By Graeme McColl, Emergency Management Advisor (Retd)

Frequent media reports and many reviews (two cited in this paper) of health responses to major emergencies stress the failures of control and co-ordination and the lack of application of the lessons learnt to the next major disaster where a health response is required.

One of the repeated criticisms following any review of health response to a major emergency is the lack of control and co-ordination of the responders and resources.1 This was most apparent in the January 2010 response to the massive earthquake in Haiti. Apart from the many media reports (not always accurate) one of the first reports on the situation was the Haiti Disaster Tourism – A Medical Shame (Van Hoving et al., 2010). This provided valuable insights into the ‘provision’ of unrequired and inappropriate personnel and aid.

The report highlighted the problems with unsolicited and unco-ordinated aid.

“Sometimes the responders are poorly suited to help, with little or no experience in international relief, poor understanding of the local culture, and usually have no relationship with either the local agencies or the affected population. This influx phenomenon has been described as ‘disaster tourism’ or ‘parachuting’. This has an adverse impact on relief efforts, and may dim local receptiveness to foreign help” (Van Hoving et al., 2010).

Fortunately the paper was published in June 2010, prior to the series of earthquakes that rocked Christchurch, New Zealand, in September 2010 and February 2011. The problems highlighted were seen as something that must be avoided in the health response co-ordinated by the Canterbury District Health Board (CDHB) and supported by the Ministry of Health. In a small way the health response in the aftermath of earthquakes in Christchurch took heed of the lessons and recommendations and produced positive experiences that could be developed for global consideration.

New Zealand, like most countries, has a plan for the health response to major emergencies. For example health professionals must receive approval and be accreditated from respective NZ colleges and the Ministry of Health. The procedure provides the control required over those arriving with good intentions but who are not suitable or required. Approvals can be streamlined for an emergency situation.

The New Zealand Ministry of Health National Health Emergency Plan (NHEP) provides for District Health Boards to control and co-ordinate the overall health response within their regions of responsibility with the Ministry taking responsibility for national support and co-ordination.

The Ministry of Health and CDHB took responsibility for the ongoing provision of health services as well as the health response required for the aftermath of the earthquakes. Nationally, overall control and co-ordination was the responsibility of the Ministry for Civil Defence & Emergency Management (MCDEM). Liaison between the Ministry of Health and the Civil Defence Emergency Management organisations (CDEM) was established at national and local levels.

These structures ensured that control and co-ordination was established and that responsibilities and functions were clearly defined. They also met terms contained in the UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 which acknowledges that governments have primary responsibility for organising humanitarian assistance following a major emergency (United Nations, 1991). The authority for all health issues should remain with the government body responsible for health provision in the affected country.

