This paper outlines how a large Public Information Management (PIM) team was pulled together at the time of the earthquake response. It considers the unfolding events and the PIM team’s tactics and makes recommendations for the management of public information in future large-scale emergencies. Findings are based on an analysis of PIM activities and were presented at the Emergency Management and Public Affairs (EMPA) Conference in May 2011.

“Communication is the critical thing and if you do not do it right you will be judged to have failed, regardless of what else you do with your fire trucks and your response.”1

Bruce Esplin, the former Emergency Services Commissioner for Victoria, made this observation when he addressed emergency communicators in 2009 after the Black Saturday bushfires.

Correctly managing public information is a key element of managing an emergency. Increasing access to, and use of, social media, web-based journalism and the 24/7 news cycle have raised public expectations of immediate access to information. Communities no longer accept an attitude of: “trust us, we know what we’re doing.”

The response to the Christchurch earthquake in February 2011 brought together the largest PIM team ever assembled in New Zealand. Tasked with developing and communicating critical public safety messages, the team’s responsibilities included media liaison and press conferences, website updates and social media content and monitoring, community engagement, stakeholder relations, staffing the public call centre, hosting VIPs, advertising, publications, inter-agency communications, and keeping elected members informed.

The enormity of the tasks faced both in the extent of communication and length of time the response ran, led the National Controller, John Hamilton, to concede that he had “grossly underestimated how much time and effort was required to manage the media” and the amount of work required by the public information team to cover off on the multiple channels used to reach the community2. In his view, public information management “came of age” during the earthquake response and he concluded that “The effort by a raft of people paid off and the result was good.”

Image: Jason Dawson

Media team members of the Public Information Management section, 28 February – Dave Miller dealing with a media query while Mayor Bob Parker (left) checks his daily briefing notes.

It's impossible to manage public information successfully in a serious and escalating situation with the resources used in routine events.

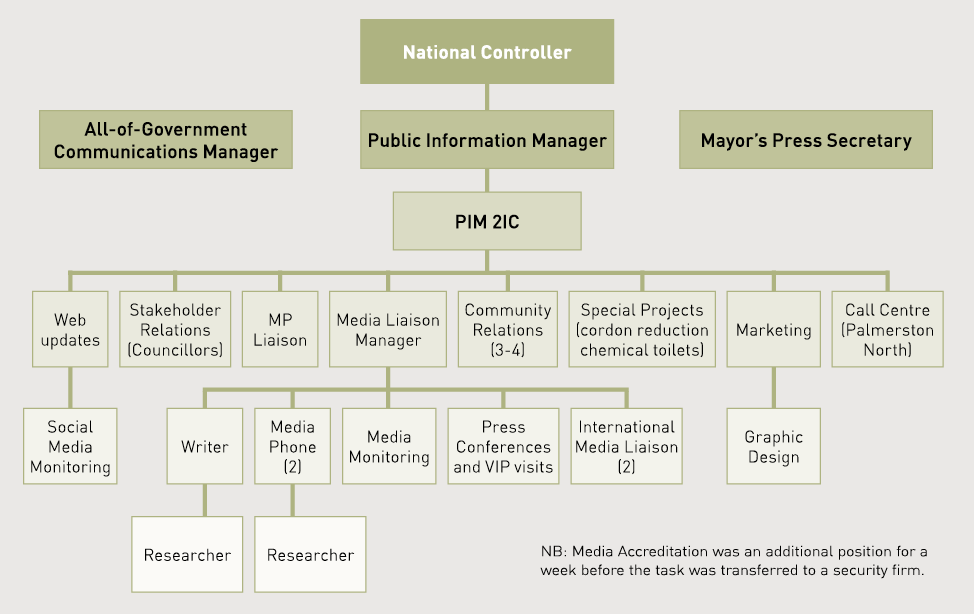

The Canterbury Civil Defence and Christchurch City Council emergency management units both had small PIM teams which worked independently. Following the quake, on Friday 25 February, the National Controller combined the groups and the PIM teams were brought together in a new structure with over 22 positions covering a range of responsibilities (see Figure 1). Each shift had a Public Information Manager, a Media Manager and media team members, a webmaster, and social media monitor. Another six positions covered two shifts while the remainder worked a daytime shift. Over 45 people were needed each 24 hours.

