Members of the public are now acknowledged as important players who can provide much of the information, context, and many of the pathways for communication around disasters. This shift is reflected in the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience, which states:

In a disaster resilient context, the focus of communication requires a shift in emphasis from top-down messages to engaging individuals and communities at the grass roots level so they can understand disaster risks and share ownership of managing those risks... (National Strategy for Disaster Resilience 2011)1

In recent years there has been an acknowledgement from leaders of response-focused organisations that communication during emergency events may be more important than the response activities themselves.

While focus on words and language and their ability to effect action has not been extensively examined in the field of emergency management, it has been in other fields such as civil rights, criminology and gender studies. Time and time again, language use has been shown to influence behaviour and actions (Alter 2013, Coates 2007).

As part of a 2013 Fulbright scholarship, Bob Jensen, the former Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security in the U.S.A. made a number of presentations to emergency managers in Australia, sharing his experiences from a number of different disasters when working with Federal Emergency Management Agency of the United States (FEMA). On a number of occasions he stated, ‘When we [FEMA] stopped calling people “victims”, it changed how we worked with them.’ Jensen’s point indicated that by making changes to language, substantial changes to attitude and behaviour could be achieved.

In order to explore this, a survey was designed to examine the way that language used to describe the different players in emergency situations shapes the behaviour of emergency managers. The three ‘titles’ tested were:

These three titles, or labels, are commonly used within emergency management policy, arrangements, handbooks and training. The paper-based survey (completed anonymously) was issued to attendees at the 2014 Emergency Media and Public Affairs (EMPA) conferences in Auckland and Canberra.

The EMPA conference has been running in Australia since 2008, brought to life by public affairs and emergency communicators after Cyclone Larry. The conference is a forum where emergency communicators can share experiences and learn from each other. In 2014 an additional EMPA conference was held in New Zealand. Participants at these conferences were invited to complete the survey. A total of 49 were collected in Auckland and, a week later, participants at the Canberra EMPA conference completed 69 surveys. EMPA conference participants represent emergency management agencies, military, government, non-government organisations, research institutions, media organisations, and private sector organisations. Conference participants had an interest in communications and emergency management, are generally highly educated, and represented a balanced gender mix. There was no significant difference between the responses received from New Zealand participants and those from Australia.

This activity was not designed to generate quantitative data nor to be statistically analysed. Rather, it was an engagement activity and a quick test to see if any patterns emerged. It was also an exercise for participants to actively question their attitudes and assumptions when particular words are used. The feedback from participants provided an interesting insight into some of the attitudes prevalent among those in the emergency management sector.

While the words ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ have not been extensively debated in the emergency management context, they have been debated in relation to international development, conflict and violence. This history of the two words helps explain the narrative and character around them, which is part of everyday language.

The word ‘victim’ is a derivative of the Latin word victima, meaning sacrificial animal. The oldest record of using the word to refer to a human occurred during the Renaissance period in reference to Jesus Christ. Following this, the term began to be used more colloquially to refer to those suffering innocently from bad luck or other people’s criminal behaviours (Van Dijk 2008). The origins of some of the traits that are given to victims today—blameless, passive and needy—can be linked to this time. Many modern European, Asian and Arabic languages have more formally adopted ‘victim’ to refer to someone who has had a crime or offence perpetrated against them. While originally used in criminology as a neutral term to refer to a person who has suffered an act of crime, the word ‘victim’ has become increasingly loaded (McLeer 1998). Sexual violence activists often reject the term because of its implied passivity and weakness (Leisenring 2006) and aid agencies that portray end-users as ‘victims’ can be criticised for being paternalistic and inflammatory in their portrayal of helplessness in order to increase donations. The deliberate ‘victimisation’ of aid recipients for gain is sometimes cynically referred to as ‘poverty porn’ (Cameron & Haanstra 2008, Nathanson 2013).

The term ‘survivor’ is used in many different contexts. A rise in the term ‘survivor’ was seen in the 1960s and 1970s and was used by groups of people who had previously been portrayed as weak or helpless. These included those who had survived the Holocaust, sexual assault, rape and incest, and people affected by health conditions such as cancer. In the same era the word was used increasingly in psychotherapy, where the ultimate aim of a therapist was to assist ‘victims’ to become ‘survivors’. The term ‘survivor’ has been cast as an opposing identity to that of the victim. While both characters may have undergone something painful or traumatic that was outside of their control, the victim is seen to be immobilised and defeated by the experience, while the survivor rises above the adversity they face (Orgad 2009).

While other terms are used in emergency management, victim and survivor are two of the most prevalent. Other titles include ‘community member’, ‘resident’, ‘client’, ‘beneficiary’ and ‘service user’. Each of these terms presents their own challenges (e.g. they may not represent people who are affected by a disaster but are not living in the geographic area, people who fall outside the scope of the agency responsible for that geographic area, people who do not use [or feel as though they have benefited from] external services). Discussion regarding these terms falls outside the scope of this paper.