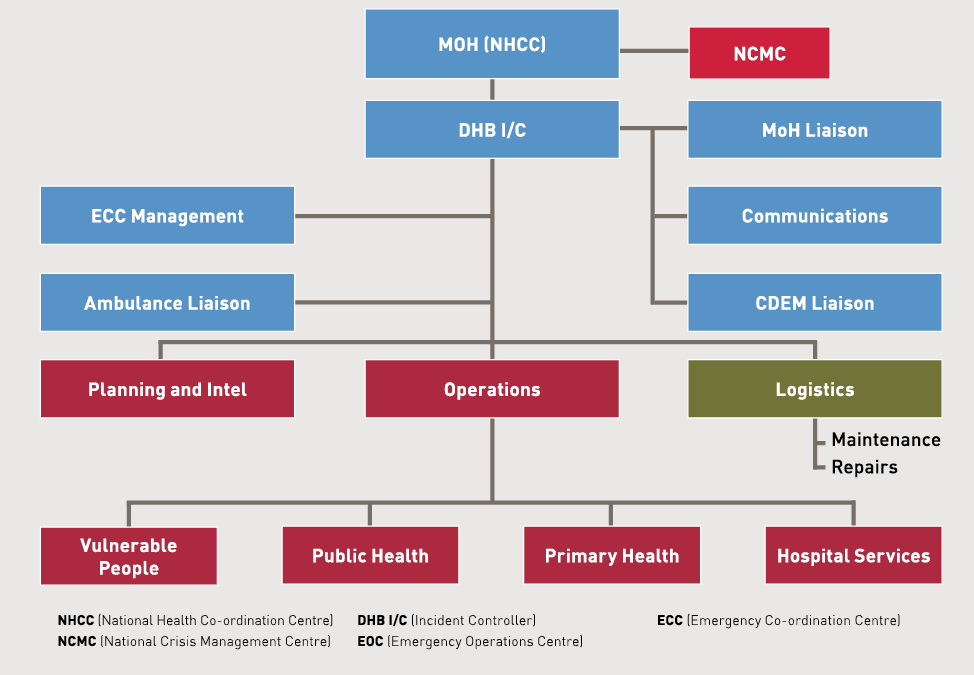

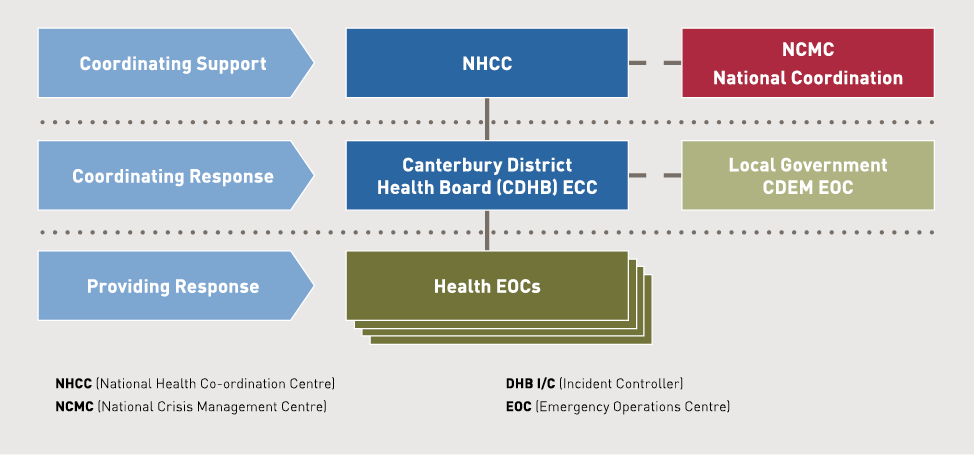

Figures 1 and 2 show the organisational structure for the health response to the NZ earthquakes.

Figure 1. Health emergency response organisational structure.

Figure 2. Functions structure and links to Civil Defence & Emergency Management.

However, in the NZ earthquake response, these organisational arrangements and responsibilities could not guarantee that inappropriate or unsolicited resources and responses would be controlled. A centralised approach to control and co-ordination of resources was required. To enable this, the movement of patients locally and nationally was included.