Figure 1. Christchurch Earthquake Response, Public Information Structure as at mid March-2011.

On day two a new position of Assistant PIM was created to direct and manage the team. The Mayor’s press secretary was also part of the team but did not report to the PIM. An additional position was created to accredit attending media, but this task was later delegated to a security firm. As the response continued, team members were seconded to work with other sections to co-ordinate the messaging of specific issues. Some roles remained vacant due to lack of suitable personnel. VIP visits were organised by the PIM team, the Mayor’s office, the Controller’s team, or from staff in Wellington.

While doctrine required all PIM team members to be trained in the civil defence system, this proved neither feasible nor necessary. Some staff were unavailable because of the earthquake’s impact on their families and homes so other trained personnel were required. Local body and government agency staff from other regions known to have the right skills and experience, Council librarians, archivists, webmasters and designers, and a handful of contractors from PR agencies, came together to take up roles and fill the rosters.

Recommendations:

1.1 Be clear about the skills, attributes and experience required when recruiting.

1.2 Fill key leadership roles with staff trained in emergency communications. Draw on people with appropriate skills who can fill a role within the team.

1.3 Have clear lines of responsibility within the team.

Only the Controller could authorise the release of information. If he was unavailable no-one else had delegated authority and the release of information could be delayed for up to an hour.

Media updates were developed from briefings, press conferences and planning sitreps, which were checked and signed by the Controller. Emergency management response organisations can be on the back foot when authenticating and releasing information. While news media have protocols for verifying the details of what they broadcast or publish, in a fast-moving event they report what they see and hear. Social media channels have no such constraints and anyone with a smartphone can send what they see or hear to an expanding audience in seconds.

Recommendations:

2.1 Maintain rigorous checking and sign-off procedures for the release of all information.

2.2 Ensure the authority to approve the release of information does not reside with one person.

2.3 Develop protocols so information provided at a press conference or public meeting is based on authorised briefing notes that can be used as the basis of a media release, bulletin, update or talking points without a fresh approval process.

Recognise the different needs of residents in different localities and those who have been impacted in different ways. Tell them what they need to know.

At the 2006 census, 348,435 people lived in Christchurch making it New Zealand’s second largest city. While the whole city was affected by the earthquake, suburbs were impacted in different ways and to differing extents. Media coverage focused initially on the central business area where the most deaths and casualties occurred and many buildings collapsed. Yet the significant impact on most citizens was in their homes. Land liquefaction, structural damage, loss of power, water and sewerage systems, twisted roads and broken bridges were worst in the suburbs nearest the sea, with hill communities also impacted by landslides and rockfalls. Neighbourhoods which escaped widespread damage experienced pockets of destruction. Indeed the whole of Christchurch’s population was affected by the fragile water, sewerage and power systems, congested roads, and constant aftershocks.

Initial message design was general in nature, for example, “check on your family and neighbours”, “boil the water”, “how to make an emergency toilet”, “where to access welfare centres and water tankers”. Other messages were targeted at particular audiences - residents of specific suburbs, building owners, beneficiaries, householders needing chemical toilets.

The PIM team used a variety of channels to reach residents, none of which would have been adequate alone. They included:

Facebook, Twitter and other social media were monitored and answered 24/7. Trending issues were identified and reported to the Planning/Intelligence team. Social media, by its very nature, is easier to monitor and evaluate and response times can be immediate. These channels proved an effective way to counter rumours and correct misinformation.

The city’s newspaper, The Press, was delivered to most suburbs throughout the emergency. The PIM team placed full page advertisements in The Press almost daily with details of where to get help, road closures, the location of water tankers and other key information.

