Many disciplines contribute to the field of emergency management and the contemporary literature reveals a grassroots, community-development approach to recovery and building resilience. Community-development approaches ‘seek to empower individuals and groups by providing them with the skills they need, to take collective action to effect change, and to generate solutions to common problems’ (United Nations 2001). This approach is increasingly recognised by emergency management academics (Mileti 1999, Paton & Johnston 2001, Smit & Wandel 2006, Norris et al. 2008, Mulligan & Nadarajah 2012) and practitioners (Attorney-General’s Department 2003). In an emergency management context, recovery is often conceptualised as ‘returning to normality’ (Deloitte 2013 p. 5), which ‘neither captures the changed reality after disasters nor encapsulates the new possibilities’ (Dufty 2012, p. 40). Resilience on the other hand not only considers the ‘capacity of communities to absorb shocks, retain their basic function and structures and bounce-back’ (Kirmayer et al. 2009) but also the ability of communities to thrive in the face of disaster (Coles & Buckle 2004, Maguire & Hagan 2007). This perspective seeks to understand positive responses to adversity at the individual and community level (Cutter et al. 2008, Paton & Johnston 2001) and advocates for ‘a new conceptualisation of normal’ (Norris et al. 2008, p. 132).

Every year, Australian communities face devastating losses caused by natural disasters (COAG 2011). During 2010-11, the El Niño Southern Oscillation climate phenomenon caused the strongest La Niña pattern since 1974 (Bureau of Meteorology 2011a) bringing above-average wet weather to Queensland. Significant flooding followed by the impact of Tropical Cyclone Yasi, led the then Premier Anna Bligh to declare ‘75% of Queensland a disaster zone’ (cited in AAP/One News 2011). On 6 April 2011, as a result of extensive damage, the Australian and Queensland governments announced funding for a $40 million Community Development and Recovery Package. Five days later, the National Strategy for Disaster Resilience was endorsed; an approach that recognises that ‘individuals and communities need to be self-reliant and better prepared to take responsibility for the risks they live with’ (COAG 2011).

Australia is not alone. Building and enhancing disaster resilience is a key strategic goal for governments around the world, evidenced by the Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015 (UNISDR 2005) and the recently adopted Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (UNISDR 2015).

The 2010-11 ‘Summer of Disasters’ and the consequent activation of the Community Development and Recovery Package in Queensland created a unique and unprecedented opportunity to evaluate perceptions of participants as to whether a community development approach, delivered by local government post-disaster, has been successful in helping communities recover and in identifying the degree to which adaptive strategies have been used to build capacity and resilience. Recommendations to encourage learning from both the successes and shortcomings of Queensland’s inaugural implementation are identified.

The study employed a mixed-methods approach to collect accurate, contextual data on implementation in Queensland2. Tablelands Regional Council was selected for the case study to provide a ‘real life’ example of how theory, policy and practice converge (Yin 2011). A focus group in the case study area explored projects implemented at the community level to elicit rich, qualitative data from residents on their experiences of the program. Purposive sampling targeted seven community disaster teams, formed under the auspices of this program. Eight residents participated in the focus group (75 minutes) and a further four participated remotely, providing written responses to questions posed at the session.

Another method of inquiry was to conduct semi-structured interviews with community development officers employed under the package (n=5). These in-depth interviews (average 90 minutes) explored worker perspectives and experiences with regards to program implementation at the local government level in Far North Queensland. Interviews were also undertaken (n=3) with the organisations responsible for administering the funding to explore their perspective on strategic implementation across Queensland. The final method of inquiry was an online survey3 that was sent to every community development officer employed under the package in Queensland (n=22). The survey questions built on the themes identified from the focus group and interviews and took around 20 minutes to complete. A response rate of 50 per cent (n=11) was achieved that helped validate the results and provide broader perspective.