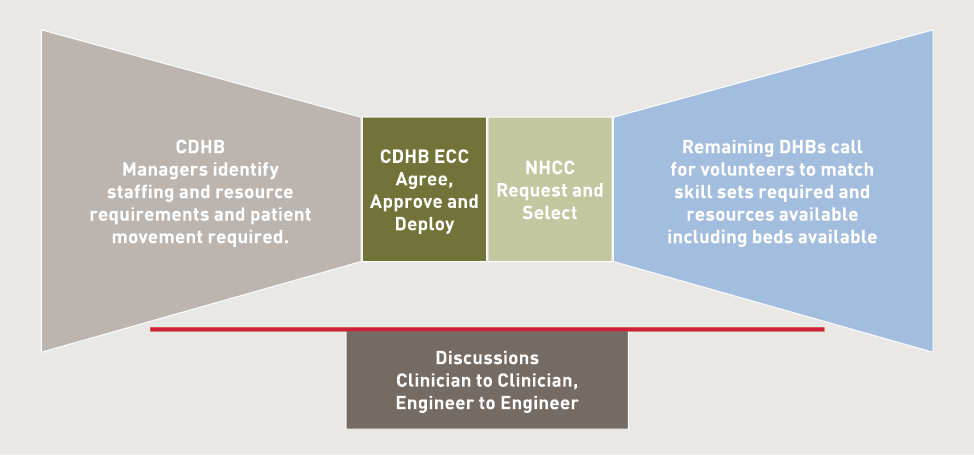

Thorough assessment of needs was required from managers. This included investigating the altered use of their own resources to meet new priorities. Their respective needs, if not met, had to be prioritised and specifically described including identification of skills required, shifts to be covered, and how long resources were required. These details were sent to the CDHB ECC, that would check and agree with overall resource availability and approve for action.

No request by any manager or staff was made to any outside source, nor were ‘self presenting’ volunteers accepted without agreement and appropriate checking of credentials. This did not preclude clinicians discussing patient needs with clinicians elsewhere prior to transfer, or engineers discussing plant and building issues before support action. Once discussions had taken place the approval process of the CDHB was to be followed.

Initially, the flow of information was achieved by emailing Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Problems arose when DHBs responded to requests for assistance. When a DHB received a request they would assess their ability to supply or respond. When they had made arrangements to meet the request and advised staff or allocated resources some found their acknowledgement had been slower than other DHBs and offers for assistance had been accepted and arrangements made. Naturally, frustrations arose and much work around reallocation of staff and resources was wasted.

The CDHB responded and introduced a more effective, user-friendly and accurate means of requesting resources and communicating. This was achieved quickly with the use of Google Docs, where web-based documents could be centrally accessed by authorised personnel. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Flow chart of the CDHB resource control and co-ordination process.

The assessment and requesting process remained the same and the requests were still entered into a spreadsheet, but now everyone had a single source of information and access to the current status of requests.

Google Docs proved to be a valuable tool as it enabled users, located in different geographical areas, to access the same document at the same time. The facility allows approved users to simultaneously edit, change, and update the same document.

Colour coding was used to highlight the progress of requests, as shown in Figure 4. Every request received an immediate colour code as each action commenced. This meant that time was not wasted by supported DHBs by others responding to the same request. Over 300 requests, together with the responses for staffing, were managed in this way after its introduction in April following the February 2011 earthquake.

Figure 4. Request for resources spreadsheet.

Colour |

Coded meaning |

|---|---|

Key: WebEOC2 = Ministry of Health Emergency Management Information System (EMIS). VHP = Visiting Health Professional. |

|

White |

There is a vacancy (position is still being advertised on WebEOC with other DHBs). |

Green |

NHCC is working on it (have a placement just waiting to confirm VHP name, contact details, flights and accommodation requirements). |

Orange |

Christchurch EOC is working on request. Need to book accommodation, phone and confirm, email and inform sponsor and HR advisor. |

Yellow |

VHP is all booked and confirmed |

Figure 5 provides an example of the spreadsheet fields and the cell content. This example relates to the requests for staffing and skills. Similar systems were also in place for patient movements and supply requests.

Figure 5. Example of spreadsheet fields.

Ref No |

Request Date |

Status |

Position requested |

Facility |

Location |

Sponsor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

211 |

3 Mar 2011 |

Requested |

Social Worker |

Mental Health Unit |

Hillmorton Hospital |

Gordon Woodstock |

Sponsor Contact |

Required From |

Shift(s) |

Duties |

Accommodation |

Actioned By DHB |

ETC> |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mob xxxx xxx xxx |

7 March 2011 |

The relocation of staff to Christchurch commenced only when arrangements were in place for them to be met at the airport, given an induction to their duties, provided with accommodation and local travel arrangements. This system and procedures worked well and control was maintained allowing for proper co-ordination.

Some examples of the controls exercised were:

The Ministry of Health has added health applications to these procedures to incorporate the online, real-time requests and responses to resource needs for future major emergencies in New Zealand. The MCDEM is also implementing a national EMIS system.

