Submitted: 24 February 2017. Accepted: 17 March 2017.

Since the 2009 Black Saturday fires in Victoria, there has been a fundamental shift in policy for fire management and response. This includes a focus on empowering communities through knowledge of risk. The National Strategy for Disaster Resilience states:

The National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management noted the frequent complacency of communities before major bushfire events (Ellis, Kanowski & Whelan 2004). The relatively low levels of bushfire risk mitigation actions by at-risk householders is a key issue (McLennan, Paton & Wright 2015), with a consequent need for agencies and communities to develop new, community-based approaches. The policy of shared responsibility requires active community engagement and empowerment, encouraging people to identify their own risks and to be prepared for bushfire. Dimensions of preparedness include awareness, understanding, planning, physical preparation and psychological readiness.

Risk education therefore needs to reinforce values of personal responsibility and risk acceptance. Co-construction or shared understanding of risk is one of the guiding principles for emergency management community engagement (Australian Government 2010). Others include the importance of localised approaches and shared narratives about past experiences and the value of local community-specific knowledge over (often generic) emergency management information.

The understanding of community engagement for disaster management is growing rapidly (Australian Government 2010, Attorney-General’s Department 2011, Federal Emergency Management Agency 2012). Government agencies and universities are involved in theoretical research, case studies and evaluations. In Australia this includes reviews of community education, awareness and engagement for natural hazards (Elsworth et al. 2011) and studies on bushfire risk communication to foster awareness and preparedness (e.g. Paton et al. 2006, Paton, Burdelt & Pryor 2008, Australian Government 2010, Eriksen & Gill 2010, McLennan, Paton & Wright 2015, McLennan, Paton & Beatson 2015, Eriksen et al. 2016, McLennan et al. 2017,). Key areas of research are risk perception, homeowner preparedness and response during fires and community safety (e.g. Moritz et al. 2014, McLennan et al. 2017). Key studies in these areas in the US include Daniel, Carroll and Moseley (2007), McCaffrey and colleagues (2012) and Steelman and McCaffrey (2014). These studies identify a lack of empirical case studies on risk and crisis communication and highlight the value of communication that takes an event-based approach. Similarly in Australia, there are few published accounts of community-based bushfire safety initiatives with data about their impact. Research by Eriksen and Gill (2010) explores the ‘disconnect’ that exists between bushfire awareness and preparedness in relation to bushfire in rural landscapes in Australia. This ‘awareness-action gap’ reflects the complex and paradoxical relationship between action, awareness and attitudes (Eriksen & Gill 2010, p. 814) and reinforces the need for more studies that evaluate effects of communications that aim to educate people about risk.

The risk communication case study reported here is based in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales, where a largely transient population has never experienced a high-intensity fire event. Motivating residents to be prepared for a fire despite the lack of a sense of immediacy is challenging. This case study presents an evaluation of the effectiveness of a film that takes an event-based approach to demonstrate fire risk. Use of the film to internalise risk awareness and to motivate residents to be bushfire-prepared is examined.

Audiovisual material developed for community bushfire safety education includes two films about fires in Tasmania in 1961 and 1967 produced by the Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre and state fire and land management agencies. The use of film and oral history as a tool for learning about natural disasters is well researched. For example, exploring the role of narrative in relation to memory of floods in England (McEwen et al. 2016, Garde-Hansen et al. 2016). McEwen and colleagues take an approach to memory work that is community-focused and archival, ‘to increase understanding of how flood memories provide a platform for developing and sharing lay knowledges, creating social learning opportunities to increase communities’ adaptive capacities for resilience’ (2016, p. 14).