EMPA conference attendees were asked to list five words or sentences that described a disaster victim, a disaster survivor, and emergency management personnel. They were then issued a list of 38 words and sentences; some describing traits or characteristics and others describing actions. They were asked to identify which of the word and sentences correlated to their understanding of the disaster victim, the disaster survivor, and emergency management personnel (Table 1).

While the responses given by the participants were reasonably predictable, considering the focus of shared responsibility in Australian and New Zealand emergency management policy the trends that emerged were very interesting.

Table 1: Most commonly used traits when participants were asked to select words and sentences from a list to describe roles in emergency situations.

| Role ‘title’ | Words selected |

|---|---|

Disaster victim |

Distressed Vulnerable Traumatised Afraid Worried |

Disaster survivor |

Resilient Lucky Strong Resourceful Traumatised |

Emergency management personnel |

Action oriented Practical Resourceful Informed Capable |

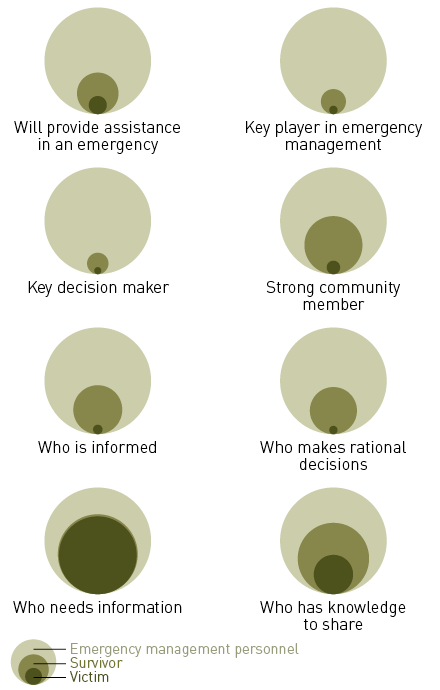

Figure 1 shows relational diagrams indicating responses by participants to questions about knowledge and role.

There were two main trends that emerged from the responses that warrant further investigation. The first was how differently emergency management personnel viewed themselves and their colleagues compared to victims and survivors. The results of this exercise highlight that the perception of emergency managers may still be skewed towards a belief that emergency management personnel have superior knowledge, behaviour and skills to the rest of the community. These attitudes are not reflective of the increasing focus on shared responsibility in emergency events by Australian and New Zealand emergency management leadership. Key documents such as the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience emphasise that enhanced community resilience in emergency management requires a shift from reliance on top-down official responses to increased community and grassroots-generated activity. Without dismissing the hard-earned expertise of many professionals in the field, such a dramatic difference in the regard for the skills and knowledge that others in the community can bring to these situations makes for a difficult starting position for a genuine and respectful shift from top-down directives to shared responsibility.

The second emerging trend from the responses was the stark difference in the perception of ‘victim’ compared to ‘survivor’. Participants consistently considered victims to be weaker, less rational, less informed and less knowledgeable than survivors. A simplified analysis would indicate that participants viewed survivors through a ‘strengths-based’ lens, while seeing victims through a ‘deficit’ lens. On an optimistic note, this may indicate that with deliberate changes to language, combined with improved education for emergency managers, and stronger community partnerships, profound shifts may be realised with reasonably small effort.

The trends that emerged from this simple activity indicate that emergency management planners, practitioners and communicators could learn from other sectors such as health and community development, where language has undergone a deliberate change.

If the emergency management sector is truly committed to sharing responsibility to encourage more resilient communities, cultural changes as to how community members are perceived by the sector will need to happen first. Sector leaders and communicators can lead these changes by reflecting the importance of working with community members as peers, acknowledging the skills and resources that people outside the sector can bring, and encouraging these changes within their organisations. Deliberate changes to the language we use may be a reasonably pain free but significant step that assists with these changes becoming reality.

Alter A 2013, The Power of Names. The New Yorker.

Cameron J & Haanstra A 2008, Development Made Sexy: How it happened and what it means. Third World Quarterly, vol 29, no. 8, pp. 1475–1489.

Coates L 2007, Langauge and Violence: Analysis of Four Discursive Operations. Journal of Family Violence, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 511–522.

Leisenring A 2006, Confronting ‘Victim’ Discourses: The Identity Work of Battered Women. Symbolic Interaction, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 307–330.

McLeer A 1998, Saving the victim: Recuperating the language of the victim and reassessing global feminism. Hypatia, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 41–55.

Nathanson J 2013, The Pornography of Poverty: Reframing the Discourse of International Aid’s Representations of Starving Children. Canadian Journal of Communication, 38, pp. 103–120.

Orgad S 2009, The survivor in contemporary culture and public discourse: A genealogy. The Communication Review, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 132–161.

Kate Brady is the National Recovery Coordinator for Australian Red Cross Emergency Services. She is undertaking her PhD in disaster recovery with the University of Melbourne.

1 National Strategy for Disaster Resilience. At: www.ag.gov.au/EmergencyManagement/About-us-emergency-management/Pages/National-strategy-for-disaster-resilience.aspx.