| Local government is an under-researched field in itself and its role in emergency management even more so. However, working with specialised responders, local government employees often play key roles during emergencies. Emergency management studies frequently pay little if any attention to these roles, subsuming them into consideration of the parts played by dedicated agencies and state and federal authorities. The neglect extends to consideration of the role of local governments in emergency communication. A survey targeting communication staff in Victoria's 79 local government councils set out to provide an initial study of this topic. The survey respondents provided some valuable material, especially expressions of interest in emergency communication training. This paper suggests that the pattern of survey responses may indicate that emergency communication roles need to be clarified at a local government level. It also outlines an agenda for future research. |

Local governments play a significant role in managing emergencies in Australia, even though the emergency management task falls mainly to state and federal governments (Australian Local Government Association [ALGA], n.d., para.3). There is a move to spread the burden of emergency management and the development of disaster resilience beyond authorities alone through a concept of ‘shared responsibility’. This means that ‘communities, individuals and households need to take greater responsibility for their own safety and act on information, advice and other cues provided before, during and after a disaster’ (ALGA n.d., para. 8). However, this focus expands rather than excludes local government involvement. Therefore, when it comes to emergencies, ‘the essential remedy to an emergency situation is almost invariably applied at the local level’ (Drabek & Hoefner 1991, cited in Alexander 2005, p. 161). As Alexander notes, ‘even the largest catastrophes have to be managed by marshalling resources in local units’ (2005, p. 161). This is consistent with Wilson’s advice (1989, in Kapucu 2011, p. 212) that authority in public services should be placed ‘at the lowest level at which essential information for sound decisions is available’. It is logical that local government should fulfil a frontline role in emergencies along with other specialised responders.

The importance of this role is recognised in a 2006 ALGA survey where more than 50 per cent of respondents regarded emergency management as a very important function of local government. Similarly, other countries value local government involvement. For example, in Canada, municipalities handle 95 per cent of all emergencies and are responsible for public security and emergency management (Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 2008, in Killingsworth, 2009, p. 61). Yet academic researchers seem to pay little if any attention to the local government/emergency nexus. Research is being produced on subjects such as local government engagement with communities (for example, Morris 2012) or how local authorities are using social media to engage with citizens (Howard 2011). Yet online Google search engine inquiries using phrases such as ‘local government communication’; ‘local government emergency communication’ and ‘local government public relations’, all with an Australian focus, reveal no on-topic responses at all. In part, this may result from a lack of perceived differentiation between the communication requirements of the public and private sectors. Communication management literature tends to treat the two domains as effectively identical despite an extensive survey identifying ‘far more differences than similarities in how the two sectors shape communication practices’ (Liu & Levenshus 2010).

Canadian researcher Colleen Killingsworth observed: ‘Despite extensive literature on the nature of organizational communication, and government communication at the federal, state and provincial level, there is little research exploring government communication at the local or municipal level’ (2009, p. 62). In Australia, an article on ‘The neglect of public relations in Australian public administration’ in The Australian Journal of Public Administration (Caiden 1961) does not appear to have prompted subsequent research since its publication more than 50 years ago. Killingsworth’s view is endorsed by Australian scholars, Simmons & Small (2012, p. 2), who note: ‘To date there has been little study or theorisation of the practice of local government public relations and communication in Australia, or elsewhere’ (Horsley, Liu & Levenshus 2010). This neglect carries over into the field of emergency communication and the role of local government communicators.

While the importance of effective communication in disasters or major incidents ‘cannot be overstated’ (Leadbeater 2010), The Australian Journal of Public Administration’s most recent coverage of emergency management (Boin & t’Hart 2010) offers broad advice on communication rather than the specifically local focus of this article. The authors draw on Hilliard (2000) to assert that forging effective communication and collaboration among pre-existing and ad hoc networks of public, private and sometimes international actors are one of nine different recurrent challenges of crisis response facing political office-holders, agency leaders and other senior public executives at a strategic level. They also note that at the tactical and operational level, incident commanders and operations managers need to inform and empower communities by transmitting accurate, timely and actionable information upward, outward and downward within the crisis response structure, as well as to relevant citizens and communities, designed to enable these actors to make informed crisis-response decisions within their respective domains of involvement (Boin & t’Hart 2010, p. 360).

Crisis management, say Boin and t’Hart, ‘critically depends on smooth communication flows within and between organisations’ (2010, p. 362). It is these communication flows for which professional communicators in local government bear some responsibility on a day-to-day basis; experience which becomes vital in the case of an emergency.