Residents who stayed in their homes situated inside the cordoned-off central city were isolated from official sources of information. They had no power, water or sewerage, and found it increasingly difficult to get through the cordons as access was tightened and a system of passes was introduced. As this community was not officially acknowledged, no effective way was identified at the time to get information to these residents.

The PIM team was also responsible for communicating with the estimated 63,000 residents who had been evacuated or had chosen to leave Christchurch. Messages were developed to help evacuees understand what was happening to their properties while they were away, where they could get help and support, and to advise them on practical matters when they returned. These messages were published in advertisements in the daily and community newspapers, in the recovery tabloid delivered to all households in March, via fliers, on the website, and by mass text messages.

Image: Michele Poole

Civil Defence used mass text messages like this

to reach Christchurch residents from week two ofthe emergency.

Image: Jason Dawson

The Public Information Section monitored social media, and projected tweets on the wall so team members could see what was trending.

Recommendations:

3.1 Identify discrete communities and develop strategies for communicating to each.

3.2 If a daily newspaper is maintaining deliveries to impacted areas, negotiate to increase the print run and deliver to every household.

The internet is useless to people who have no power or who don't have internet access.

The website was a very effective means of providing complex information on multiple topics, but only to those who could access it. The day after the earthquake electricity had been restored to 50 per cent of the city. By day four 42,000 customers were still without power.5 Residents in the eastern suburbs were without power for days and for 550 homes, it was weeks.6 Aside from those without power, an estimated 30 per cent of households had no access to the internet at home.7 Those without access who were constantly told they could “get more information on-line at …” became frustrated and angry.

Recommendations:

4.1 Use multiple channels to provide information. Avoid over-reliance on the internet.

4.2 Update website content as the emergency response evolves.

Radio is highly effective for reaching a mass audience in the immediate aftermath of an emergency.

Broadcast media played a critical role in communicating the scale of the damage and the immediate impacts after the earthquake. Commercial radio stations gave updates about casualties, damage, road closures and practical advice, while Radio New Zealand broadcast live reports.

Image: Jason Dawson

Controller John Hamilton being interviewed during a media trip inside the red zone.

Commercial stations continued to broadcast civil defence messages to Christchurch residents in the days following the earthquake. As normal programming resumed, the Christchurch City Council paid for civil defence messages.

In week two, Southland community broadcaster, Chris Diack, relocated his mobile studio to Christchurch and set up a small station in the eastern suburbs. Although it had limited range and the listenership wasn’t measured, it provided information targeted at local residents.

Recommendations:

5.1 Educate communities to listen to local radio stations during emergencies.

5.2 Develop relationships with broadcasters and establish procedures for providing authenticated emergency messages.

Acknowledge the role media organisations play and make it as easy as possible for them to communicate messages. Media perception of the way the emergency is managed will influence the community's level of confidence in the response.

Physical conditions for journalists covering the Christchurch earthquake were difficult. The Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) was inside the central city cordon. Before the official media accreditation system was implemented journalists had to negotiate their way through the cordons each day and wait for a press conference or waylay emergency personnel. There was no shelter, no access to food or water inside the cordon, and the only amenity was the EOC portaloos. After a week, a marquee was set up as a media centre.

Image: Michele Poole

International and local media clustered for a stand-up press conference two days after the earthquake.

Police arranged the first media bus trip inside the cordon on day three. Once the expanded PIM team became operational, a media liaison officer was dedicated to the journalists camped outside the EOC. By 3 March there were 600 accredited journalists on site.8 Two press conferences were held each day, one or two daily bus trips through the CBD were organised, and there were regular opportunities to film or interview Urban Search and Rescue representatives and emergency services personnel.

Most international media left on 11 March following the earthquake and tsunami in Japan. NZ and Australian journalists maintained a constant presence for weeks.

Recommendations:

6.1 Consider the physical needs of attending media as well as those providing coverage elsewhere.

6.2 Implement media accreditation immediately.

6.3 Set up a media centre close to the EOC.

6.4 Identify photo opportunities and arrange access to restricted areas where possible. Be open about the reasons for denying access or requiring pooled footage.