The Blue Mountains is part of the Great Dividing Range to the west of Sydney and one of the most fire-prone areas in the world (Chapple et al. 2011). On average, the region has 28 bushfires a year and up to seven of these can be classified as ‘major’ fires (Blue Mountains Bushfire Risk Management Plan 2013). The area’s townships have a total population of about 80,000, mostly clustered around the Great Western Highway that runs along a ridge-top. The townships are surrounded by a one million-hectare conservation area (the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area) dominated by fire-dependent eucalypt forest. The Blue Mountains Local Government Area covers 143,000 hectares. There is a narrow transition zone between the unpopulated, fire-adapted natural landscape and the populated areas. In this landscape, fire management is government-driven by the NSW Rural Fire Service, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service of the Office of Environment and Heritage and the Blue Mountains City Council. Yet the policy of shared responsibility increases the onus on communities to be better prepared to respond to bushfire threat. The effects of climate change and altered fire regimes since European settlement and the number of severe, uncontrolled bushfires in Australia has increased (Whelan et al. 2006, Kingsford & Watson 2011). A transient and increasingly urbanised population adds to the challenge, with many residents in the Blue Mountains having little or no experience of bushfire. Eriksen and Gill (2010) conclude that diverse communities with lifestyles and values more aligned with urban living present challenges for bushfire policy implementation.

The documentary film, Fire Stories - A Lesson in Time, presents a narrative of devastating fires in the upper Blue Mountains in 1957 that destroyed over 170 homes. The film’s purpose was to allow local communities to learn from a previous disaster. The 35-minute film was produced by the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute in partnership with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, NSW Rural Fire Service and the Blue Mountains City Council. The film portrays local residents describing their experience of the 1957 bushfires and reflecting on what they learnt. Historical and contemporary material was used to show the 1957 fires and the impact. This included archival and private film of the fires, personal and community stories from witnesses to the event, graphic mapping of the path of the fire and contemporary fire awareness and safety messages delivered by people from the local community and fire and emergency services personnel.

Fire Stories was part of a community engagement project designed to convert community recognition of bushfire threat into the actions of ‘Prepare, Act, Survive’ as outlined in the NSW Rural Fire Service strategy.1

In June and July 2013 (when the threat of fire is low) the film was viewed by 2600 people at two cinema events that included a bushfire information expo and presentations by fire agency personnel to generate information exchange and discussion. In addition, the local community newspaper, the Blue Mountains Gazette, ran a series of articles on the project, including 1957 eyewitness accounts, in the lead-up to and coinciding with the film screenings. To date, another 12,000 people have viewed the film on YouTube or DVD.2

In October 2013, four months after the release of Fire Stories, severe bushfires struck the Blue Mountains. Around 200 families lost their homes and a similar number of homes were damaged, approximating the property losses of 1957. This presented an opportunity to examine whether viewing Fire Stories had prompted a change in behaviour before, during and after the 2013 fire by people who had seen the film. This evaluation is important for informing community education for bushfire awareness and preparedness.

Eighteen months after the 2013 fires (allowing for a period of recovery) people who had seen the film either in the cinema or via YouTube/DVD were invited to complete an online survey using Survey Monkey. The survey sought to understand:

Respondents were recruited via direct email from the film audience database and through promotion in newspapers and via social media. The survey was conducted over four weeks in April–May 2015.

Two survey questionnaires were developed, tailored to different audiences:

Survey data were collected on a range of variables, mostly through precoded questions that allowed multiple responses. Fields for open text encouraged people to elaborate on their answers. Three different time periods were specified. For the cinema audience these were:

Two survey sections asked about bushfire preparation. The first related to bushfire preparedness activities. The second related to spheres of concern around bushfire threat, namely:

If respondents reported changes in activities or spheres of concern over time, they were asked for the reasons. To assist respondents distinguish the film’s effects from that of other bushfire awareness-raising activities (and from the experience of the 2013 fires) other known community education and engagement activities were included in the response options. Other sections of the survey asked about thinking and talking about Fire Stories and the impact (high, moderate or minimal) of the various film elements on bushfire risk perception.