Data collection and analysis occurred simultaneously. The focus group and interviews were recorded (audio) and later transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were read in their entirety several times to identify key words and phrases and were coded (Auerbach & Silverback 2003) to identify trends, organise ideas, and to assist with comparing and contrasting identified approaches, methods and practices. The continual synthesising and repeated reorganising and coding of data resulted in a good understanding of the themes characterising the research. The mixed-methods approach ensured consensus and validity across multiple data sources (interviews, focus group and survey) that strengthens the reliability of the findings through data triangulation (Guion, Diehl & McDonald 2011).

All 73 local governments received some funding under the Community Development and Recovery Package. The councils targeted for this research were the 17 that received funding under the Community Development and Engagement Initiative (CDEI) component; the councils deemed ‘hardest hit by the flood and cyclone disasters’ (Queensland Reconstruction Authority 2011, p. 12). The small sample size involved in this study reflects qualitative research methods. However, themes were validated across multiple data sources with strong links to previous studies on community resilience. The results are not claimed as indicative of all participants in the program and it is recognised that other communities, regions, states and nations need to consider the recommendations identified in their own context.

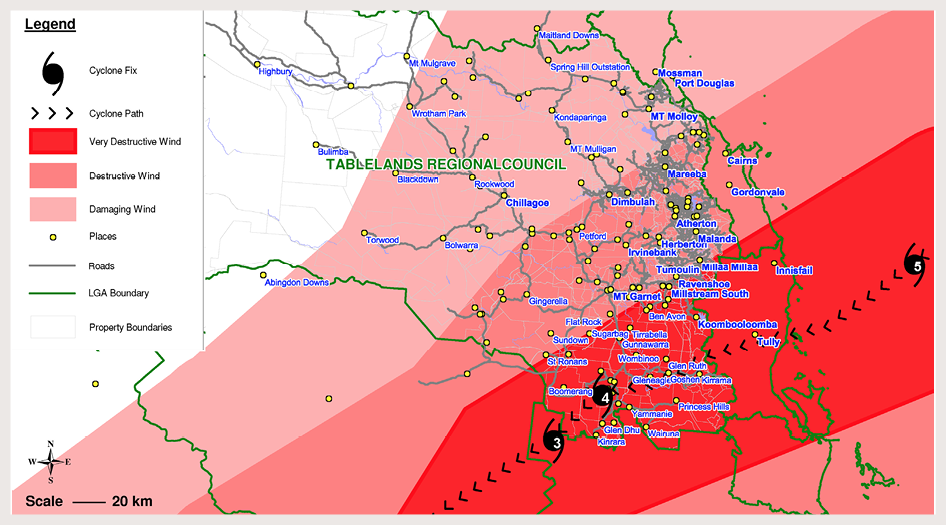

Tablelands Regional Council, located 100 km west of Cairns in Far North Queensland has a population of 43 727 people, dispersed across 65 008 km2 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011)4. On 3 February 2011, very destructive winds from Tropical Cyclone Yasi hit the remote southern area of the region (Figure 1) causing severe damage to 34 cattle stations. Fallen trees blocked access roads, destroyed cattle yards and damaged thousands of kilometres of fencing that led to problems with mustering and straying stock. Two homes in the region lost roofs and extended loss of power and communications hampered the recovery efforts of small business (Tablelands Regional Council 2011).

Figure 1: Tropical Cyclone Yasi impact on Tablelands Regional Council local government areas.

Source: Tablelands Regional Council

Tablelands Regional Council received $700 000 grant funding under the Community Development and Recovery Package. Exemplar projects delivered in communities were identified as the Community All-Hazard Disaster Plans and associated Skills and Capability Training Program (CDO, Community Members). The plans involved community members determining local responses to disasters (Walia 2008) and in ‘formalising what already happens in smaller communities [by] identifying resources in the local area that can be deployed to assist the community’ (CDO, Community Members). During this project, seven community all-hazard disaster plans were developed by residents and adopted by the Local Disaster Management Group. Additionally, community members were sponsored to obtain chainsaw tickets (n=284), first aid qualifications (n=246) and attend numerous other skill training courses for example, radio communications and leadership (n=798). In many communities, residents initiated their own projects. The Disaster Information Notification Network is one example where a proactive resident established an email network to communicate with 300 other residents on emergency-related issues.