Some people will be too traumatised to hear or understand official messages.

All information put out by the PIM team during the earthquake response was on the website. Basic messages were reiterated daily in newspaper advertisements, on radio and in media updates. As the response evolved, the key messages changed. People who didn’t have internet access or a battery-powered radio, or who didn’t receive a daily paper, or who had left Christchurch and returned later, missed some of the information provided at the beginning of the response. Some were too shaken and emotionally fragile to understand or retain what they were told. Only personal visits would have proven effective for the most traumatised residents who were coping with land liquefaction, damaged homes and possessions, sudden unemployment, disrupted schooling, no electricity, no water, and no toilet facilities.

Recommendation:

7.1 Liaise with welfare agencies to ensure field staff are communicating key messages and obtain feedback about what they are encountering in the community.

Christchurch has New Zealand’s largest community of deaf people and a large immigrant and refugee population. To reach these groups a Sign Language interpreter stood beside every speaker at press conferences and information fliers were translated into the most commonly spoken languages.

Recommendations:

8.1 Identify non-English speakers in the community and ways to help them receive messages.

8.2 Identify potential interpreters.

Communication with the business sector began badly. The initial priority was to identify and contact building owners, rather than the tenants, in relation to demolition or ‘deconstruction’ of their property to prevent further damage to adjacent structures or provide safe access routes. The extent of the damage and the danger level in the inner city meant it was weeks before many businesspeople were allowed even brief access to their premises.

Access to the CBD was controlled at various stages by a mix of personnel from the NZ Defence Force and Army Reserve, the Singapore Army, NZ and Australian Police. Such a combination meant that consistency in the rules governing access was lacking and business owners were frustrated at being refused access to retrieve critical records so they could restart in temporary premises. By mid-March several protests took place outside the EOC, which prompted a meeting between Civil Defence and the business community. Although the Canterbury Employers Chamber of Commerce had been meeting the Controller’s representatives regularly, information had not reached hundreds of small business owners. The PIM structure had provided for an external stakeholder relations position, but this was not filled until week three, and then only for MP liaison. While social media monitoring identified the growing frustration among the business community and the media coverage of disgruntled business owners was increasing, it was not given priority as an area needing special attention.

Virtually the whole of the Central Business District was cordoned off as the no-go ‘Red Zone’ because of collapsed or compromised buildings. The rest of the inner city was divided into zones and opened progressively.

Recommendations:

9.1 Be proactive. Identify affected groups and set up direct communication with them.

9.2 Test arrangements for passing messages through representatives.

In a crisis, communities look to elected members for leadership and reassurance.

Mayors, councillors and Members of Parliament play an important but ill-defined role during emergency responses. While focus is on managing the emergency, Mayors can be briefed for media appearances and public meetings to reassure the community. Christchurch Mayor Bob Parker was acknowledged as the face and voice of the earthquake response in September 2010, and in February 2011 he filled the same role. From 25 February, he and the National Controller spoke at every press conference. The Controller would speak first about the response and the Mayor would cover ‘hearts and minds’ issues. Outside the press conferences the Mayor handled the bulk of the media interviews.

It is important that response personnel in the EOC are focussed on their roles. Access to the EOC by others can cause considerable distraction. During the response some local government Councillors and MPs did gain access to the EOC as they felt their requests for information or action were not getting a response. The PIM structure provided for two stakeholder liaison positions dedicated to elected members, but one was not filled for three weeks and the other proved inadequate.

Recommendations:

10.1 Negotiate roles that elected members can play during the response. Councillors, community board members and MPs are legitimate representatives of the community. They can provide reassurance, communicate accurate messages and provide valuable feedback.

10.2 Brief Mayors before media and community appearances.

10.3 Task a PIM team member with elected member liaison.

10.4 Establish consistent and agreed rules about access to the EOC.

Image: Neil Macbeth / Christchurch City Council

Christchurch Mayor Bob Parker at the first stand-up press conference after the earthquake on 22 February.