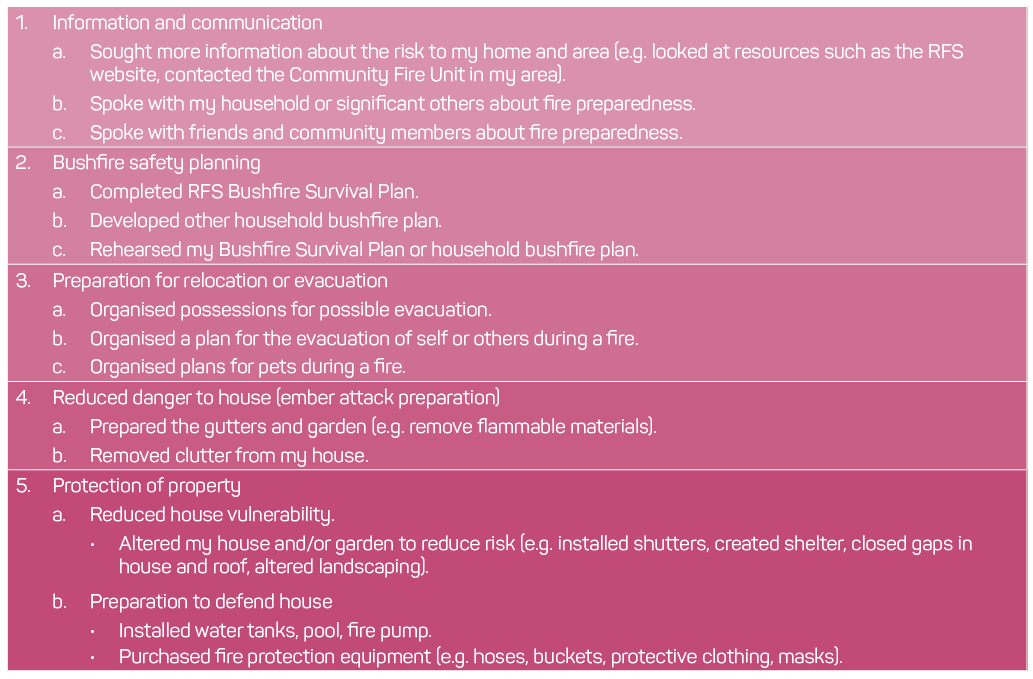

Answers to precoded questions were tabulated and converted into percentages (of the total number of responses to the question and the number of survey participants who responded to the question) for comparison across the different time periods. Answers to open-ended questions were reviewed for additional information and insights. To analyse the responses for bushfire preparedness, the classification system developed by McLennan, Elliot and Wright (2014) was used (see Figure 1). The five categories reflect a graduation in time and effort (note this does not imply a linear relationship form one to the next) from becoming risk aware, to being informed and preparing a plan, to preparing for relocation or evacuation, to reducing risk to houses and property. The last category includes more complex and often costly activities associated with altering the property to make it less vulnerable, and preparing to defend it.

A public seminar was held at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre in November 2015 to present and discuss the findings. It drew 80 attendees including survey participants, local government and community organisation representatives and the general public.

A total of 104 online questionnaires were completed: 84 from the cinema audience and 20 from the YouTube/DVD audience. Results are based on responses from the cinema audience attendees who saw the film in the context of an information and discussion-rich environment:

Due to the relatively small number in the YouTube/DVD audience sample, extensive analysis was not undertaken; however the general trends were consistent with the larger survey group.

Table 1 shows bushfire preparedness activities reported by category and time period. In the 3-4 months between watching the film and the 2013 fires, the 84 cinema audience respondents reported a total of 257 activities of which 153 were undertaken for the first time (‘new’ activities) and 104 were additional (‘more’ activities). For the period during and after the 2013 bushfires, 378 activities were reported (see last row of Table 1).

| Activity options | Time before film (Bf) (N=84) | Time after film and before bushfires (AV/BBf)(N=84) | Time during/ after bushfires (ABf) (N=83*) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New | More | Total | ||||

