This paper describes the influence animals can have on human behaviour in emergencies. Emergency services organisations use a mandated and consistent hierarchy on which to prioritise and focus their core business – people, property, and the environment. Yet, in each of these categories, animals can be found.

People: The assistance an animal accompanying an evacuee (without which the evacuee may be unable to function in the community) needs to be considered as an inseparable extension of the hazard-impacted person requiring rescue. This category calls for extra consideration by rescuers and at an evacuation centre for provisions beyond the norm.

Property: Livestock are owned by primary producers, companion animals are owned by families and individuals. Horses and racing greyhounds might be variously considered as stock, as an economic unit, or as family pets. All these bring physical and emotional parameters to ownership. The welfare of these animals is the responsibility of the owner, best dealt with by inclusion in the family or property survival plan before an event. However, emergency response invariably includes rescue, either aligned with the welfare of families or for managing the hazards of animals wandering at large.

Environment: These may be animals such as wildlife, or animals wandering-at-large that have been separated from their owners. They may become a collision hazard for emergency services vehicles. Where iconic local species are held in protective high regard by a community, carefully nurtured community resilience can be severely diminished if such animals are adversely affected by the event. Then there are those family animals that may be left behind, as last-minute human evacuees flee for their lives: the guinea pig, the dog or the pony left to suffer their own fates.

Information for this paper exploring how people relate to animals in emergencies is drawn from a wide variety of naturally-occurring data. Historical accounts, reports from contemporary events, and, in particular, the photographic records detailing real-time emergencies represent a mix of literature and anecdotal sources that form a cohesive narrative.

The events chosen are sequentially arranged as:

These have been selected as providing a diverse baseline over an extended period of time and include the following recurring themes.

In emergencies, people may act, as they see it, in the best interest of an animal. Consequently, decisions may be taken that are adverse to their own personal safety and survival. The public record uses images and references to specific animals as a method to engage society on the effects of emergencies on communities.

Most people dislike the thought of an animal dying a frightening, painful and possibly prolonged death, but an animal image may be less confronting and more broadly acceptable to society, instead of images of devastation and human tragedy. While images of people caught up in the worst effects of an emergency event are broadcast on the nightly news, these are rarely repeated with the frequency of those of the animal ‘mascot’. The sub-text is the idea suggested by the extrapolation from animal to human victim. What happens to the animal could happen to the human. Thus, such images have been used in the hope that people will be motivated to engage in good preparedness measures for their own household, whether they own animals or not.

Just over a century ago, the transatlantic liner, RMS Titanic, sank on her maiden voyage after colliding with an iceberg. The records of rescue vessels detailed the observations in the aftermath. Beyond the expected rats and mice, the ship also carried animals as cargo (e.g. breeding dogs and poultry on export to the United States), as deliberate additions to the crew (the galley’s cat and her kittens) or as a complement of companion animals belonging to some of the guests on board - principally cats and dogs - some being housed in the first-class cabins.

Some of the evacuees decided to either smuggle their pet onto a life boat hidden in clothing or to refuse to board a lifeboat unless the dog came too. In one case, where the dog was refused lifeboat passage, rescue crews several days later found the bodies of owner and dog still clinging to one another (Eaton 1999, Geogiou 2000).

In 2005 Hurricane Katrina breached the levees surrounding the low-lying portion of urban New Orleans. Enormous numbers of evacuees (both human and animal) needed rescue, relocation and support. Conservative estimates of animal deaths due to Hurricane Katrina are in the thousands (Rizzuto & Maloney 2008, Irvine 2007). The Humane Society of the United States and the Louisiana Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals estimate 727 500 animals were affected by Katrina (Irvine 2007).

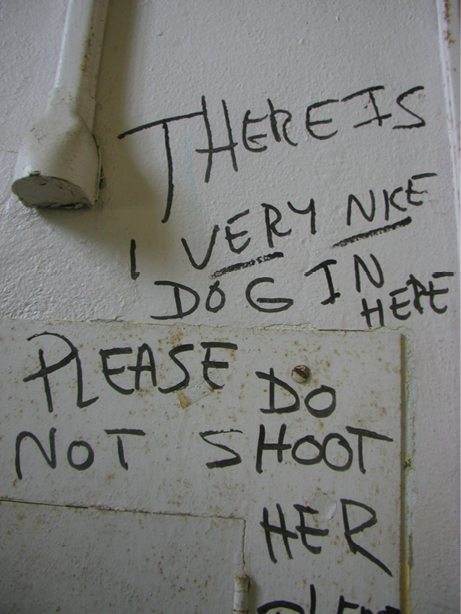

Stranded or abandoned animals in the emergency affected area were shot by armed responders, the official decreed policy at the time. Animal owners with no choice but to leave their beloved pets painted notices on their homes about the animals within, pleading for them to be left alive. Over 15 000 animals, including livestock and horses were rescued, although only about 2 300 were reunited with owners (Bryant 2006, Scott 2006).

Animal owners painted notices on their homes about the animals within, pleading for them to be left alive.

A number of barriers to evacuation were experienced, including the exclusion of companion animals from evacuation centres (Irvine 2007, Rizzuto & Maloney 2008). This had effects beyond the displacement of evacuees from their own animals: therapy animals normally used in social programs at evacuation centres as part of outreach to evacuees could initially not enter. When arrangements were later made for that access, entry was slow because officials themselves wanted to stop and pat the animals as a means of personal emotional relief (Chandler 2012). Laughing groups of children followed the animals and the atmosphere changed from dour and unresponsive evacuees to one of noticeably positive engagement, triggered by the presence of the animals (Chandler 2012).