As well as Civil Defence, a plethora of other agencies were working on the earthquake response, each putting out its own messages. The All-of-Government Communications Manager (AOGCM) convened a daily meeting of the communication managers from all the participating agencies to share information and align messaging.

Recommendation:

11.1 Liaise closely with communication managers from other agencies involved in the emergency response but outside the CDEM umbrella to avoid conflicting messaging and public confusion about roles and responsibilities.

Nightshift is not the right time for strategic planning!

A recognised shortfall of the PIM response was that it was reactive. Essential messaging was done well in the critical phase but there was no strategic communication planning.

Several factors contributed to this:

Recommendations:

12.1 Identify and designate one person as the senior Public Information Manager.

12.2 Task an experienced PIM to develop / review strategic or longer-term plans for each activity. Align plans to the Controller’s critical priorities and review them to respond to emerging issues.

12.3 Hold a PIM / 2IC meeting regularly to discuss priorities and strategic direction, resolve conflicts and agree on the approach to emerging issues.

In a short, sharp event, people can cope with working long hours. In a long-running response, rostering has to be carefully managed.

In Christchurch, the PIM team’s rosters were aligned with other core functions in the EOC. There were three shifts working 7am – 3pm, 3pm – 11pm and 11pm – 7am. This resulted in too many handovers and a significant demand for staff. However, the Controller’s team worked 12-hour shifts and the Controller worked 16-18 hour days. On reflection it would have been more efficient and effective for the PIM, and arguably the Media Manager, to work 12 hour shifts. This would have improved continuity, required fewer handovers, enabled a better working relationship to develop with the Controller, and freed up a PIM to take responsibility for strategic planning.

Initially there was no difficulty finding people to work in the PIM team – it just took time to get some of them to Christchurch. By the end of the first fortnight, resources were becoming scarce and the earthquake response was still running 24/7. Staff from Christchurch City Council and Environment Canterbury who were filling key roles in the PIM team were facing pressure to resume their normal responsibilities. There was a growing demand to bring in people from other organisations or regions to fill team roles.

Recommendations:

13.1 Be aware of people who consider themselves indispensable. Exhaustion is the enemy of clear thinking.

13.2 Ensure seconded staff do not have a simultaneous commitment to their own work as well as the response team. Resist pressure for local staff to return to their pre-emergency roles while they are still needed in the EOC.

13.3 Roster the PIM, the 2IC and the Media Manager for 12 hour shifts.

The findings of a comprehensive review of the Christchurch earthquake response were released on 5 October 2012. Reviewers concluded that:

Independent to this review, the Canterbury CDEM Group and the Christchurch City Council have organised a forum to discuss public information management in the earthquake response. The conclusions of this forum and the overall review will influence public information management in future large-scale emergencies.

Michele Poole is the Public Information Manager of Emergency Management Southland, the local government agency responsible for emergency planning and response in the southernmost region of New Zealand. She was deployed to Christchurch three times between 24 February and 21 March 2011 as one of the initial four Public Information Managers. She is the first person to be accredited as an Emergency Public Information Officer by Emergency Media and Public Affairs.

1. Bruce Esplin, EMPA Conference, May 2009.

2. John Hamilton, presentation to the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Conference, Wellington, 28 February 2012.

3. Christchurch Response Centre SITREP #23, 20 March 2011. 1.4 million hits by the end of the first month.

4. Ibid. Twitter – 2025 followers by 16 March and Facebook – 897,227 post views after 1 month.

5. National Crisis Management Centre SITREP #10, 26 February 2011.

6. Orion, quoted in http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/christchurch-earthquake/4764928/Return-of-Christchurch-earthquake-evacuees-to-stretch-service.

7. 2006 census figures on internet access (the 2011 census was cancelled because of the earthquake), cited in http://www.ccc.govt.nz/cityleisure/statsfacts/census/familyandhouseholds.aspx.

8. Christchurch Response Centre SITREP #6, 3 March 2011.