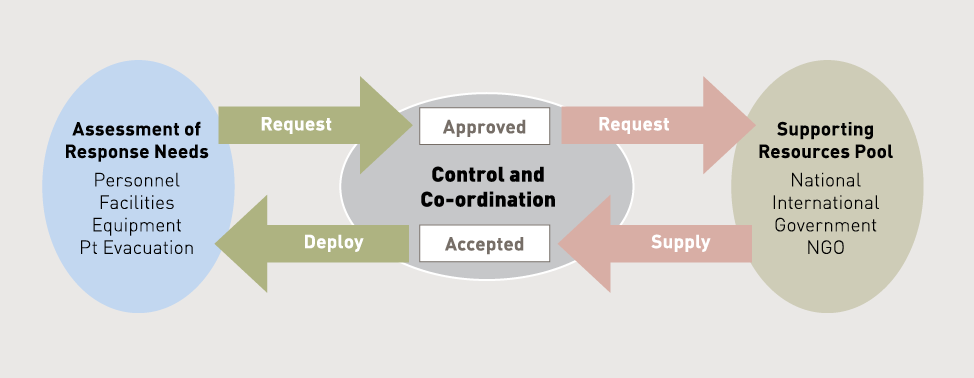

The CDHB resource control and co-ordination model worked for the situation following the Christchurch earthquakes and the lessons learnt from responses to major international sudden onset disasters were applied. The development of the CDHB model for international use in control and co-ordination could be evolved as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Flow chart of CDHB Model for international application.

It is necessary to take the experiences from the New Zealand earthquakes and promote them in the international arena as it is clear that positive lessons could be absorbed to ensure the chaos of past responses is not repeated. Proof that positive control and co-ordination experiences need to be publicised and shared are apparent from the recent Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) publication of a full review of the health response to Haiti (de Ville de Goyet, C et al., 2010). The findings in this comprehensive publication support and expand the findings of Van Hoving (2010).

In the publication’s foreword, Mirta Roses Periago, Director of the PAHO, comments:

“If the impact was unprecedented, the organisation of the response was not. It followed the same chaotic pattern as in past disasters. Information was scare, decisions were often not evidence-based, and overall sectoral coordination presented serious shortcomings. Management gaps noted in past crises were repeated and amplified in Haiti. The humanitarian community failed to put into practice the lessons learnt” (de Ville de Goyet, C et al., 2010).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has taken heed and set a priority resulting from the Haitian experiences. A Foreign Medical Team (FMT) working group was formed and is actively meeting and seeking agreement to ensure there is control and co-ordination during future responses. This work is based on actual experiences not only in Haiti but also Aceh, Pakistan and Rwanda.

The group has made the following recommendations and is working on the implementation.

“The Cuba (late 2010) meeting recommended a Foreign Medical Team (FMT) working group be set-up to guide and monitor activities related to the development of an international register for FMT provider organizations following a sudden-onset disaster, with the overall aims of:

a. improving FMT’s adherence to international core standards,

b. ensuring that these FMTs respond to identified needs that cannot be met nationally” (Ibid).

At a meeting in Geneva in December 2011 the following goals were agreed.

The push is to bring control by approving FMTs as responders to major emergencies and eliminating the sudden rush of ‘feel good’ responders who have failed to respond in an appropriate manner in the past. Arguably, there could be difficulty with some accepting such approval and the requirements on control and co-ordination it would bring. This is more so with the proliferation of responders in recent years. For example:

“In Banda Aceh, Indonesia following the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2005, 180 agencies (representing all agencies (not just health)) registered with the UN.

In Port au Prince, (Haiti) the proliferation of international organisations was far greater than Banda Aceh. In the health sector alone, 390 agencies, mostly international registered with the external coordinating mechanism (Health Cluster). Many more health actors did not register.” (Ibid).

