| Wildfires are becoming a greater concern in many areas of the world. In this article, focus is on wildfires in two rural communities in Canada with emphasis on the aftermath at both the individual and community levels. Through open-ended interviews, information was generated about individual experiences with recovery and the creation of groups in the communities post-wildfire. The findings reveal that despite the differences in the severity of the fires, residents at both sites experienced impacts after the event. Disaster management implications include the need to focus on all community residents, not just those who experienced losses, while investing in the social rebuilding of communities. |

Wildfires are becoming a greater concern for a variety of reasons including climate change and increasing residential densities in wildland-urban interface areas (Brown, Hall & Westerling 2004, Ostry et al. 2008). Analysing past wildfire events offers the opportunity to document and understand evacuation and recovery experiences of individuals.

Research literature about the human and social impacts of such events on individuals and communities is limited, inconclusive, and equivocal. Some literature exists about mental health effects (Usher-Pines 2009) including research demonstrating an elevated risk for psychopathology among evacuated residents who sought emergency relief services (Marshall et al. 2007). Jones et al. (2002) examined the psychological impacts of fires on children and their parents and concluded that those with high losses had higher levels of post-traumatic stress disorder. However, the literature is contradictory and inconclusive about the temporal effects and duration of such responses for those who experience wildfires (Jones et al. 2002, McFarlane, Clayer & Bookless 1997).

Studies conducted in several American states confirm that in communities which have experienced wildfires, cohesion and conflict frequently occur among individual community members (Blatner et al. 2003; Carroll et al. 2005; Carroll et al. 2006). Carroll et al. (2005) found there were tensions between and within such communities attributed to variations in fire-related experiences. Tensions were experienced due to evacuation experiences (Cohn, Carroll & Kumagi 2006), fire attack processes (Carroll et al. 2005, Whittaker & Mercer 2004), or recovery experiences (Carroll et al. 2005). Findings from the Lost Creek Fire experience revealed that community cohesion and functioning were positively affected post-wildfire (Reimer et al. 2013). This growing body of literature provides an enhanced understanding of the wildfire experience but there is no concluding evidence about the connection, if any, between personal property losses and the impact of the event. This article reports on the aftermath from wildfires as experienced by the two rural communities in western Canada to answer the following question: ‘Does the severity level of wildfires based on loss make a difference to the experience of individual and community impacts?’

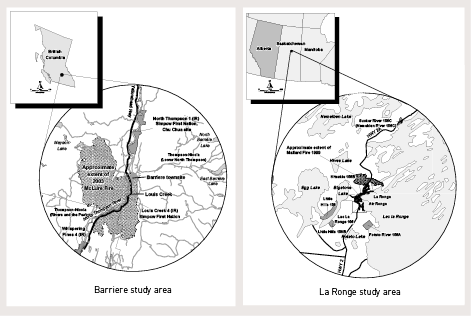

Assessment of the Canadian National Disaster database (2012) generated a list of communities that had experienced wildfires with significant property damage and evacuation. From this list two communities in rural areas were chosen for further examination1. The first, in the Barriere area of central British Columbia, was the location of the 2003 McLure Fire caused by human error (the discarding of a lit cigarette as reported in Filmon 2004). It resulted in the evacuation of over 3 000 residents from several communities, the loss of 90 structures (homes, barns and other outdoor buildings), and burned 26 420 hectares of forested land.

Importantly, the community’s major source of employment—a sawmill—burned down in the fire and was never rebuilt, adding to the losses experienced by the community. The second site, LaRonge, in northern Saskatchewan is comprised of three adjoining communities (the town of LaRonge, the village of Air Ronge, and the Lac La Ronge Indian Band2). It was the site of the 1999 Mallard Fire that was ignited by a lightning strike. Several hundred people were evacuated while the fire moved rapidly over an eight kilometre front, destroying 13 homes, ten of which were in an exclusive lakeside area.

The larger multi-methods study examined the links between wildfire experiences and community resilience (Kulig et al. 2011, Kulig et al. in press). It was conducted in collaboration with the participating communities using local advisory committees, local research assistants, and visits to the sites to conduct field work and discuss the findings. This article details the qualitative interviews conducted at both sites.

The research assistants were trained before conducting the 57 interviews in 2008 with residents from the two participating communities. Purposeful sampling was used to ensure that key organisations, policy-makers, and citizens affected by the fire recovery efforts were included in the sample. Subsequent to providing informed consent and completion of a demographic form, the research assistants used a series of open-ended questions to determine participant assessment of the community and fire experience. Examples of these questions include: ‘How do you define a community?’, ‘What was your role in the community during and after the fire?’, and ‘What is the community like since the fire?’ All of the interviews were recorded and confidentially transcribed. There were no refusals and data saturation was reached after 30 interviews at the McLure site and after 27 interviews at the La Ronge site.