|

1. Information and communication |

Sought more information about risk to home/area |

45 |

19 |

7 |

26 |

33 |

|

Spoken with my household or significant others about fire preparedness |

44 |

19 |

18 |

37 |

39 |

|

|

Spoken with friends/community about fire preparedness |

40 |

16 |

17 |

33 |

38 |

|

|

Subtotal activities |

129 |

54 |

42 |

96 |

110 |

|

|

2. Bushfire safety planning |

Completed a RFS Bushfire Survival Plan |

24 |

14 |

3 |

17 |

17 |

|

Developed another household bushfire plan |

20 |

15 |

3 |

18 |

18 |

|

|

Rehearsed my Bushfire Survival Plan or household bushfire plan |

14 |

6 |

1 |

7 |

16 |

|

|

Subtotal activities |

58 |

35 |

7 |

42 |

51 |

|

|

3. Preparation, relocation, evacuation |

Organised possessions for possible evacuation |

39 |

18 |

11 |

29 |

41 |

|

Organised plan for evacuation of self or others |

34 |

10 |

9 |

19 |

36 |

|

|

Organised plans for pets during fire |

30 |

7 |

8 |

15 |

24 |

|

|

Subtotal activities |

103 |

35 |

28 |

63 |

101 |

|

|

4. Reduced danger to house |

Prepared the gutters and garden |

57 |

11 |

17 |

28 |

52 |

|

Removed clutter from my house |

34 |

9 |

6 |

15 |

31 |

|

|

Subtotal activities |

84 |

20 |

23 |

43 |

83 |

|

|

5a.Protection of property - reduced house vulnerability |

Altered house and garden to reduce risk |

25 |

5 |

3 |

8 |

17 |

|

Subtotal activities |

25 |

5 |

3 |

8 |

17 |

|

|

5b.Protection of property - preparation to defend house |

Installed water tanks, pool, fire pump |

23 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

|

Purchased fire protection equipment |

28 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

11 |

|

|

Subtotal Activities |

43 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

16 |

|

|

Grand total activities |

457 |

153 |

104 |

257 |

378 |

|

For the two most easily achieved categories, reported activity after viewing Fire Stories approached that associated with the 2013 bushfires. Reported information and communication activity after the film and before the fire was 87 per cent of that during of after the fire. Further, 56 per cent of that activity was new. Reported bushfire safety planning and rehearsal after viewing/before the fire, was 82 per cent of that after the fire, with 82 per cent being new. Relative to the before-film baseline of 58 activities, this category showed the largest proportional increase in activity. Indeed, completion of a Rural Fire Service Bushfire Survival Plan after the film and before the fire was on par with that during or after the fire.

A total of 103 activities around preparation for relocation/evacuation occurred before the film. In the period after the film and before the fire, 63 actions (35 ‘new’ and 28 ‘more’) were undertaken: 29 for possessions, 19 for persons (self or others) and 15 for pets. This was 62 per cent of the activity reported during or after the fire. Reported activity to reduce danger to the house in the after viewing/before fire period was 52 per cent of that after the fire. Roughly half as many respondents prepared the gutters and garden before the fire as did after (33 per cent and 63 per cent, respectively). With respect to protection of property, few respondents reported installing or purchasing fire protection equipment in the 3-4 months after viewing Fire Stories; more reported these activities after the fire.

Respondents gave 111 reasons for additional bushfire safety activity between viewing the film and the 2013 fire event, of which 79 (72 per cent) were related to Fire Stories, including the film, newspaper articles and the information expo. The following quotations are illustrative:

Once the 2013 bushfire began, from a total of 152 reasons for additional bushfire safety activity, 43 per cent related to Fire Stories and 39 per cent to the experience of the fires.

There was a noticeable broadening of spheres of concerns after the film and before the fire (see Figure 2). Before viewing the film, the overwhelming focus of concern was ‘home and household’ (reported by 86 per cent of respondents), followed by ‘pets’ (52 per cent) and ‘immediate neighbour’ (49 per cent). Approximately one-third of respondents nominated ‘street’, ‘neighbourhood’ and ‘someone nearby who needs help’. In the period after seeing the film and before or during the fire (AV/BBf in Table 3), 20 respondents indicated a new concern for their street (80 per cent increase on before the film), 19 did so for their neighbourhood (70 per cent increase) and 16 did so for ‘someone nearby who needs help’ (57 per cent increase). During or after the fire, these new concerns seem to have been sustained.

Respondents commonly credited viewing the Fire Stories film for changes in both time periods (before or during/after the fire). Of the 101 reasons for changes to spheres of concern before the fire, 78 per cent were elements of the Fire Stories project: 46 (57 per cent) respondents cited the film, 19 (23 per cent) cited newspaper coverage and 14 (17 per cent) the information expo. Of the 114 reasons for changes to spheres of concern once the fires commenced, 61 (53 per cent) related to Fire Stories with 37 (46 per cent) respondents citing the film, 17 (21 per cent) citing newspaper coverage and 7 (9 per cent) the information expo. This exceeded the influence of the experience of the bushfires, which accounted for 36 per cent of the reasons given.

