A central premise of this framework is that while Australia’s disaster resilience policy choices may be sound, policy goals cannot be achieved without effective implementation. A review of disaster resilience policy implementation is needed to evaluate what has been done so far and to inform future approaches. This would determine whether implementation is consistent with achieving disaster resilience outcomes and goals, and the extent to which resilience is driving developments in the emergency management system. This research contributes to the academic literature on disaster resilience and policy implementation and provides information about operationalising resilience policy that can be applied in policy and program developments.

In early 2011, all levels of Australian governments adopted the NSDR (Commonwealth of Australia 2011), which emphasises prevention, preparedness and mitigation over the historical focus on relief and recovery. The NSDR consists of broadly-based principles designed to be followed by state and territory governments with subsequent flow-on to local government and other sections of the community.

The NSDR is largely instrumental and, not uncommonly, was implemented in a policy environment of incomplete evidence. One of the reasons for this is that the rise of resilience in public policy, including in disaster management policy, had overtaken available research, particularly in the field of policy implementation. This remains the case. Four years, and several changes of government later, the resilience paradigm is showing no signs of waning and with the Australian Government currently reviewing the NSDR (Law Crime and Community Safety Council 2014a) it is important to turn attention to disaster resilience policy development and its implementation. If emergency management policy in Australia intends to retain resilience as its fundamental guiding principle, there needs to be more certainty about how resilience can be enabled at all levels.

Mainstream commentary tends to emphasise the limitations of resilience research and the effect this has on policy efficacy, particularly the capacity of policymakers to analyse and evaluate resilience policies and programs. This is not entirely accurate. The evidence base has grown substantially over the past decade, primarily in the areas of definition, concepts, models and the development of instruments for measuring resilience. However, gaps are most evident in resilience policy implementation studies (Cork 2010), with the possible exception of ecological resilience policy implementation (Walker & Salt 2012, Alliance 2010, Salt & Walker 2006). Building resilience requires long-term commitment to action underpinned by attitudinal and behavioural change at all levels of government and in the community. Better and more detailed information and guidance is needed, not only on how to develop disaster resilience policy, but also on how to construct and design the apparatus of disaster resilience policy implementation (i.e. the laws and regulations, sub-policies, programs, institutions and governance). At the very least there needs to be greater knowledge and awareness about how to avoid undermining resilience, including as an unintended consequence of poorly designed and ill-conceived implementation practice.

Information from the Australian Government Review of Federalism, indicates a political preference for smaller government and the rolling back of the centralism that has defined government roles and responsibilities over several decades (Australian Government 2005). Putting debate on reform of the Australian federation aside, the expansion in power and influence of the Federal Government may be inconsistent with subsidiarity1, a fundamental principle of cooperative federalism (Fenna & Hollander 2013). Subsidiarity goes hand-in-hand with principles in the NSDR of sharing responsibility across all levels of government and the community. Learning more about how resilience policy implementation occurs within and between the tiers of government and the community, including the downstream and upstream impacts of federalism, will help understand how implementation is influencing policies aimed at strengthening Australia’s resilience to disaster events.

Several bodies of evidence have been identified to determine the structure of a disaster resilience implementation framework. These are:

The resilience evidence base has developed roughly in this order: definitions and conceptual models, resilience indicators and measurement tools, and methodology. The earliest mention of resilience in the context of emergencies and disasters appears in 1854 when it was used to describe the recovery of a Japanese city after an earthquake (Alexander 2006). This, by all accounts, was an anomaly as the use of resilience in relation to disasters did not appear again until early in the 21st Century. Up until then the focus was on the general concept of resilience and the development of various discipline-specific definitions. The uptake into the social sciences through anthropology in the 1950s and its emergence in the 1970s and 1980s in ecological systems literature (Holling 1973), and human and developmental psychology (Rutter & Garmezy 1983) were significant developments. The latter, particularly in terms of the general humanising of resilience and its application to individuals and the idea that resilience can deliver positive changes arising from adaptation, over and above the restoration of function to a pre-disturbance state. Major advances in social resilience research were made by Adger who linked natural ecology with human ecology (2000). Later, Norris and her colleagues (2008) expanded the concept of individual resilience to collective resilience i.e. community resilience and contextualised it to disasters

The popularity of resilience has often been viewed as an impediment to its scientific rigour. McAslan (2010) responded to this by concluding that even though definitions and descriptions of resilience were numerous and varied, they demonstrated sufficient commonality and shared characteristics to allow it to be recognised as a useful concept. Around the same time, the uptake of resilience into public policy has been a significant development. For example, the United Nations International Strategy for Risk Reduction focuses on integrating approaches for disaster risk reduction and developmental goals to achieve resilience via the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 and its predecessor, the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building Resilience of National and Communities to Disasters. In all likelihood this will stimulate further research, particularly in areas relating to measurement tools.