The case study results demonstrate that the Tablelands region is proactively supporting a whole-of-community approach to emergency management and has implemented initiatives aimed at empowering individuals and communities to build their own resilience. The approach recognises that ‘people need to be empowered, actually encouraged to shine in times of disaster’ (Community Member) and that while ‘local government is the lead agency, local communities can self-help to a certain extent by commencing recovery operations until external resources arrive’ (CDO, Community Member). These projects clearly link to the community resilience literature covering areas such as hazard and risk awareness (Walia 2008), social support and networks (Dufty 2012, Pooley, Cohen & O’Connor 2010), community competence (Dufty 2012, Pooley, Cohen & O’Connor 2010), and sense of community (Pooley, Cohen & O’Connor 2010, Veil 2008).

The program was developed from research into ‘ways in which community development approaches…had aided other places in Australia and around the world’ (Funding Body #7). It was a ‘welcomed program’ (CDO #2, 6, Community Members) aimed at ‘supporting communities to reconnect, heal, remember and move on from the events’ (Funding Body #8) and ‘to assist with preparedness and growing resilience’ (CDO #2, 3, 6). The importance of ‘grassroots activities’ was acknowledged (CDO #2, 6) and it was recognised that ‘outcomes would be better, if driven by the community’ (CDO #3, Community Members). These findings infer that participants had a good understanding of the intent of the program.

Results revealed that community warden schemes, preparedness packs, resilience toolkits, resilient leader networks, special-needs resources and capability training programs were delivered across Queensland. These projects clearly value-add when considered in a disaster resilience context. To help validate findings, survey respondents were asked whether their key projects linked to categories extracted from the community resilience literature. Table 1 shows the results, indicating that projects delivered can be linked to the normative conditions associated with competent and resilient communities.

Table 1: Participant perspectives on how exemplar projects implemented in their communities link to community resilience.

| Category / normative condition | Community resilience literature | Proportion of responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Capacity Building | Ireni-Saban 2012 | 19 |

| Education and Training | Walia 2008 | 19 |

| Social Connectedness and Empowerment | Dufty 2012

Pooley, Cohen & O’Connor 2010 Norris et al. 2008 |

15 |

| Sustainability | Tobin 1999 | 12 |

| Awareness of Hazards and Risk | Walia 2008 | 8 |

| Health and Spiritual Wellbeing | Fernando 2012 Walsh 2007 | 8 |

| Adaptation Skills | Smit & Wandel 2006

O’Sullivan et al. 2012 |

4 |

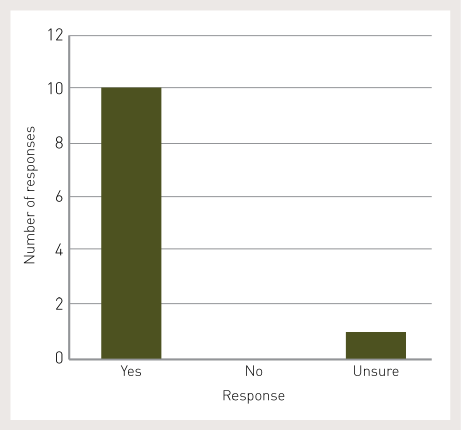

One funding body (#4) revealed that ‘320 fantastic and innovative projects had been rolled out across the State and almost 300 000 points of engagement recorded across the program’. While claims of success need to be considered in the context of the role of the funding to garner support for the program and boost positive opinion for the state government, results from the survey data indicate that 91 per cent of participants thought that a community development approach to disaster recovery and building resilience had proven effective in their own community (Figure 2). This perspective was also supported in the practitioner interviews. The remaining nine per cent of survey participants stated they were unsure because the outcomes had not yet been tested in a real event5.