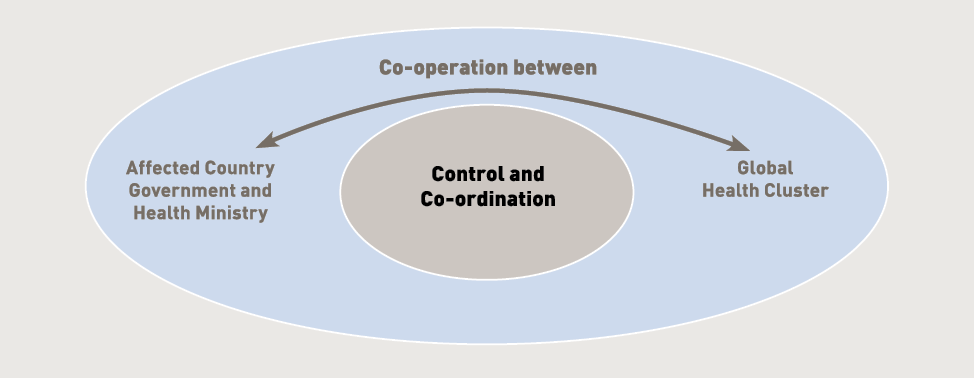

Clearly there must be co-operation between governance in the affected country and the global health cluster to bring control and co-ordination to the response. This ensures that chaotic situations of the past remain there. While each responding organisation, either national or global, has control and co-ordination of their own resources the overall relief effort is, and must be, controlled by the national government and not the global community.

Figure 7 shows the addition of the element of co-operation to the flow chart in Figure 6. It provides a model suitable for international use. Agreement to co-operate must be an essential requirement in any developments by the WHO FMT working group in the process to ‘approve’ FMTs.

Figure 7. Need for co-operation to ensure control and co-ordination.

The Haiti situation, depicted by de Ville de Goyet (2010) must be corrected.

“All profess to be willing to coordinate with others. Few accept being coordinated. Many operational partners, while decrying the vacuum of authority as a major impediment to effective relief, in fact see it as convenient” (Ibid).

This is hardly the ‘harmonious adjustment’ from the meaning of co-ordination provided at the start of this paper.

Control and co-ordination as mandated by the UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 achieves an organised and appropriate humanitarian response to the health requirements following a major emergency, provided there is co-operation between all agencies involved.

Many papers and editorials have been produced outlining the problems and the lessons to be learnt to avoid previous mistakes.

The initiatives of the WHO FMT working group in developing approval for FMTs requires acceptance and support to ensure that chaotic situations of the past are avoided. The aim must remain to provide a proper, appropriate and sustained humanitarian response to affected communities.

de Ville de Goyet, C., Sarmiento, J.P., Grunewald, F., (2010) Health Response to the earthquake in Haiti, January 2010. Pan American Health Organization.

Norton I, The Foreign Medical Team Working Group, report on progress, WADEM Oceania Chapter Newsletter Feb-Mar 2012, p 7 www.wadem.org link publications Oceania Newsletter. Accessed 10 May 2012

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182 (1991). http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/46/a46r182.htm. Accessed 9 May 2012.

Van Hoving D. J., Wallis L.A., Docrat F., De Vries S., Haiti Disaster Tourism- A Medical Shame, Journal of Pre-Hospital and Disaster Medicine, Vol 25 No 3 May-June 2010: p201-202

Graeme McColl retired in late 2011, after more than 15 years in health emergency management covering New Zealand’s South Island. In the last four years, Graeme was employed by the Ministry of Health as an Emergency Management Advisor. He filled key response roles for the Ministry of Health during the Swine Flu pandemic in 2009 and the Pacific tsunami the same year. Following the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011 he served as a liaison between Canterbury District Health Board and the Ministry of Health during the response.

Graeme is currently the President of the Oceania Chapter of the World Association for Disaster and Emergency Medicine (WADEM), a member of the Editorial Board for the WADEM Prehospital and Disaster Medicine Journal and is the Editor/Co-ordinator of the Oceania Chapter Newsletter.

1. For the purposes of this paper control and co-ordination are defined as: Control - to exercise authority or dominating influence over. Co-ordination - state of being co-ordinate, harmonious adjustment or organisation. (The Free Dictionary, Fartex, www.thefreedictionary/ accessed 31 May 2012).

2. WebEOC, V7.1. Product of ESI Ltd.