approach used by emergency services organisations. The ‘Turn Around Don’t Drown’ campaign2 has run in the United States for some ten years and is internationally recognised. However, evaluation of campaigns has been limited. To be successful the campaigns must use messages and communication channels that target risk groups (in particular males) and involve multiple partner agencies, not just the emergency services. Partner agencies include road safety groups, peak motorist groups, water safety bodies, insurance companies and schools. Perhaps car manufacturers could be dissuaded from showing advertising imagery that may encourage drivers to enter floodwater (Gissing 2015).

Source: www.nws.noaa.gov/os/water/tadd

US National Weather Service ‘Turn around don’t drown’ road sign.

Several emergency service vehicles entered the floodwater without any observed emergency reason and without sirens or warning beacons activated. Work is also needed to educate workers from government agencies about the importance of not driving through floodwater. A discussion with a National Roads and Motorists’ Association (NRMA) roadside assistance driver about driver decision-making was held during the field work. The driver had turned around and taken the alternative route. The driver said that the NRMA was a peak motoring body that advocated safety and that driving through floodwater would send the wrong message to other motorists. As the research indicated, motorist behaviour – whether to enter floodwater or to avoid it – is influenced by viewing other motorist actions.

Regulation is frequently used to change behaviour. Examples include enforcing speed limits and eliminating smoking from many public spaces. Regulation, however, has historically not been widely effective across all Australian jurisdictions to stop motorists entering floodwater, possibly due to enforcement resource limitations. Queensland Police have used the enforcement of driving laws during floods and drivers have been convicted of careless driving, resulting in fines, license disqualification, and custodial sentences. Motorists who remove temporary barriers to allow their vehicle to pass could also be prosecuted. In removing the barriers they ‘open’ the road to other vehicles and encourage risk-taking actions.

Source: floodwatersafety.initiatives.qld.gov.au

The Queensland Government’s ‘If it’s flooded, forget it’ campaign logo.

Road closure information could be streamed to vehicle-based GPS systems that may enhance driver awareness of local flood hazards and allow for alternate route planning to occur. Likewise, improved flash flood warning systems may allow for the closure of some roads before flooding occurs. Though enhancing safety this measure may, however, be criticised for causing unnecessary disruption if flooding does not eventuate.

A challenge for policy makers in developing a holistic approach is the lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of road closure interventions. Evaluation of existing activities is critical to assess the current influence on actual behaviour. Research is required to understand driver behaviour and to test and evaluate the effectiveness of new measures.

This study was limited to observing motorists decision-making in relation to relatively shallow and slow-moving floodwater. Further observational research would be beneficial to contribute to the findings of this paper and to inform the design of interventions, specifically to better understand demographics and the influence of vehicle passengers. To really understand the factors behind motorists’ decisions to enter floodwater it would be of benefit to interview motorists directly after they have driven through floodwater.

Motorists entering floodwater is a significant contributor to total deaths during a flood. The issue should not be regarded just as an emergency management problem but one also related to road safety and drowning prevention. Current measures being used have not proven successful in dissuading motorists from entering floodwater. Implementation of an holistic, national approach to reduce incidents of motorists entering floodwaters is needed.

PerilAUS is being updated with support from the Australian Bushfire & Natural Hazards CRC. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their time, expertise and useful suggestions in reviewing this paper.

See this video at www.youtube.com/watch?v=eI6mIlHKrVY.

Just 15cm of fast-moving water can knock over an adult and 30 cm of water can float a small car. Fast flowing water can carry vehicles away.

These are the messages illustrated in a simple recon-struction video by the U.S. National Weather Service.

Flooding is one of the leading causes of weather related fatalities and most deaths occur in motor vehicles when people attempt to drive through flooded roadways. This is because people underestimate the force and power of water, especially when it is moving.

It is difficult to tell the exact depth of water covering a roadway or the condition of the road below the water.

It is never safe to drive or walk through flood waters.

Ashley ST & Ashley WS 2008, Flood fatalities in the United States. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 47, pp. 805-818.

Becker J, McClure J & Davies B 2011, Never drive, ride or walk through floodwater: Pedestrian and motorist behaviour in and around floodwater. NSW Floodplain Management Conference. Tamworth.

Coates L 1999, Flood fatalities in Australia, 1788-1996. Australian Geographer, 30, pp. 391-408.

Coates L, Haynes K, Gissing A & Radford D 2014a, The Australian experience and the Queensland Floods of 2010–2011. Drowning. Springer.

Coates L, Haynes K, O’Brien J, McAneney J & de Oliveira FD 2014b, Exploring 167 years of vulnerability: an examination of extreme heat events in Australia 1844–2010. Environmental Science & Policy, 42, pp. 33-44.