The work of Norris and co-authors (2008) provides the theoretical model of choice for this research because it links individual resilience to collective and community resilience. Resilience is described by Norris as ‘a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disturbance’ (Norris et al. 2008). This definition is disaster-appropriate because it explicitly refers to a shock or disturbance that is connected to, or triggers a dynamic process leading to an improvement in functioning.

Four adaptive capacities of economic development, social capital, community competence and information and communication each have inherent qualities or attributes being robustness (strength), redundancy (substitutable), and rapidity (timeliness). The validity of this theory was strengthened by the Index of Perceived Community Resilience (IPCR) (Kulig et al. 2013) that expanded Norris’s model. The IPCR was tested in two fire-affected communities in Canada using interviews, community profiles and a household survey. The IPCR proposed additional characteristics of leadership and empowerment, community engagement, and non-adverse geography that align with Norris’s social capital and community competence capacities (Kulig et al. 2013).

To understand the challenges of policy implementation research it is helpful to know that it slid into academic obscurity following a flush of interest and activity between 1980–90 (Hupe 2014). However, it did not disappear but became subsumed within other fields so that many studies can more recently be found in discipline-specific and professional journals rather than solely in the mainstream public policy and administration research literature. Some of the most relevant can be found in the ecological resilience literature, although these tend to be limited to a geographical location.

Some of the discussion on policy implementation issues dating back several decades remains relevant for disaster resilience today, including the debate about top-down verses bottom-up approaches and the emergence of the view that a combination of these two approaches is a legitimate option (Sabatier 1986), particularly for implementing disaster resilience policy (Buckle, March & Smale 2001).

The study of policy implementation is also difficult due to its complexity, not the least of which relates to the problem of ‘too many variables’ (Goggin 1986). This, combined with the diffuse nature of the evidence in the academic literature and the additional layer imposed by the implementation of resilience in a multi-level governance system, presents methodological challenges for this work.

Effective implementation arrangements need to be legal and require capabilities at two levels. They must be functional (can get the job done) and ideologically sound (principles governing activities must be consistent with the goal of building the four networked adaptive capacities for disaster resilience).

Policy implementation can be multi-layered depending on the policy objectives, stakeholders and target audiences. Many policies will be issues and interest-based, initiated by and within varying sectors, and will be worked through the system in a combination of horizontal and vertical pathways. Disaster resilience policy is no exception, and if all levels of government and the community are to assume their share of responsibility for resilience, more detailed guidance on how to implement disaster resilience policy is needed that can be used by stakeholders. Therefore, multiple layers have been built into the disaster resilience policy implementation framework.

Evidence about implementing policy that enables the four adaptive capacities and their complementary sub-scales (community engagement, leadership and empowerment, and non-adverse geography) informs normative outcomes at the broadest level of the disaster resilience policy implementation framework. It should be noted that these elements overlap as do their associated policy implementation mechanisms and actions. This does not limit the usefulness of the implementation framework but rather, provides a comprehensive menu and awareness of the mutual dependencies of the system.

Social capital is enabled by implementing policies that build informal relationships, networks and stakeholder trust, by providing information to people relevant to their own roles and values, and by giving people the skills to deal with conflict (Productivity Commission 2003). Ecological resilience is also linked to social capital and is reflected in the non-adverse geography sub-scale (Kulig et al. 2013). This highlights the importance of the physical environment in community wellbeing and provides evidence supporting the inclusion of environmental and natural resource management policy implementation within this resilience implementation framework.

A role for government in fostering community competence lies in engaging with communities to ensure that people can participate in policy development and implementation, including by facilitating local level leadership.