Transcripts were analysed while the interviews were being conducted. This involved recording notes and re-reading the documents and reflecting on their meaning (Liamputtong 2013). In thematic analysis, frequent comparisons between and within the interviews occurs in order to identify common categories that describes the participants’ perspectives (Schatzman & Strauss 1973). The categories led to the development of themes that were discussed with the advisory members to ensure the data were analysed appropriately for each local context. During this process, teleconference meetings were held with the research assistants to discuss the preliminary findings and ensure that clarification of emerging issues was achieved.

The adult participants included both genders and represented a range of professions. Participants experienced evacuation, helped fight the fires (as professionals and as individuals trying to save their home), and assisted with the recovery efforts of their communities or neighborhoods. While some participants had left the La Ronge area, the majority remained in the community after the fire, so the interview responses represented a local perspective of the events and their aftermath.

All participants were asked to discuss being a member of their community and their perceptions of the community’s cohesion and resilience. Both the communities were described as friendly, welcoming, and caring with a strong sense of identity. In addition, both were described as having resilient characteristics, including cohesiveness, a willingness to help one another, a sense of community pride, and leadership that was proactive in addressing concerns.

‘Feeling Closer’—‘Lingering Effects’

The findings revealed a range of emotional effects from the fires. ‘Feeling closer’ was a common expression used by people in both communities. One woman from Barriere summarised a common sentiment among the participants as:

‘I was really amazed how we were so taken care of and how everyone pulled in together. I really think that the fire really brought this community together.’

According to some, a greater sense of community cohesiveness had occurred since the disaster with an overall decrease in negativity. One female participant from La Ronge talked about how the experience of the disaster created a different kind of mentality among community members:

‘You’re part of my group now, because that happened to me, so maybe that brings us closer together or suddenly where we had no other reason to be friends or anything, we become friends. And probably disasters bring people closer together faster.’

After the fire, groups such as the local Search and Rescue and the Emergency Social Services experienced an increase in volunteerism that was attributed to the sense of caring for one another.

Even though positive outcomes from the fires occurred, there were individuals who spoke about the personal negative impacts of the event. Lingering effects from the fires, including physical and mental health symptoms, were experienced. These individuals found it difficult to cope with their losses. Other participants said they continued to fear that a fire would happen again: a fear that could simply be triggered by the smell of smoke. One woman from Barriere described it in this way:

‘They just can’t let go of fear. We never thought it would happen and now we know it can happen, so we think it’s going to happen again.’

Feeling fragile in the wake of the fire was a common experience for individuals from both communities. One of the male participants from Barriere said,

‘Before the fire I was fearless and capable of taking on the world’, while another man from the same community said, ‘I didn’t feel I was alive until a year after the fire’.

The participants noted that the families who had lost homes in Barriere were under stress immediately after the fire. These families had to make decisions about rebuilding and how to manage financially, particularly because a number of them had no property insurance. For some of these families, the decision to curtail having property insurance, due to its high cost, led to guilt, regret, or frustration after they lost their home.

Image: Dr Ivan Townshend

Landscape around Barriere from the wildfire impact.

There were individuals in both communities who had ongoing difficulties with the fires, even though they may not have experienced being evacuated, or may not have lost their home or possessions.

One woman from La Ronge said:

‘I didn’t personally lose a home, but I couldn’t face it. I couldn’t look at it because I knew there was so much pain and so much loss and people had lost irreplaceable items. It was very, very difficult because those extreme emotions lasted all through the summer.’

In contrast, another female participant from the same community talked about the long-term emotional impact from the fire experience:

‘I know that for a year I was pretty screwed up. I got some therapy, I got some help. I left my job for two or three years, took a leave because I felt I wasn’t in any shape to be able to be supervising people or making decisions about people’s lives… And then the things that have happened to me since that fire – because that was a lot of loss, a lot of grief, and it wasn’t – it’s not your belongings, it’s never your belongings. And I mean, I loved my house and I loved where I lived, but it’s your animals and – I’ve always kept journals so I had journals since I was five years old, and I had pictures. So it’s your history, you know, that got wiped out.’

Interviews also revealed that other community members were also struggling after the fires. Fatal heart attacks were perceived to be on the increase in the months following the fire in Barriere and concerns about a cancer increase linked to the use of fire retardants were mentioned. One female participant from Barriere said:

‘You look at people that have health problems, and they were holding their own for a while and then they went downhill. We lost quite a few after the fire. Since that time there have been major health issues in the community and the rates of cancer have been high. I’m not sure if our community has blown up because of the fire or what, but it is horrendous the amount of people who are getting cancer.’