The program was identified as ‘the largest investment of funding into this type of community development practice’ (Funding Body #7). Survey respondents were asked to identify implementation costs for exemplar projects in their communities. The results indicated 60 per cent of projects cost less than $15 000 to implement, demonstrating that resilience-building initiatives are not necessarily costly. Data revealed that the funding was beneficial, but the real value was identified as the human resource embedded within councils to drive projects at the community level (Funding Body #7, CDO #1, 3, 6, Community Members). A ‘lack of human resource to drive initiatives’ (CDO #2) and a ‘lack of budget’ (CDO #6) were identified as possible reasons that most councils were not actively engaged in delivering community-based disaster resilience building initiatives to communities prior to the commencement of the program.

The tendency of governments to ‘throw resources at disasters after the event...’ (CDO #3) was recognised by participants. This criticism of funding is not new (Board of Natural Disasters 1999). Some workers considered the money ‘a bit of a hindrance’ (CDO #3) in that it created ‘reliance on funding and built dependency’ (CDO #2). Projects explored in this context included movie nights, fishing competitions, music festivals and pamper nights. While such activities met the terms of the funding agreement, because the ‘social inclusion aspect encouraged people to participate in community-based activities’ (CDO #2), the link to disaster resilience was identified as tenuous as it is difficult to envisage how such activities build capacity to deal with future natural hazard events. The need for psycho-social bonding activities is not disputed but the delivery of programs by local governments could establish a precedent and possibly create unrealistic expectations for future events. This indicates that recovery activities need to be viewed within a broader framework of resilience and that local governments need to engage in activities that do not undermine or potentially create unintended negative consequences for a community’s future resilience. Nor should they place further strain on the limited resources available for response, recovery and reconstruction efforts. A related theme that emerged was the limited interaction between the disciplines of emergency management and community development where there is no clear linkages or cross-pollination of ideas at a state or local government level (CDO #1, 3, Funding Body #8). It is argued that improved collaboration between practitioners may have helped to identify projects with the potential to inadvertently foster future expectation or reliance on government funding or services.

Another consistent theme related to ‘evidence of disconnect’ (Funding Body #7, CDO #1, 3, 6). There was ‘pressure to get the money out quickly and so existing relationships with councils were used [resulting in] administrative complexities that hadn’t been anticipated’ (Funding Body #8). The ‘three separate organisations administering the funding program, that ultimately reported to the same steering committee, appeared to have vastly different requirements’ (CDO #3) and there was significant ambiguity in funding agreements (CDO #1, 2, 6). Workers unanimously identified high reporting demands and limited timelines. Some perceived the program to be about compliance as opposed to achieving the best possible outcomes for communities (CDO #2, 6).

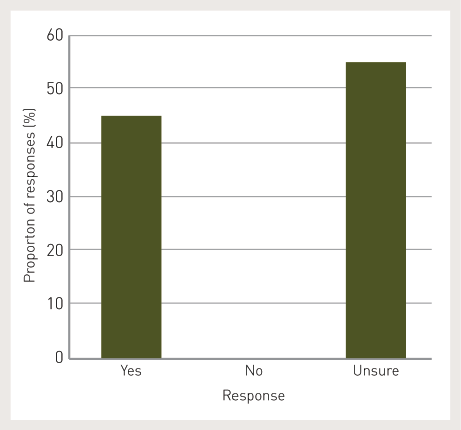

NDRRA funding is offered for a maximum of two years with no longevity of programs or workers, revealing the final theme—sustainability. Participants recognised that community development is a long-term approach and many felt the program was ‘just starting’ or ‘finishing too early’ (CDO #2, 3, 6, Funding Body #7). To validate results, survey participants were asked whether the projects they had implemented were sustainable once the funding ended. Only 45 per cent of respondents said yes and while nobody said no, 55 per cent of respondents stated they were unsure, demonstrating that a significant proportion of projects have the potential to fail in the longer-term (Figure 3). This is a key risk because ‘there is a danger of the program being a waste of money’ (CDO #3). ‘If [the program] is not sustained, you might get a year or two of benefit, but without a driving force it will probably fade away’ (CDO #5).