Normative policy outcomes of equity and diversity of economic assets (Norris et al. 2008) within communities can be influenced via government policies on taxation, social welfare and other redistributive strategies, employment, small business, regional development, foreign investment, competition, superannuation, and energy to name a few.

In relation to information and communication, communities tend to look to government for reliable and accurate information about issues of public importance. Government needs to formulate and lead effective communications activities during and in the aftermath of disasters (Conkey H 2004). Government is well-placed to marshal the professional skills and substantial financial resources needed for conducting national public awareness and information campaigns. Evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach can be found in national strategies relating to public health and road safety (Delaney et al. 2004). Conversely, a role for government in ensuring a responsible media (another key element of information and communication adaptive capacity) is less clear.

The context for policy implementation is critical for shaping its outcomes (Coffey 2014). Analysis of the policy context informs decisions about allocation of responsibility, the role of levels of government, and the mechanisms available to government for implementing policy.

The notion of multi-level governance, the overarching theoretical model for the Australian government system, provides the context for the proposed framework. This translates into national, sub-national and local implementation platforms. The Australian Constitution2, at the highest level, provides the legal framework for the system.

Discussion about federalism in Australia is well-developed in the public administration and public policy literature and is central to the consideration of the role of government in the development of the disaster resilience policy implementation framework. The federalism literature provides the following reference points for developing a disaster resilience framework:

However, pathways to achieving outcomes that lie outside of government become increasingly less evident as the goal of implementation moves away from government and onto communities and householders. Therefore it becomes critical to identify implementation mechanisms that are obscure or non-existent and support community engagement, participation and partnerships for resilience.

The structure of the framework takes account of implementation plus the level at which implementation should occur within the federal system and its sub-systems. For example, does a policy need to be whole-of-government i.e. initiated and overseen at the federal level through a body such as the Council of Australian Governments and have corresponding implementation machinery within each state and territory government, then also be reconstituted at the local government level down to individuals? The answer is, ‘it depends’. It depends on the nature of the policy: what it is seeking to achieve or change and the capability to achieve that change at each level of the system. These issues are fundamental to subsidiarity and the debate about centralism verses devolution. Therefore, in terms of a principle for successful policy implementation, subsidiarity is key and ‘a potentially powerful concept around which a debate about the optimal assignment of tasks across different administrative levels could be constructed’ (Jordan 1999).

Policy implementation can also be described as a system that gives rise to policy implementation mechanisms including sub-policies, laws, programs, institutions and governance arrangements. These offer relatively tangible units for analysis and provides structure that helps manage complexity. The implementation mechanisms operate at each level within Australia’s federal system, i.e. at national, sub-national (state and territory government), and local government levels. These have been incorporated into the framework because they help identify an appropriate role for government and can point to the types of resilience-building activities that are appropriate.

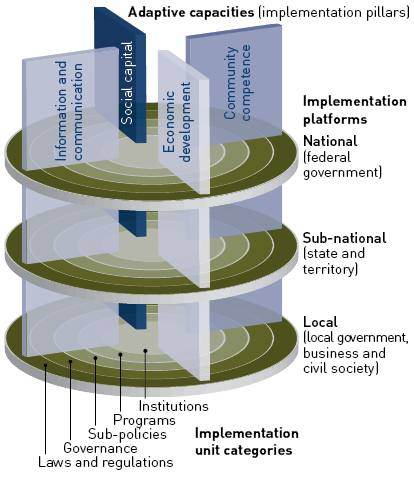

Figure 1 provides a structural concept for the disaster resilience implementation framework. The four networked adaptive capacities of economic development, community competence, social capital and information and communication form the implementation pillars. These intersect with the three implementation platforms of the national (Australian Government), sub-national (state and territory), and local (local government, business and civil society). Each of the platforms contain implementation units consisting of sub-policies, laws and regulations, governance, institutions and programs. Implementation mechanisms operate within the implementation units. For example, federal policy implementation arrangements include political mechanisms, federal financial arrangements such as intergovernmental agreements, federal legal frameworks (such as The Australian Constitution), whole-of-government and national policy implementation arrangements, both formal and informal, and intergovernmental institutions e.g. Council of Australian Governments.