The survey was intended to capture information about local government communicators within the wider emergency planning, response and recovery context. The methodology was a purposive sample of these communicators in the state of Victoria conducted via an online survey using the survey creation tool SurveyCreator. While a wider survey would have been instructive, limiting inquiry to Victoria was sufficiently indicative as an initial exploratory study. The survey was constructed with assistance from the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV), which promoted the survey via its newsletter to Victorian local government councils. The sample was therefore derived from council staff members responding to the MAV promotion. Respondents accessed the survey website, completed the survey and submitted it electronically. Submissions were returned to the MAV and passed to the researcher as de-identified responses.

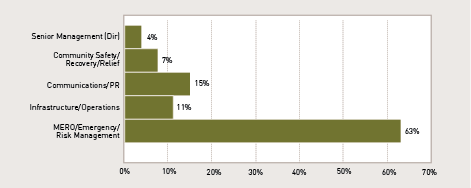

Figure 1 shows the mix of position titles that survey respondents nominated. Of those responding, 23 had the title of Municipal Emergency Response Officer (MERO) and did not have the term ‘communication’ in their job title. Only 15 per cent (n=4) had a title that clearly reflected a communication or public relations function. This was not expected and the responses did not indicate why a number of MEROs rather than colleagues with direct communication responsibilities replied. Nevertheless all respondents were able to provide informed opinions about emergency communication. As illustration, MEROs are response co-ordinators who call in specialist communication support as needed (P Fitz, personal communication, 18 October 2012).

Figure 1. Details of survey respondents’ position titles.

Most responses came from council staff who for day-to-day operations report to a manager or team leader position. This was especially marked in rural local government councils, where the majority reported to a manager. A significant number of rural respondents (n=8) were responsible to a general manager, director, or chief executive. In total, a third of the senior positions identified were responsible for overall management of a council. Some, such as Director, Environment and Infrastructure, were responsible for a specific unit or department. In many cases these reporting responsibilities were maintained in the case of an emergency, with a combined total of 33 per cent (n=9) accountable to senior management. A minority (11 per cent, n=3) were under the guidance of an external agency such as the police or the State Emergency Service.

Respondents’ relationships with both local government council and external emergency management response personnel appear to be robust. Referring to council emergency staff, a combined (metropolitan/rural) total of 20 respondents (72 per cent) indicated they had an ‘excellent’, ‘close’, ‘strong’ or ‘good’ relationship with these colleagues. The view of relationships with external personnel was even better—a combined total of 75 per cent (n=20) indicated ‘excellent/brilliant’ or ‘strong/good/supportive’ to characterise these connections. Inside local government councils, only one respondent described the relationship as ‘frustrating’ while three indicated that relationships were merely operational or functional. Externally, two responses described the relationship with external emergency response staff as ‘distant/non-existent’.

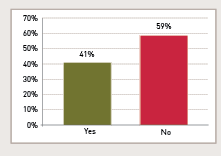

All respondents reported being trained in emergency management but not all thought this training was necessary. Two, from rural councils, thought it was not. Most respondents reported carrying responsibilities for emergency planning and training (63 per cent, n=17), although for 26 per cent (n=7) the focus was on anticipating communication and media demands. In an emergency, most respondents operated in a MERO role, managing emergency response and associated communication. A combined total of four respondents focused on planning and communication; two metropolitan respondents dealt with the media, while one rural council employee had a multifunctional position. After an emergency, the priority for most people was recovery and repair operations (67 per cent, n=18), with a combined total of four (15 per cent) concentrating on media and communication responsibilities. It may be that the recovery and repair emphasis partly reflects budget allocations. While 41 per cent of respondents had a budget for emergency communication, 59 per cent did not, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Budget allocation for emergency

Respondents were asked, ‘Could respondents do more before, during and after an emergency?’ Responses to this question were evenly split. Of those who thought there was room to make a greater contribution, most felt that dedicated resources, more training and more funding would facilitate more involvement. Some also thought they could play a more significant part in communication and sharing of information. However, a significant number (n=11, 41 per cent) did not respond to this question. In most cases (n=17, 63 per cent) time, budget or the availability of other necessary resources were identified as barriers to making an additional contribution, although two considered that a lack of understanding or commitment in their local government council constituted an obstacle. One respondent saw the diversity of the local government sector as a barrier in itself: ‘State-based agencies don’t comprehend that the 79 municipal councils are, in fact, 79 independently managed companies in their own right and therefore it is difficult to have the same level of consistency across each municipality as each sees the level of risk differently, and there are huge competing values and expenditure across the sector.’