Image: Brent Kravetski

The Mallard Fire threatened the lakeside resort.

These beliefs were held by participants in both communities and therefore appear unrelated to the severity of the event. A male participant from

La Ronge said:

‘If you ask my father today he believes the fire is what killed my mother. That she ended up in such an emotional state around that time that her cancer came out. I mean, that’s his belief. I don’t know if I believe that. I mean, I believe that yeah, cancer lives in us all and yes, it is a big event sometimes or your body gets run down or something and suddenly that cancer becomes stronger than your good stuff. Was it the fire?’

Despite comments that people felt closer after the fires, there was evidence that several contrasting perspectives and experiences became important within the communities. After the McLure Fire these were:

There was no evidence of outright conflict within the community related to these differences but they have the potential to serve as bases for social tensions.

One woman from Barriere referred to the first contrast as:

‘I think in some instances they [impacts of the fire] are still ongoing. A lot of people have forgot and are willing to go on. But there is always that small element that seems to resist change. I think that some people have been changed for the rest of their lives from the fire.’

Another male participant from Barriere described the third contrast as:

‘There are some who just can’t let it go. I heard that people who go through great tragedies in their lives like to talk about it a lot, and part of that is trying to make sense of it. I think that is okay if you’re a positive person. I think that there’s a number of people who just can’t seem to get past the fact that we had this tragedy and we lost members of our community who had to move away and took their young families with them. It hugely impacted us and it was a tragedy, but we have to move on and fight back.’

One issue that contributed to these different responses in the McLure Fire was the reaction by some participants about the assistance provided to those whose property was not insured. More specifically, a non-profit organisation built homes for individuals with no house insurance. Comments were made that these individuals were now living in homes that looked considerably better than their original mobile homes. In addition, some individuals who had their homes replaced through their insurance company chose to leave the community to secure employment elsewhere after they learned that their workplace (i.e. the Tolko mill) was not going to be rebuilt. When they sold their newly-built homes, rumours circulated that these individuals did not abide by proper insurance company regulations that you had to own and live in the home for a year before you could sell it. Checks with the insurance regulatory board confirmed that no such regulation existed.

In the Mallard Fire situation, two different sets of viewpoints emerged. One perspective was that those who lost their homes did not need assistance, while the other was that those who lost their homes did not receive the assistance they needed. Some of the participants assumed that those who lost their homes at the lakeside resort area were generally more affluent, had the resources to rebuild, and thus, did not need any type of assistance.

The participants from the lakeside resort area who had experienced the most losses indicated they would have appreciated assistance from the wider community. They talked about how their loss was accentuated by living in a community environment that did not acknowledge their significance. Other viewpoints also emerged in the interviews. Some of the individuals who had lost their homes simply wanted time to reflect and deal with their loss, which may have been interpreted by the community residents as rejection. In Barriere there was a perception that separating those who experienced significant physical losses from those who had not was an inappropriate way to proceed. One participant described it as the development of an ‘exclusive club’ for which community help was not welcome.

Image: Dr Judith Kulig

The Barriere monument for the fire is a ‘fire dragon’, carved out of an old-growth cedar tree for the anniversary event in 2008, five years after the fire.

In spite of the suggestions that reactions to wildfires may be affected by the size of the wildfire, its intensity, and duration (Kumagai et al. 2004), research found that individual responses to wildfires were not always related to property losses or with being evacuated. Individuals who were not evacuated and experienced no losses, still reported emotional impacts—in some cases, they also experienced physical or perceived physical effects. More information about these variations of responses by community residents who experience various types of wildfires is needed to understand the impact (Marshall et al. 2007) and the duration of the effects, and to determine appropriate disaster recovery efforts. The findings suggest recovery efforts should not focus solely on those who experienced losses.

The fires also provided the opportunity for the communities to become more cohesive and supportive of one another. However, this was not always put into practice. Unlike other investigations (Carroll et al. 2005) there was little conflict noted in the communities studied.

A closer examination of this phenomenon in other wildfire communities in different social and economic contexts (e.g., publically- and privately-funded health care) would be worthwhile to determine the conditions under which social conflict results after wildfires. Furthermore, identifying the most likely social attributions and related interaction changes that occur post-wildfire will enhance the understanding of social conflict (Tajfel & Turner 1986).

The findings suggest that post-wildfire investment in social rebuilding and community resources would help mitigate negative effects. National policies to ensure disaster resilience also highlight the importance of a shared responsibility between government and community members to prepare for and address disasters (Commonwealth of Australia 2011). From the findings, it is suggested that this shared responsibility includes ensuring all members of communities receive timely access to services, whether or not they experienced loss.