Sixty per cent of respondents reported thinking about the film ‘for a long time afterward’ and the same percentage ‘leading up to and during the following bushfire season’. Another 40 per cent thought about the film ‘especially during the 2013 bushfire threat’. The film prompted discussion, particularly about bushfire behaviour and preparation. People most often talked about the ‘potential severity of Blue Mountains bushfire’ (61 of 73 respondents or 83 per cent) followed by ‘people and history in the film’ (79 per cent) and ‘how to prepare for bushfire’ (67 per cent). Discussion most often occurred with families and friends (90 per cent) followed by community members (59 per cent), neighbours (45 per cent) and work colleagues (42 per cent). Respondents reported taking the conversation into groups and schools and some discussed the film with visitors to the mountains.

Of 76 respondents who replied to the question, 85 per cent rated the film as either very effective or effective (50 and 35 per cent, respectively) in promoting community preparedness and resilience. As shown in Figure 2, the element with the most frequent ‘high impact ‘ rating (71 per cent) was the graphic map of the movement of the fire. This element was instrumental in depicting the speed and extent of the fire complementing the archival footage and people talking. There were also rated by a majority of respondents as having a ‘high impact’.

The evaluation of the Fire Stories project highlights the value of risk education that takes an event-based approach. The film provided viewers with the vicarious experience of a major fire event, using visual technology to convey the speed, unpredictability and destructiveness of fire in familiar locations to personalise the experience. It assisted respondents to come to terms with, and to overcome impediments to, being prepared for fire events and helped stimulate readiness and mitigation actions. Fire Stories prompted a substantial increase in bushfire safety activity in the lead-up to the 2013 bushfires. The effect was sustained over the 20 months to the date of the survey. The film also produced a shift in focus of concern when preparing for bushfire to include greater concern for community including others in their street, neighbourhood and vulnerable people.

The behaviour of the catastrophic 1957 fire-affected respondents powerfully. The motivational effect of the film on fire preparedness and response was comparable to that of an actual fire of similar magnitude. Indeed, it was comparable to the experience of the 2013 bushfires for three of the five behaviour change categories: information and communication, bushfire safety planning and planning for relocation or evacuation. It was also followed by considerable new and additional activity related to protection of property.

These findings concur with a US study of homeowners in a wildland–urban interface, which found that higher subjective bushfire knowledge increased risk perception, in turn leading to more risk reduction actions (Martin et al. 2009). From a literature review that triangulated bushfire, risk and crisis, Steelman and McCaffrey (2014) identify the characteristics of effective communication. Fire Stories represents each of these, being interactive processes that allow for dialogue and risk clarification, taking local context into account, ‘reliable and honest’ sources and ‘credibility of the messenger’ (p. 688). Of nine best-risk communication practices identified by Sellnow and colleagues (2009), several relate to Fire Stories: involving the public in a dialogue about risk, presenting risk messages with honesty, remaining open and accessible to the public, designing messages to be culturally sensitive and collaborating and coordinating credible information sources. Elements of the film project that contributed to its impact were agency collaboration, quality documentary film techniques, local and personal stories and settings and confronting content in a supportive community setting.

A key feature of Fire Stories may be that it is not a generic emergency management message. It sidesteps the ‘official rationality of bushfire management’ (Eriksen & Gill 2010, p. 815) and the ‘strategy’ of institutions and structures of power (de Certeau 1984, p. 110). Elements of the film that evoked the ‘now I get it’ response include, the archival footage of the 1957 fires burning familiar and inhabited locations and augmented by spatial mapping of the path of the fire to depict the speed and ferocity of the event. This visual depiction of the spatial mapping and movement of the fire appeared to be effective in informing people about fire behaviour and may have helped to overcome the ‘limited understanding of fire behaviour, …despite the high level of risk recognition’ as observed by Beilin and Reid (2014, p. 42) in rural and peri-urban landscapes in Australia. ‘People’s responses are complex and constructed based upon an analysis of local conditions, prior experience and newly organised or reorganised social memory’ (Beilin & Reid 2014, p. 42). An ‘intuitive understanding’ of risk in their landscape and home places can physically be made ‘real’ by seeing this map, ‘bringing together the rational and the intuitive’ (Beilin & Reid 2014, p. 47).