Diakakis M & Deligiannakis G 2013, Vehicle-related flood fatalities in Greece. Environmental Hazards, 12, pp. 278-290.

Diakakis M & Deligiannakis G 2015, Flood fatalities in Greece: 1970–2010. Journal of Flood Risk Management.

Drobot SD, Benight C & Gruntfest E 2007, Risk factors for driving into flooded roads. Environmental Hazards, 7, pp. 227-234.

Fitzgerald G, Du W, Jamal A, Clark M & Houxy 2010, Flood fatalities in contemporary Australia (1997–2008). Emergency Medicine Australasia, 22, pp. 180-186.

Franklin RC, King JC, Aitken PJ & Leggat PA 2014, ‘Washed away’—assessing community perceptions of flooding and prevention strategies: a North Queensland example. Natural Hazards, 73, 1977-1998.

Gissing A 2015, Reducing deaths from driving into floodwaters. Crisis Response Journal, 11.

Gissing A, Haynes K, Coates L & Keys C 2015, How do we reduce vehicle related deaths: exploring Australian flood fatalities 1900-2015. Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC & AFAC Conference. Adelaide.

Haynes K, Coates L, Leigh R, Handmer J, Whittaker J, Gissing A, McAneney J & Opper S 2009, ‘Shelter-in-place’ vs. evacuation in flash floods. Environmental Hazards, 8, pp. 291-303.

Jonkman SN & Vrijling J 2008, Loss of life due to floods. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 1, pp. 43-56.

Jonkman SN & Kelman I 2005, An analysis of the causes and circumstances of flood disaster deaths. Disasters, 29, pp. 75-97.

Kellar D & Schmidlin T 2012, Vehicle-related flood deaths in the United States, 1995–2005. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 5, pp. 153-163.

Maples LZ & Tiefenbacher JP 2009, Landscape, development, technology and drivers: The geography of drownings associated with automobiles in Texas floods, 1950–2004. Applied Geography, 29, pp. 224-234.

Pearson M & Hamilton K 2014, Investigating driver willingness to drive through flooded waterways. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 72, pp. 382-390.

Ruin I, Gaillard JC & Lutoff C 2007, How to get there? Assessing motorists’ flash flood risk perception on daily itineraries. Environmental Hazards, 7, pp. 235-244.

Shand T, Cox R, Blacka M & Smith G 2011, Australian Rainfall and Runoff Project 10: Appropriate Safety Criteria for Vehicles.

Sharif H & Chaturvedi S 2015, Long-term trends in flood fatalities in the United States. EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, 17, p. 8113.

Sharif HO, Hossain MM, Jackson T & Bin-Shafique S 2012, Person-place-time analysis of vehicle fatalities caused by flash floods in Texas. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 3, pp. 311-323.

Špitalar M, Gourley JJ, Lutoff C, Kirstetter PE, Brilly M & Carr N 2014, Analysis of flash flood parameters and human impacts in the US from 2006 to 2012. Journal of Hydrology, 519, pp. 863-870.

Terti G, Ruin I, Anquetin S & Gourley JJ 2015, Dynamic vulnerability factors for impact-based flash flood prediction. Natural Hazards, 79, pp. 1481-1497.

Tey LS, Ferreira L & Wallace A 2011, Measuring driver responses at railway level crossings. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43, pp. 2134-2141.

Yale JD, Cole TB, Garrison HG, Runyan CW & Ruback JKR 2003, Motor Vehicle—Related Drowning Deaths Associated with Inland Flooding After Hurricane Floyd: A Field Investigation. Traffic injury prevention, 4, pp. 279-284.

Andrew Gissing is Director, Government Business and Enterprise Risk Management, Risk Frontiers at Macquarie University. He is a former Deputy Chief Officer of the Victoria State Emergency Service. His main areas of expertise are in disaster risk management, resilience and research.

Dr Katharine Haynes is a Senior Research Fellow, Risk Frontiers at Macquarie University. Areas of interest include the social dimensions of disasters.

Lucinda Coates is a Catastrophe Risk Scientist, Risk Frontiers at Macquarie University. Areas of interest include natural hazard damage and fatality analysis.

Dr Chas Keys is an Associate at Risk Frontiers. Chas is former Deputy Director General of the NSW State Emergency Service. His main areas of expertise are in flood emergency management and research.

1 SES FloodSafe. At www.floodsafe.com.au.

2 National Weather Service, ‘Turn around don’t drown’. At: www.nws.noaa.gov/os/water/tadd.