Qualitative research methods were used to test and develop the disaster resilience implementation framework, which also serves as the analytical framework for the research. The first step was to identify the theoretical characteristics of resilience. The model of ‘networked adaptive capacities’ was chosen. Next, evidence for enabling the disaster resilience adaptive capacities of economic development, social capital, community competence and information and communication was explored. These are broad concepts that lack specificity and present methodological difficulties in terms of isolating elements for a policy implementation framework. With a shortage of resilience policy implementation information and absence of reviews and evaluation findings on the NSDR, evidence from evaluation and reviews of other Australian national strategies provided a valuable source of information.

In addition to Norris and co-authors (2008) and Kulig and colleagues (2013), the terms of the analysis were adapted from the following sources: The Productivity Commission (2003) and Australian Bureau of Statistics (2004) on social capital, Handmer and Dovers (2013) on information and communication as a ‘universal’ policy instrument and the role of community participation, Richardson (2014) in relation to security as an outcome for economic development, Hussey and co-authors (2013) regarding intra governmental and administrative policy mechanisms, links between stakeholder engagement and leadership and empowerment (Porteous 2013), and Fenna and Hollander (2013), Jordan (2013) and Mcallister, Dowrick & Hassan (2003) on principles of cooperative federalism. In developing the methodology, guidance was obtained from Statutory frameworks, institutions and policy processes for climate adaptation: Final Report (Hussey et al. 2013). Table 1 lists the desired policy implementation actions and outcomes for each of the four adaptive capacities.

ANU human research ethics approval has been obtained for the empirical component of this research. This consists of four case studies corresponding to each of the four adaptive capacities. Data is being collected from a sample of programs or initiatives with explicit disaster resilience and natural hazard risk reduction or mitigation objectives. These have been chosen from each of the three levels of government, from business and the not-for-profit sector.

Data collection involves initial document study, followed by structured interviews. Questions have been designed to draw out detailed information about the way each of the resilience initiatives are being implemented in relation to the actions or outcomes in Table 1. The interview responses will be analysed in terms of the actions or outcomes in Table 1 as well as the policy implementation information obtained from the document study. Particular regard will be given to whether or not, and how, approaches to implementation are a function of federalism. Consistent with the key principle of subsidiarity, the notion of centralism verses devolution and the direction of implementation (vertical, horizontal or multi-directional) will also be considered in the analysis.

Table 1: Disaster resilience policy implementation – networked adaptive capacities.

| Adaptive capacity | Social capital | Community competence | Economic development | Information and communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Actions and outcomes |

Networks Non-adverse geography or place-based Community engagement Leadership (internally focused) |

Political partnerships Stakeholder engagement Leadership (externally focused) and empowerment Community participation |

Security Economic diversity Equity of resource distribution Sustainability Shared (equitable) risk allocation |

Narratives Responsible media and access to trusted information Skills and infrastructure Information flow between sectors |

While it appears as if much has been achieved by the NSDR in terms of embedding disaster resilience policy at the highest level, research about how policy implementation enables resilience needs to be incorporated into approaches for building resilience. Similar to areas of social policy research, this poses considerable challenges in terms of managing and synthesising information about implementation issues that contribute to policy outcomes. However, these are challenges that must be tackled as Australian political leaders and policy makers review the NSDR and the federal arrangements that give it effect. This paper outlines a concept, broad architecture and methodology for a framework to guide effective ways of implementing disaster resilience policy. The disaster resilience policy implementation framework provides clarity for achieving the four resilience adaptive capacities of community competence, social capital, economic development and information and communication. Early findings suggest useful lessons are available from evaluations of various strategic policies. Next, case studies involving each level of government, the business and not-for-profit sectors will assist in refining the framework, as well as delivering specific information about implementation of the NSDR.

This work being conducted at the Australian National University is also funded, in part, by the Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre.

Adger WN 2000, Social and ecological resilience: are they related? Progress in human geography, 24, pp. 347-364.

Alexander D 2006, Globalisation of disaster: trends, problems and dilemmas. Journal of International Affairs, 59, no. 2, p. 1. At: www.policyinnovations.org/ideas/policy_library/data/01330/_res/id=sa_File1/alexander_globofdisaster.pdf.

Alliance R 2010, Assessing resilience in social-ecological systems: Workbook for practitioners. Version, 2, p. 53.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2004, Measuring social capital: an Australian framework and indicators. Information paper. Canberra.