Future funding models for disaster management need a stronger focus on prevention and preparation, as opposed to the current model. The NDRRA predominantly focuses on the relief and recovery phases of an event. It is recommended that the Community Development and Recovery Package be removed from the NDRRA. The NDRRA is suited to the relief and recovery context because its design has no longevity. This is detrimental to resilience because resilience requires an ongoing, sustained effort and continual development and nurturing. The model of financing disasters after they have occurred is flawed and is systemically contributing to creating reliance on relief and recovery funding. The role of government is not to try to ‘fix’ disasters. Instead, local governments need to be supported to adopt a whole-of-community approach to emergency planning and management. Local governments need to invest in community development approaches that enhance resilience while building capacity to support members of the community should the effects of an event be beyond their capacity to cope.

The administrative complexities associated with the inaugural implementation of the Community Development and Recovery Package need reviewing to streamline future implementation. It is recommended that issues relating to ambiguity of the funding agreements, unification of delivery and reporting requirements to three different funding agencies, and support for workers and the limited timelines are addressed prior to any future implementation of the program under an alternative funding model. Furthermore, a clear set of monitoring indicators and outcomes need to be outlined in the development phase of such programs and for each project so that benefits can be clearly identified and any unintended consequences mitigated.

Further improvements relate to the limited interactions between the disciplines of emergency management and community development practitioners identified during the program. Recovery and resilience are distinctly different strategies, but need to be integrated holistically at a local government level to ensure the best possible outcomes for communities. A partnership approach between emergency management and community development professionals (with a shared vision and common approach to building resilience to natural hazards) will help strike the correct balance between recovery and resilience-building activities. Improved collaboration at practitioner level will also help identify and resolve potential conflicts that arise. This ensures programs do not create negative or unintended consequences for a community’s future resilience, or inadvertently create future expectations or reliance on government funding or services.

The funding was a significant investment on a relatively untested program. Despite a number of challenges, it has achieved some levels of success in enhancing community resilience, at least in the short-term. It has helped people come together on projects that enhanced their skills and knowledge and built self-confidence, community capacity and cohesion. There are numerous case studies from around the world about building resilience to disasters using a community-development approach and this study builds on that research. It provides further evidence for a whole-of-community approach to emergency management. Adoption of these recommendations will inform future decision-making and policy direction and lead to greater opportunities to foster longer-term community resilience to natural hazards in Queensland.

AAP/One News 11 January 2011, Disaster in Queensland: Ten dead, 78 missing, grave concerns for 15. At: http://tvnz.co.nz/world-news/disaster-in-queensland-ten-dead-78-missing-grave-fears-15-3996332 [14 July 2012].

Auerbach CF & Silverback LB 2003, Coding 1: The basic ideas. Qualitative Data (pp. 31-38). New York & London: New York University Press.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011, Tablelands (R) 2011 Census Quick Stats. At: www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/LGA36810 [14 April 2012].

Attorney-General’s Department 2003, Community development in recovery from disaster. Canberra: Emergency Management Australia.

Board of Natural Disasters 1999, Mitigation Emerges as Major Strategy for Reducing Losses Caused by Natural Disasters. Science, New Series 284 (5422) June 18, 1999, pp. 1943-1947.

Bureau of Meteorology 2011a, The 2010-11 La Niña: Australia soaked by one of the strongest events on record. At: www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/feature/ENSO-feature.shtml [18 August 2012].

Council of Australian Governments 2011, National Strategy for Disaster Resilience. Attorney-General’s Department.

Coles E & Buckle P 2004, Developing community resilience as a foundation for effective disaster recovery. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 6-14.

Cutter SL, Barnes L, Berry M, Burton C, Evans E, Tate E & Webb J 2008, A place based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change 18, pp. 598-606.

Deloitte Access Economics 2013, Building our nation’s resilience to natural disasters (white paper). Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities, ACT.

Dufty N 2012, Using social media to build community disaster resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 40-45.

Fernando G 2012, Bloodied but unbowed: Resilience examined in a south Asian community. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 82(3), pp. 367-375.

Guion LA, Diehl DC & McDonald D 2011, Triangulation: Establishing the validity of qualitative studies. USA: University of Florida.

