By journalist Rosemarie Lentini

Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Booth, Executive Director, Stephenson Disaster Management Institute, Louisiana State University.

We cannot plan for the future by looking at the past.

Climate change, ageing populations, terrorist threats and emerging technologies are contributing to a world of increased uncertainty. Only by scanning the horizon for long-term trends can emergency managers plan for a more resilient future. That is the advice of strategic foresight expert Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Booth, Executive Director of the Stephenson Disaster Management Institute at Louisiana State University in the United States.

Lieutenant Colonel Booth was Deputy Superintendent of Louisiana State Police when hurricanes Katrina and Rita hit America’s Gulf Coast in 2005. During the two storms, he was the Chief of Special Operations, overseeing special weapons and tactics (SWAT), hostage negotiation and crisis response operations. His role included commanding and coordinating the emergency response to Katrina and Rita.

‘We have been saying for decades, the world’s a smaller place. A few years ago, things that happened on the other side of the world may not have had any impact. Now they may,’ Lieutenant Colonel Booth said.

‘Strategic foresight is about looking at the trends—regionally, nationally, internationally—and how they affect even the most local emergency manager. Although they may not be within the ability of a local emergency manager to influence, they may cause disruptions in the local environment. Even the root cause of them is to be understood so you can anticipate possible consequences in your local authority.’

In July 2014, Lieutenant Colonel Booth addressed the Australian Emergency Management Institute Connections! conference in Mount Macedon, Victoria. In his presentation, he said that countries around the world continue to be caught off guard by major crises. From the devastating spread of Ebola in 2014 to the growing threat of terrorist network Islamic State, disasters often cross political and geographical borders. However, he said that governments can prepare for future risks by taking a ‘what if?’ approach to disaster planning.

‘Governments are increasingly at risk of cyber-attack as business-critical information is stored and processed online. Agencies should be asking: In the event of a security breach, do we have the tools to recognise, stop, and recover from the attack? Have we taken stock of our most critical assets and the impact on operations if they were stolen? How will we manage the risk?’ Lieutenant Colonel Booth said.

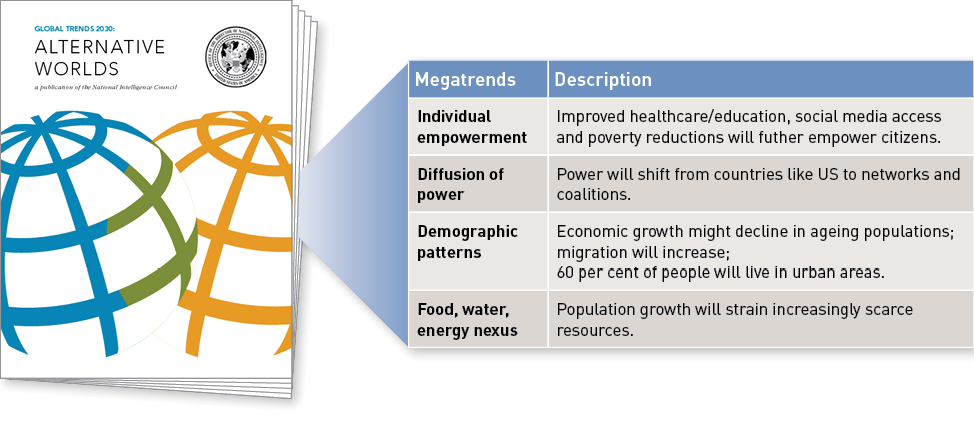

The experienced strategist said governments and emergency managers have access to a plethora of reports to help identify future global threats, including the influential Global Trends Report. Produced by the National Intelligence Council (NIC) within the United States government, the report aims to stimulate thinking about rapid and vast geopolitical changes.

According to the latest report, Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds1, the next 15 years will see the diffusion of power from hegemons to local networks, rapid population ageing, resource scarcity and the potential for more pandemics.

For Lieutenant Colonel Booth, Hurricane Katrina is a ‘good example’ of how the use of strategic foresight in disaster management ‘could mean the difference between a quick recovery and a protracted one’. Hurricane Katrina, one of America’s most catastrophic disasters, unleashed its fury on New Orleans in August 2005, killing 1 833 people. Levees failed, leaving 80 per cent of the city flooded and thousands stranded. Katrina destroyed hospitals, crippled emergency communication systems and destroyed local and state governments. A decade on, many individuals and businesses are still struggling.

‘One of the problems with Katrina was that we were preparing for the last event that we had rather than preparing for future consequences,’ Lieutenant Colonel Booth, who was right in the thick of it, said.

‘We knew what the weaknesses of the city were. We knew that the city was below sea level. We knew that it was prone to flooding. We didn’t know how vulnerable the levee was. We didn’t know that it was constructed in such a manner that it would eventually allow it to fail. So I guess foresight is not assuming your defences are as reliable as you want to assume they are.

‘We were planning by and large for the disaster to be inside of a scale in which we could respond. We were also assuming that the model of response would continue to apply. We’d never had an incident where it hadn’t, so we didn’t even think in that regard.

This bridge in Empire, Louisiana, was closed for almost 60 days after Hurricane Katrina went through the area in 2005.

‘Hurricane Katrina did away with local authority. It destroyed the local capability and the whole model of response. We had to reinvent how to respond on the run while we were coping with the disaster.

‘Looking back now, I can say I wish we would have planned for a bigger disaster of greater magnitude. But I think we have a tendency to prepare to the limit of our resources. Katrina is proof that you also have to prepare for events far beyond the management ability of local resources,’ Lieutenant Colonel Booth said.

Lieutenant Colonel Booth also said one of the lessons of Katrina was the need for individuals to prepare themselves for disaster. This will be even more important in the future as economic constraints force governments to slash budgets.

‘I think one of the main effects of Katrina is that it has reinforced the ethic that people have to be more prepared to be on their own and not assume the government is going to be there to take care of their emergency needs, especially in the first 72 hours.

‘Because when you look at government resources, and here is a little strategic foresight, you see government cutting back, able to provide less services and at the same time demand for services may be going up because the magnitude of disasters is increasing. So what has to happen is that people have to be more reliant on themselves, their neighbours and not on government infrastructure,‘ Lieutenant Colonel Booth said.

The experienced emergency commander now heads a United States institute which works to improve disaster response management through research and education. With the world’s best intelligence at his fingertips, Lieutenant Colonel Booth’s advice for emergency managers is to fight the tendency to plan only for expected risks.

Lieutenant Colonel Booth said, ‘We have a tendency—and it’s a natural tendency—to look at the future in terms of what’s happening now. We have to look at the future in terms of the future. How are we going to operate in new and changing environments and how do we apply those tools?’

1 View the United States National Intelligence Council - Global Trends Report at: www.dni.gov/index.php/about/organization/national-intelligence-council-global-trends