Additional studies about the impacts of wildfires on individuals and communities are needed. Most importantly, we require clarification of long-term health, social, and financial problems that may result due to wildfires, regardless of evacuation experiences or losses. Research findings from such investigations have the potential to heighten awareness, understanding and attention to the short and long-term human and social effects of wildfires among relevant emergency and disaster agencies.

Blatner, K, Mendez, S, Carroll, MS, Findley, A, Walker, G, & Daniels, S 2003, Smoke on the Hill: A Comparative Study of Wildfire and Two Communities. Western Journal of Applied Forestry, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 60-70.

Brown, T, Hall, B & Westerling, A 2004, The impact of twenty-first century climate change on wildland fire danger in the western United States: An applications perspective. Climate Change, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 365-388.

Bryant, RA & Harvey, AG 1996, Posttraumatic stress reactions in volunteer firefighters. Journal of Traumatic Stress Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 51-62.

Canadian Disaster Database 2012. [1 January 2005].

Carroll, MS, Cohn, PJ, Seesholtz, DN, & Higgins, LL 2005, Fire as a Galvanizing and Fragmenting Influence on Communities: The Case of the Rodeo-Chediski Fire. Society & Natural Resources vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 301-320.

Carroll, MS, Higgins, L, Cohn, P & Burchfield, J 2006, Community wildfire events as a source of social conflict. Rural Sociology, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 261-280.

Cohn, PJ, Carroll, MS & Kumagai, Y 2006, Evacuation behavior during wildfires: Results of three case studies. Western Journal of Applied Forestry, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 39-48.

Commonwealth of Australia 2011. National Strategy for Disaster Resilience. Australia: Council of Australian Governments.

du Plessis, V, Beshiri, R, & Bollman, R November 2001, “Definitions of Rural” Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin, vol 3, no 3 Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE.

Filmon, G 2003, Firestorm 2003: Provincial review. British Columbia, Canada: Provincial Government of British Columbia.

Jones, RT, Ribbe, DP, Cunningham, PB, Weddle, JD & Langley, AK 2002, Psychological impact of fire disaster on children and their parents. Behavior Modification, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 163-186.

Kulig, J, Reimer, W, Townshend, I, Edge, D, & Lightfoot, N 2011, Understanding Links between Wildfires and Community Resiliency: Lessons Learned for Disaster Preparation and Mitigation. Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge.

Kulig, J, Townshend, I, Lightfoot, N, & Reimer, W 2013, Community Resiliency: Emerging Theoretical Insights. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(6), pp 758–775.

Kumagai, Y, Carroll, M, & Cohn, P 2004, Coping with Interface Wildfire as a Human Event: Lessons from the Disaster/Hazards Literature. Journal of Forestry vol. 102 no. 6, pp. 28-32.

Liamputtong P 2013, Qualitative research methods 3rd ed. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Marshall, GN, Schell, TL, Elliott, MN, Rayburn, NR & Jaycox, LH 2007, Psychiatric disorders among adults seeking emergency disaster assistance after a wildland-urban interface fire. Psychological Services, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 509–514.

McFarlane, A, Clayer, J & Bookless, C 1997, Psychiatric morbidity following a natural disaster: An Australian bushfire. Social Psychology and Psychological Epidemiology, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 261-68.

Ostry, A, Ogborn, M, Takaro, T, Bassil, K & Allan, D 2008, Climate change and health in British Columbia. University of Victoria: Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions.

Rehnsfeldt, A & Arman, M 2012, Significance of close relationships after the tsunami disaster in connection with existential health—a qualitative interpretive study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 537-544.

Reimer, W, Kulig, J, Edge, D, Lightfoot, N, & Townshend, I 2013, The Lost Creek Fire: An Example of Community Governance under Disaster Conditions. Disasters, 37(1).

Schatzman, L & Strauss. A 1973, Field research: Strategies for a natural sociology. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Tajfel, H & Turner, JC 1986, The social identity theory of inter-group behavior. In S. Worchel & L.W. Austin (Eds.). Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Usher-Pines, L 2009, Health effects of relocation following disaster: A systematic review of the literature. Disasters vol. 33, no. 1 pp. 1-22.

Whittaker, J & Mercer, D 2004, The Victorian Bushfires of 2002-03 and the Politics of Blame: a Discourse Analysis. Australian Geographer vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 259-287.

The Rural Wildfire Study Group is a multi-disciplinary research group which includes investigators, research advisory members and local community members. It focuses on the social impacts of wildfires in its ongoing research program.

1 Rural communities are defined as those with less than 10 000 residents outside the commuting zone of urban areas (du Plessis et al. 2001).

2 The Lac La Ronge Indian Band is the largest First Nation in Saskatchewan.