Ireni-Saban L 2012, Challenging disaster administration: Toward community-based disaster resilience. Administration and Society 44(4), pp. 1-23.

Kirmayer LJ, Sehdev M, Whitley R, Dandeneau SF & Isaac C 2009, Community resilience: Models, metaphors and measures. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 7(1), pp. 62-117.

Maguire B & Hagen P 2007, Disasters and communities: Understanding social resilience. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 16-20.

Mileti DS 1999, Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States (1st ed.). USA: Joseph Henry Press.

Mulligan M & Nadarajah Y 2012, Rebuilding community in the wake of disaster: Lessons from the recovery from the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka and India. Community Development Journal, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 353-368.

Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF & Pfefferbaum RL 2008, Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities and strategies for disaster resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1-2), pp. 127-150.

O’Sullivan TL, Kuziemsky CE, Toal-Sullivan D & Corneil W 2012, Unravelling the complexities of disaster management: A framework for critical social infrastructure to promote population health and resilience. Social Science & Medicine 2012. At: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.040.

Paton D & Johnston D 2001, Disasters and communities: Vulnerability, resilience and preparedness. Disaster Prevention and Management, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 270-277.

Pooley JA, Cohen L & O’Connor M 2010, Bushfire communities and resilience: What they can tell us? Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 33-38.

Queensland Reconstruction Authority 2011, Operation Queenslander: Rebuilding a stronger, more resilient Queensland. At: www.qldreconstruction.org.au/publications-guides/resilience-rebuilding-guidelines/rebuilding-astronger-more-resilient-queensland [10 July 2012].

Smit B & Wandel J 2006, Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3) pp. 282-292.

Tablelands Regional Council 2011, Tropical Cyclone Recovery Plan. At: www.trc.qld.gov.au/disaster-management/post-eventinfo/ [18 January 2013].

Tablelands Regional Council 2012, Community All-Hazard Disaster Plan Template V2. At: www.trc.qld.gov.au/disaster-management/disaster-plans [21 January 2013].

Tobin GA 1999, Sustainability and community resilience: The holy grail of hazards planning? Environmental Hazards, (1) pp. 13-25.

Twigg J 2007, Characteristics of a disaster-resilient community: A guidance note. UK: Department for International Development. At: https://practicalaction.org/docs/ia1/community-characteristics-en-lowres.pdf [9 July 9 2012].

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction 2005, Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters [extract from the final report of the world conference on disaster reduction].

United Nations Terminology Database 2001, UNTERM. At: http://untermportal.un.org/portal/welcome [17 March 15].

Veil SR 2008, Civic responsibility in a risk democracy. Public Relations Review, vol. 12, pp. 387-391.

Walia A 2008, Community based disaster preparedness: need for a standardised training module. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 68-73.

Walsh F 2007, Traumatic loss and major disasters: Strengthening family and community resilience. Family Process Journal, 46(2), pp. 207-227.

Yin R 2011, The role of theory in doing case studies. Applications of case study research, pp. 27-48. Washington DC: Sage.

Sarah Dean is an emergency management practitioner with 15 years experience working for local government in Australia, the UK and the Caribbean. Sarah is interested in community-led disaster response and recovery and community resilience. She graduated from Charles Sturt University, NSW with a Master of Emergency Management.

1 Category C relates to assistance for severely-affected communities, regions or sectors when the impact of an event is severe. It includes clean-up and recovery grants for small businesses and primary producers and/or the establishment of a Community Recovery Fund.

2 The research was undertaken between December 2012 and April 2013 (CSU HREC Approval #110-2012-17).

3 Survey participation was voluntary and anonymous.

4 This research was undertaken during 2013. On January 1 2014, the new Mareeba Shire Council was formed as a result of de-amalgamation from the Tablelands Regional Council.

5 Anecdotally, there is some evidence to suggest enhanced resilience was demonstrated in areas re-affected by flooding in 2013 and again during Tropical Cyclone Ita in 2014.

A version of this paper was presented at the Australia & New Zealand Disaster and Emergency Management Conference in May 2014.