Reviewed by Joshua Whittaker, RMIT University

Published by Liverpool University Press in 2014, ISBN 978-1-78138-123-6

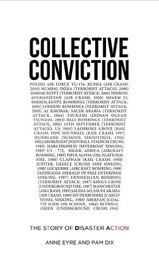

How do survivors and bereaved people experience disasters and the aftermath? How do they cope with their experiences, seek justice for victims, and hold those responsible accountable? These are some of the questions explored by Anne Eyre and Pam Dix in Collective Conviction: The Story of Disaster Action.

This book tells the story of a UK charity founded in 1991 by survivors and bereaved people of disasters affecting UK citizens in the late 1980s. The organisation, Disaster Action1, has three main aims: to hold those responsible for disasters accountable, to provide support to survivors and bereaved people, and to prevent future disasters by learning from past events, campaigning for law reform, and increasing public access to safety information. Both authors are founding members of the London-based organisation. Eyre, a sociologist at the University of Leicester, survived the 1989 Hillsborough Stadium disaster in Sheffield, England. Dix, a publishing editor, writer and researcher, lost her brother in the 1988 Pan Am 103 bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland.

The book sets out the history of Disaster Action, from its origins in a number of disaster support groups, to its present-day status as an established but independent disaster organisation with strong institutional ties. Early chapters document the ‘decade of disaster’ that was the 1980s and the ‘common bond’ that brought survivors and bereaved people together for support and to campaign for corporate responsibility and law reform. This period saw an alarming number of transport and industrial disasters such as the 1987 capsizing of the Herald of Free Enterprise in Zeebrugge Harbour, Belgium (193 killed), the 1988 Piper Alpha oil platform explosion in the North Sea (167 killed), and the 1988 Clapham Junction rail crash in London (36 killed, 120+ injured). Middle chapters discuss the principles that guide Disaster Action’s activities (‘Accountability, Support, Prevention’), its engagement with disaster management organisations, and the needs and rights of those in disaster. Later chapters focus on corporate responsibility and the law, engaging the media, and Disaster Action’s achievements and legacy. A significant part of the book (pp. 181-274) consists of appendices, the majority of which is a reproduction of Disaster Action’s ‘When disaster strikes’ and ‘Guidance for responders’ leaflet series.

The book will interest researchers and practitioners of emergency management, as well as those touched by disaster. As the authors point out, those without personal experiences of disaster, cannot fully comprehend the experiences, needs and challenges faced by survivors and the bereaved. The book provides examples of situations where officials have either inadvertently or wilfully neglected to listen to those affected by disaster and engage them in recovery processes. Eyre and Dix note that ‘Many of us feel that however terrible the disaster that changed our lives, what happened in the aftermath has made living with it harder instead of easier’ (p. 45). For example, developments in forensic science mean that relatives are rarely involved in victim identification and bodies of the deceased are often released after lengthy delays: ‘Psychologically, this is too late for many relatives to spend time with the deceased and to feel part of their “final journey”’ (p. 171).

The book provides insights into the ‘common bond’ that brings those touched by disaster together. A strong message is that people resent being told to ‘move on’ from their experience: ‘Unlike other friends, who share your pain but wish you to feel better and get beyond it, friends from the disaster appreciate that your life has been altered forever, and that it is not possible to go back to the way you were before’ (p. 19). While this may be a truism, it is an important reminder at a time when emergency management is fixated on ill-defined and poorly understood notions of resilience that emphasise self-reliance and returning to ‘normal’ (see Welsh2 for in-depth discussions of resilience concepts and policies).

Overall, Collective Conviction: The Story of Disaster Action provides valuable insights into the experiences and needs of those affected by disaster. Its strengths lie in the detailed history and firsthand accounts of the organisation and its activities. Understandably, most of the material testifies to Disaster Action’s value and achievements. Greater inclusion of perspectives from individuals or organisations that were initially critical of, or challenge, their activities may have provided important lessons for emergency management organisations. Despite this, the book offers profound insights into the challenges faced by those affected by disaster and the often simple things that officials can do to make the experience easier.

1 Disaster Action. At: www.disasteraction.org.uk/.

2 Welsh M 2014, Resilience and responsibility: governing uncertainty in a complex world. The Geographical Journal vol. 180, no. 1, pp. 15-26.