A second effective element of the film was personalising the experience using local eyewitness accounts. Showing how people who have lived through devastating fire and who have witnessed the scale of destruction can recover and using these people to talk about protecting property and living safely in a bushfire-prone area was powerful.

The film was part of a larger collaboration and community engagement campaign. Thus, the film (or ‘the Fire Stories project’) incorporates the social fabric of people’s lives as highlighted in studies (e.g. de Certeau 1984, Eriksen & Gill 2010) as being important for the development of attitudes and actions relating to unpredictable and unruly ecological events, such as bushfires. Respondents acknowledged the effectiveness of the local newspaper coverage of the film project and the bushfire information expo.

Fire Stories addresses the challenges outlined by Eriksen and Gill (2010) for community outreach programs that meet the need for ‘local, socially contextualised and interactive initiatives’ that appeal to a diverse community (p. 824). This study reinforced the benefits of alternative community-based approaches that enhance the effectiveness of community bushfire safety endeavours. Films that present personal narratives of past experiences can allow social learning based on storytelling. The Fire Stories film project can be described variously as a means of communication, an education activity and a mode of engagement. Knowledge is the end product and the film provides experiential learning that can be as effective as direct experience of a fire. This evaluation demonstrates the value and function of bushfire memory ‘as a tangible and travelling discourse’ (Garde-Hansen et al. 2016, p. 1). The film project helped to build understanding of bushfire and the implications of living in fire-prone areas.

This evaluation was supported by a Blue Mountains Flexible Community Grant from the NSW Department of Premier and Cabinet. Glenn Meade of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service is acknowledged for the original idea to make the Fire Stories film, and recognition for the making of the film is due to John Merson and Peter Shadie of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute and to Laura Zusters (film director). We thank all those who took time to complete the survey.

Australian Government 2010, Manual 45. Guidelines for the Development of Community Education, Awareness and Engagement Programs. Canberra: Australian Emergency Manuals Series.

Beilin R & Reid K 2014, Putting ‘it’ together: Mapping the narratives of bushfire and place in two Australian landscapes. Final report for the social construction of fuels in the interface (Project two). Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre, Victoria. At: www.bushfirecrc.com/sites/default/files/managed/resource/putting_it_together_final_report.pdf.

Attorney-General’s Department 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience Community Engagement Framework. Canberra, ACT. At: www.coag.gov.au/node/81.

Chapple RS, Ramp DR, Kingsford RT, Merson JA, Bradstock RA, Mulley RC & Auld T 2011, Integrating science into management of ecosystems in the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, Australia. Environmental Management, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 659-674.

de Certeau M 1984, Arts de Faire: The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Daniel TC, Carroll MS & Moseley C 2007, People, fire and forests: a synthesis of bushfire social science. OSU Press, Corvalis.

Ellis S, Kanowski P & Whelan RJ 2004, National Inquiry on Bushfire Mitigation and Management. Council of Australian Governments, Canberra.

Elsworth G, Gilbert J, Robinson P, Rowe C & Stevens K 2009, National review of community education, awareness and engagement for natural hazards: final report. School of Global Studies, Social Science and Planning, RMIT University. At: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.3/219983.

Eriksen C & Gill N 2010, Bushfire and everyday life: examining the ‘awareness-action gap’ in changing rural landscapes. Geoforum, vol. 41, pp. 814-825.

Eriksen C, Penman T, Horsey B & Bradstock R 2016, Wildfire survival plans in theory and practice. International Journal of Wildland Fire, vol. 25, pp. 363-377.

Federal Emergency Management Agency 2012, Crisis Response and Disaster Resilience 2030: Forging Strategic Action in an Age of Uncertainty. Progress Report Highlighting the 2010-2011 Insights of the Strategic Foresight Initiative, Washington, US Department of Homeland Security.