Australian Government 2005, Terms of Reference: Reform of the Federation White Paper [Online]. Canberra. At: https://federation.dpmc.gov.au/ [23 February 2015].

Buckle P, Marsh G & Smale S 2001, Assessment of personal and community resilience and vulnerability. Emergency Management Australia.

Coffey B 2014, Overlapping forms of knowledge in environmental governance: Comparing Environmental Policy Workers’ Perceptions. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice.

Commonwealth of Australia 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Building the resilience of our nation to disasters. Council of Australian Governments.

Commonwealth of Australia 2012, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience: Companion Booklet.

Conkey H 2004, National crisis communication arrangements for agricultural emergencies. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 43-46.

Cork S 2010, Resilience and transformation: preparing Australia for uncertain futures. CSIRO Publishing.

Delaney A, Lough B, Whelan M & Cameron M 2004, A review of mass media campaigns in road safety. Monash University Accident Research Centre.

Fenna A & Hollander R 2013, Dilemmas of Federalism and the Dynamics of the Australian Case Australian Journal of Public Administration, 72, pp. 220-227.

Galligan B 2002, Australian Federalism: A Prospective Assessment. Publius, 32, pp. 147-166.

Goggin ML 1986, The ‘Too Few Cases/Too Many Variables’ Problem in Implementation Research. The Western Political Quarterly, 39, pp. 328-347.

Handmer J & Dovers S 2013, Handbook of Disaster Policies and Institutions: Improving Emergency Management and Climate Change Adaptation, Routledge.

Holling CS 1973, Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecological Systems, 4, pp. 1-23.

Hupe P 2014, What happens on the ground: Persistent issues in implementation research. Public Policy and Administration, 29, pp. 164-182.

Hussey K, Price R, Pittock J, Livingstone J, Dovers S. Fisher D & Hatfield-Dodds S 2013, Statutory frameworks, institutions and policy processes for climate adaptation. Gold Coast: National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility.

Jordan A 1999, The multi-level politics of European environmental governance: a review article. Public Administration [HW Wilson - SSA], 77, 662.

Kulig JC, Edge DS, Townshend I, Lightfoot N & Reimer W 2013, Community Resiliency: Emerging theoretical insights. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, pp. 758-775.

Law Crime and Community Safety Council 2014a, Communique. Canberra. Communique [Online]. At: www.lccsc.gov.au/agdbasev7wr/sclj/lccsc%20meeting%204%20july%202014%20-%20communique.pdf.

Mcallister I, Dowrick S & Hassan R 2003, The Cambridge handbook of the social sciences in Australia, New York, Cambridge University Press.

McAslan A 2010, The concept of resilience: understanding its origins, meaning and utility. Torrens Resilience Institute, Adelaide.

Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF & Pfefferbaum RL 2008, Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, pp. 127-50.

Porteous P 2013, Localism: from adaptive to social leadership. Policy Studies, 34, pp. 523-540.

Productivity Commission 2003, Social Capital: Reviewing the Concept and its Policy Implication. Research Paper, Ausinfo. Canberra.

Rutter M & Garmezy N 1983, Developmental Psychopathology. In: Hetherington, E. M. (ed.) Mussen’s handbook of child psychology: Socialisation, personality and social development. New York: Wiley.

Sabatier PA 1986, Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches to Implementation Research: a Critical Analysis and Suggested Synthesis. Journal of Public Policy, 6, pp. 21-48.

Salt D & Walker B 2006, Resilience thinking: sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world, Washington, Island Press.

Walker B & Salt D 2012, Resilience practice: building capacity to absorb disturbance and maintain function, Island Press.

Susan Hunt worked in the Australian Public Service for 18 years prior to commencing PhD studies in 2014. During that time she developed national mental health and national disaster management policies and programs. This followed her earlier career as a general and mental health nurse where she worked in clinical settings and in community health and health education in the Hunter region of NSW.

1 The principle that says action should be taken at the lowest effective level of governance. Jordan A 1999, The multi-level politics of European environmental governance: a review article. Public Administration [HW Wilson - SSA], 77, pp. 662.

2 The Australian Constitution. At: www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/Constitution.