Respondents were asked, ‘If there was one thing you could change about your, or your team’s involvement in emergencies, what would it be and why?’ There was consensus around the need for dedicated resources, more training with practical exercises and preparation testing, and also around the need for an improved or changed approach to emergencies per se (n=5, 19 per cent in each case). Two respondents pointed to the training offered by the Australian Emergency Management Institute, which includes ‘community engagement and communication’. One metropolitan respondent noted: ‘In general councils need more resources for emergency management – both human and financial’. Another commented that there had been ‘cost shifting from state government to local government’. The theme was repeated by another respondent from a rural council who commented: ‘The role of local government in emergency management needs to be reviewed’. The sentiment was endorsed by another rural respondent who wanted to ‘reduce [our] involvement commensurate with resources as emergencies do impact on the team’s ability to deliver against their normal program’. Two rural respondents wanted emergency response agencies to give them greater responsibility.

For questions related to training, there was a distinct (n=8, 30 per cent) preference for training on clear communication, the use of social media, and community engagement techniques and effects. A rural respondent noted that while there was not necessarily an opportunity to make a greater contribution than at present: ‘We are currently working on improving communication in emergencies, particularly through the use of social media. We are working with four other councils to develop communication protocols across the councils and to develop a communication framework’. The social media topic was picked up by another regional/rural respondent who was interested in training that was focused on how the right social media-based communication could influence ’community psychology’.

One metropolitan respondent wanted training around ‘communicating before, during and after emergencies’. There was recognition of the challenges this might entail, with interest in training on ‘dealing with different sectors of the community, dealing with traumatised…[and] angry people’. In line with this interest, another respondent from a rural council wanted training in ‘handling rumours in an emergency environment’ [because] ‘rumours abound when official information is missing’. There was interest in ‘communication recognised by emergency management specialists as critical to delivering strong performance outcomes’ from another rural respondent, while a rural colleague sought training on ‘emergency management planning, operating and working in a municipal emergency control centre including command, control, co-ordination, roles and responsibilities’. One comment envisaged communication training going two ways: ‘For the most part a large number of communication professionals have a degree in crisis and emergency communication training/experience. Perhaps emergency managers need to be trained in the use of communication and engagement techniques’.

A respondent from a regional council was keen to be trained in ‘how to develop “targeted” communication tools that ensure the message gets through to the “whole” community and how to keep EM (emergency management) in residents’ front-of-mind rather than when an event is under way – but without becoming boring or they just turn the page’. One rural respondent wanted training in several areas—emergency management communication, HR management, time management, and resource management during an emergency incident.

A call for training on the roles and responsibilities of external agencies was well supported (n=7, 26 per cent). In one case, a metropolitan respondent was keen to see a change in ‘knowledge of council’s role in emergencies’. A regional respondent identified ‘understanding by outside agencies of the role of emergency management at local government level’ as a barrier to making a greater contribution to emergency management. Another from a rural council wanted to see ‘better communication inter-agency’. The latter respondent noted that there was a ‘need to ensure that messages put out by other agencies accurately reflect our agency’s role. Too often they get it wrong and cause increased workload’. However, many felt either that they were already adequately trained or gave no answer to this question. Asked for additional comments, two rural respondents called for emergency operations to be simplified. One metropolitan respondent saw a need to ‘clearly define local government’s role in an emergency, what our response is given various situations’.

State government’s role was criticised by a respondent from a local government council encompassing both metropolitan and rural areas—a so-called rural-urban interface council. Replying to the question, ‘If there was one thing you could change about you, or your team’s involvement in emergencies, what would it be and why?’ the respondent indicated ‘greater leadership and direction from State Government, which has abdicated significant responsibility in developing key policies and measures e.g. identification of vulnerable people’. The same respondent was interested in ‘significantly improved warnings policy that is much more timely, more accurate and more blunt—and a clear authority [sic] of who will deliver the message’. Continuing, the respondent wanted ‘a model…of what communication need to be made, when and by whom. Thus, when the Premier helicopters in, they could have a list of speaking points on which they could make announcements and not make policy on the run’.

Table 1 shows the responses to the question ‘If you were to be given training in emergency management and associated communication, what topics do you think it should cover?’ How to best use social media and the most effective ways of working with external agencies are clearly seen as the most important areas to cover in future training.