The powerful story of ‘Katrina’ the beagle describes the 13-hour rescue mission of an American air force helicopter crew deployed to New Orleans during the infamous storm. In that 13 hours, 184 people, six dogs and two cats were winched to safety, including, at the very end, a beagle who had been present for the whole day. The small dog appeared to herd people towards the helicopter and the crew enjoyed seeing her intrepid behaviour beneath the rotor wash. ‘Katrina’ became the mascot of the 920th Rescue Wing at Patrick Air Force base in Florida and is the star attraction at fundraising events for local animal shelters. She has buoyed the spirits of many military personnel at the Patrick base, including those returning from traumatic service in Afghanistan (Kime 2013).

An American air force helicopter crew rescues 184 people, six dogs and two cats, including ‘Katrina’ the beagle.

An Australian parallel to the New Orleans experience occurred in the Queensland floods of January 2011, including the efforts of Emergency Management Queensland’s Rescue 500 helicopter. They record one pet, a kitten, jumping and clinging onto the person being winched into the helicopter from the flood-bound rooftop below. With a ‘no pets’ rule, the crew only discovered the stowaway when back on solid ground (Coulthard 2011, Woodward 2011).

Other images from these floods include horses attempting to clamber onto roofs, and the injuries they received from sharp roofing iron and guttering. The photographs also show the efforts by people to rescue these animals.

The 2009 bushfires in Victoria left devastation in terms of whole communities, families, properties and the environment. All species of animals were inevitably affected. The resonating visual image from this event was ‘Sam the Koala’, photographed with a Country Fire Authority volunteer. This is the genesis of an animal image coming to represent an individual emergency event.

This 2014 bushfire impacted on the local population of iconic white kangaroos. The local community values this mob as an identifier of the area. Efforts by locals working in collaboration with Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources officers and with external support acted to ensure survival of the white kangaroos in the recovery phase after the fire (Vigar 2014).

White kangaroos are iconic for the Billiatt Conservation Park, South Australia.

The final theme is that of the iconic animal representing an individual emergency event, sometimes with a human attached, sometimes not. Hurricane Katrina included the tale of ‘Snowball’, a fluffy white dog confiscated from the arms of a screaming child by a police officer as the child boarded an evacuation bus. The child screamed until he vomited, and Snowball was never seen again (Irvine 2007).

‘Sam the Koala’ was the image of the Victorian 2009 bushfires that captivated the world, and helped raise donations for the Country Fire Authority. In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico became identified by the oiled Pelican.

The image of an animal ‘mascot’ representing individual emergencies has been seen elsewhere, such as ‘Cinder the bear’ in the 2014 Carlton Complex Fire in Washington State. These images convey a sense of compassionate response by all affected. Sometimes the reality is that these iconic animals are not long-term survivors due to pre-existing medical conditions, which may be exacerbated by superimposed physiological stress.

Images of overwhelming human tragedy in emergencies are considered inappropriate and inhumane, and are not acceptable to be displayed regularly in the mass media. Animals in this context represent a ‘buffer’ - the image of the animal is less traumatic, possibly even conveying a message of hope.

This paper examines decisions by people in emergencies with respect to the welfare of animals. Written and photographic evidence in this historical review illustrates the propositions in this paper.

There are a number of consistent reminders that:

Bryant S 2006, No way would we put them down: Animals still homeless after Katrina. Houston Chronicle, April 22.

Chandler CK 2012, Animal assisted therapy in counselling, New York, New York: Routledge.

Coulthard R 2011, Rescue 500. Sunday Night. Channel 7.

Eaton JP & Haas CA 1999, Titanic: A Journey Through Time, Sparkford, Somerset, Patrick Stephens.

Geogiou I 2000, The Animals on board the Titanic. Atlantic Daily Bulletin. Southhampton: British Titanic Society.

Irvine L 2007, Ready or Not: Evacuating an Animal Shelter During a Mock Emergency. Anthrozoos, 20, pp. 355-364.

Kime P 2013, Saved from Katrina, beagle retires to Florida as rescue wing mascot. Military Times. Springfield: Gannett.

Rizzuto TE & Maloney LK 2008, Organizing chaos: Crisis management in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, pp. 77-85.

Scott RT 2006, Get animals out of town, too, bill suggests: Legislation would provide a place for pets during an evacuation. Times-Picayune, April 18. Tedeshi RG & Calhoun LG 2004, Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundation and Empirical Evidence., Philadelphia, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Vigar S 1 February 2014, RE: The Billiat White Kangaroos. Personal communication.

Woodward J 2011, Mark Kempton, Senior helicopter pilot. In: State Library of Queensland (ed.).

Dr Rachel Westcott is Director and Principal Veterinarian, HomeCare Vet to Pet Mobile Veterinary Services in Adelaide, South Australia, and Coordinator of South Australian Veterinary Emergency Management (SAVEM Inc.). She is concurrently a PhD candidate on the University of Western Sydney and Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC project, ‘Managing Animals in Disasters: improving preparedness, response, and resilience through individual and organisational collaboration’.