Garde-Hansen J, McEwen L, Holmes A & Jones O 2016, Sustainable flood memory: Remembering as resilience. Memory Studies, pp. 1-22. doi: 10.1177/1750698016667453

Kingsford RT & Watson JEM 2011, Climate Change in Oceania – A synthesis of biodiversity impacts and adaptations. Pacific Conservation Biology, vol. 17, pp. 270-284.

Martin WE, Martin IM & Kent B 2009, The role of risk perceptions in the risk mitigation process: the case of bushfire in high risk communities. Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 91, pp. 489–498.

McCaffrey S, Toman E, Stidham M & Shindler B 2012, Social science related to bushfire management: an overview of recent findings and future research needs. International Journal of Wildland Fire, vol. 22, no. 1. doi.org/10.1071/WF11115

McEwen L, Garde-Hansen J, Holmes A, Jones O & Krause F 2016, Sustainable flood memories, lay knowledges and the development of community resilience to future flood risk. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 14-28.

McLennan J, Elliot G & Wright L 2014, Bushfire survival preparations by householders in at-risk areas of south-eastern Australia. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 11-17.

McLennan J, Paton D & Wright L 2015, At-risk householders’ responses to potential and actual bushfire threat: An analysis of findings from seven Australian post-bushfire interview studies 20092014. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 12, pp. 319-327.

McLennan J, Paton D & Beatson R 2015, Psychological differences between south-eastern Australian householders’ who intend to leave if threatened by a wildlfire and those who intend to stay and defend. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 11, pp. 35-46.

McLennan J, Every D, Bearman C & Wright L 2017, On the concept of denial of natural hazard risk and its use in relation to householder wildfire safety in Australia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 21, pp. 176-186.

Moritz MA, Batllori E, Bradstock RA, Gill AM, Handmer J, Hessburg PF, Leonard J, McCaffrey S, Odion DC, Schoennagel T & Syphard AD 2014, Learning to co-exist with fire. Nature, vol. 515. doi:10.1038/nature13946

NSW Rural Fire Service 2013, Blue Mountains Bushfire Risk Management Plan 2013. At: www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/24369/Blue-Mountains-Bush-Fire-Management-Plan_Reviewed-2013_-FINAL-DRAFT-FOR-REVIEW.pdf#Draft Bush Fire Risk Management Plan [30 August 2016].

Paton D, Kelly G, Burgelt P & Doherty M 2006, Preparing for bushfires: understanding intentions, Disaster Prevention Management, vol. 15, pp. 566–575.

Paton D, Burgelt P & Prior T 2008, Living with bushfire risk: social and environmental influences on preparedness, Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 41–48.

Sellnow TL, Ulmer RR, Seeger MW & Littlefield R 2009, Effective risk communication: a message centered approach. Springer Science and Business Media, New York.

Steelman TA & McCaffrey S 2013, Best practices in risk and crisis communication: Implications for natural hazards management. Journal of the International Society for the Prevention and Mitigation of Natural Hazards, vol. 65, pp. 683-705.

Toman E, Shindler B & Brunson M 2006, Fire and fuel management communication strategies: citizen evaluations of agency outreach activities. Society for Natural Resources, vol. 19, pp. 321–336.

Whelan R, Kanowski K, Gill M & Andersen A 2006, Living in a land of fire, article prepared for the 2006 Australia State of the Environment Committee, Department of Environment and Heritage, Canberra. At: www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/ff5cd9e1-1929-4617-8bad-89492b4e70ad/files/fire.pdf [23 February 2017].

Dr Rosalie Chapple is a Sessional Lecturer at the University of New South Wales. She is a co-founder and Director of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute.

Dr Ilse Blignault is a Principal Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Research at Western Sydney University and Senior Visiting Fellow at the School of Public Health and Community Medicine at the University of New South Wales

Anne Fitzgerald is a Blue Mountains-based social worker and consulting social researcher and project coordinator, specialising in cultural and community engagement and media and communications.

1 NSW Rural Fire Service Plan and Prepare. At: www.rfs.nsw.gov.au/plan-and-prepare

2 Based on sales.