Table 1. Training topics

|

Metro area |

Rural area |

COMBINED |

|||

|

Interaction with External Parties/MECC |

3 |

Agency roles/external responsibilities |

4 |

7 |

26% |

|

Communication/Social Media |

2 |

Communication/Social Media/Engagement Techniques & Effects |

6 |

8 |

30% |

|

Incident/Consequence Management |

2 |

2 |

7% |

||

|

Various topics |

2 |

2 |

7% |

||

|

Nothing/No Answer |

3 |

None/No Answer/Already trained |

5 |

8 |

30% |

This survey has some obvious limitations. The sample was Victoria-based rather than national and therefore the findings presented may differ elsewhere. Responses came from 27 of 79 local government councils and may not capture behaviour and needs in the councils that did not participate. While the original aim was to explore the activity of professional communicators, MEROs constituted the largest group of respondents and therefore the results point to different perspectives and needs than those expected.

As emergency managers, MEROs are able to call in specific communication support they need (P. Fitz, personal communication, 18 October, 2012). However, the responses to the survey indicate that at least some MEROs do not consider that enough (or they do not have communication assistance available, or possibly they are unaware of what communication help they are able to call on). The improvements they seek are not merely a matter of increased personal knowledge of communication but also enhanced inter-agency communication and more effective communication to communities. Further, there is a need for clarification of communication roles and responsibilities, both locally and in relation to other agencies, such as the state and territory governments. These findings were not envisaged, as care had been taken to identify and invite participation from council staff with specific communication responsibilities. The fact that 63 per cent of participants came from MEROs may simply mean that the ‘emergency’ focus of the survey resulted in it being passed to the staff most readily identified with the emergency portfolio. The results however, do indicate both a need for action to improve communication at local government level and potential for further research. This might focus on why is it that MEROs want more communication training. Is it simply that they wish to improve their personal effectiveness or does their desire indicate a lack of confidence in communication resources available to them? How successfully are MEROs working with dedicated council communication staff? How confident are those staff in the value of their contribution to emergency communication? How specifically does the management of emergency communication differ between rural and urban local authorities? These and related questions demand answers and represent an agenda for future inquiry. Research might usefully focus initially on the relationships between MEROs and professional communicators in emergency management contexts.

Alexander, D 2005, Towards the development of a standard in emergency planning, Disaster Prevention and Management, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 158-175.

Australian Local Government Association, n.d., Emergency management: national approach. At: http://alga.asn.au/?ID=65 [21 October 2012].

Boin, A & t’Hart, P 2010, Organising for effective emergency management: lessons from research, The Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 357-37.

Caiden, G.E 1961, The neglect of public relations in Australian public administration, The Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 20, issue 4, December, pp. 331-339.

Hilliard, M. 2000. Public Crisis Management: How and Why Organizations Work Together to Solve Society’s Most Threatening Problems. Lincoln: Writer’s Club Press. Cited in Boin, A & t’Hart, P 2010, Organising for effective emergency management: lessons from research, The Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 357-37.

Horsley, J. S., Liu, B. F., & Levenshus, A. B. 2010. Comparisons of US Government communication practices: Expanding the government communication decision wheel. Communication Theory, 20, 269-295.

Howard, A.E 2012, Connecting with communities: how local government is using social media to engage with citizens. ANZSOG Institute for Governance at the University of Canberra and Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government. [21 October 2012].

Kapucu, N 2008, Collaborative emergency management: better community organising, better public preparedness and response, Disasters, June, vol. 32, no. 2, pp.239-62.

Killingsworth, C 2009, Municipal government communication: the case of local government communication, The McMaster Journal of Communication, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 61-79.

Leadbeater, A 2010, Speaking as One: The Joint Provision of Public Information in Emergencies, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 25, no. 3, July 2010, pp. 22-30. [18 October 2012].

Liu, B & Levenshus, A 2010, Public relations professonals’ perspectives on the communication challenges and opportunities they face in the US public sector’, PRism, vol. 7, no.1, pp. 1-13. Morris, R 2012, Community engagement in rural-remote and indigenous local government. Report for the Australian Centre of Excellence in Local Government. [21 October 2012].

Simmons, P & Small, F 2012, Politics, promotion and pavements: professional communication in Australian local government. Paper prepared for the i-COME’12 conference, Penang, Malaysia, 1-3 November, 2012.

The author gratefully acknowledges the not-for-profit research and networking organisation, Emergency Management and Public Affairs (EMPA), for the funding of this research. In particular he acknowledges the support of EMPA’s research and development committee. The Municipal Association of Victoria also provided help in accessing council contact details.

Dr Chris Galloway is a senior lecturer in public relations, previously at Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne but now at Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand. His research interests include issues, emergency, crisis and risk communication.