By Steve Glassey, MEmergMgt FEPS CEM®

Even before an After Action Report is compiled, we know that, if things did not go well, the same issues of leadership, role clarity, communications, and training are likely to rear their repetitive heads. In New Zealand, numerous incidents including the Napier Earthquake (1931), Ballantyne Fire (1947), Wahine Ferry Sinking (1968), Pike River Mine Disaster (2010) and the CTV building quake collapse (2011) all share similar lessons learned—but are they really learned? Each inquiry, though different in circumstance and environment, makes recommendations—recommendations that have been previously identified, but never institutionalised. We promise the affected families and the public that these deficiencies will never be repeated—but they are. Why do we make the same mistakes, over and over throughout time? How often do we read historical After Action Reports? The lack of institutional and social memory could certainly be a factor, but how do we ensure that lessons identified are actually turned into lessons learned?

In a recent request for all After Action Reports for declared civil defence emergencies in New Zealand between 1960 and 2011 (n=170), only 56 (33 per cent) were provided, 80 (47 per cent) were unable to be located, 14 (eight per cent) were sourced from National Archive or private collections as the declaring authority did not have any records, seven (four per cent) were merged with other requests due to declaration overlap, and eight (five per cent) could only provide peripheral information about the emergency. Some requests took several weeks and even months to locate and some were withheld (rightly or wrongly) under Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987 exclusions. What this highlights is how can we learn lessons if we don’t even know what the lessons were if reports are non-existent? Even the Ministry of Civil Defence and Emergency Management’s ‘database’ of declared emergencies omits events and, despite the requirement to gazette each declaration, the Gazette Office was unable to provide a summary of declared events. What a mess!

Like a stone being dropped into a pond, the ripples fade the farther away from the point of impact; just like lessons learned. The closer (geographically, politically or emotionally) we are to the lesson identified, the more likely we are to know of it. We simply do not learn from our lessons and we need a mechanism to identify the issues in real-time during an emergency, not realising in hindsight that yet again, the lesson identified has been repeated. How can we move from a culture of identifying lessons, to actually learning them dynamically and in a sustainable fashion?

In New Zealand, the term ‘doctrine’ has started to emerge. It was formally introduced in the revised Coordinated Incident Management System (CIMS) manual (2014 edition) and defined as:

‘the body of principles and practices that guide an agency’s actions in support of their objectives. It is authoritative, but requires judgement in application’ (Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2014).

The section explaining ‘doctrine’ provides a flawed and over simplified model that assumes that doctrine informs training, which is applied in operations, which is updated from operational learning. There is no evidence to suggest this model is valid. In fact a workshop of experienced emergency managers (including military and civilian personnel) concluded that emergency management ‘doctrine’ was vague at best. If such a model is in effect, why do we repeat over and over the same mistakes operationally?

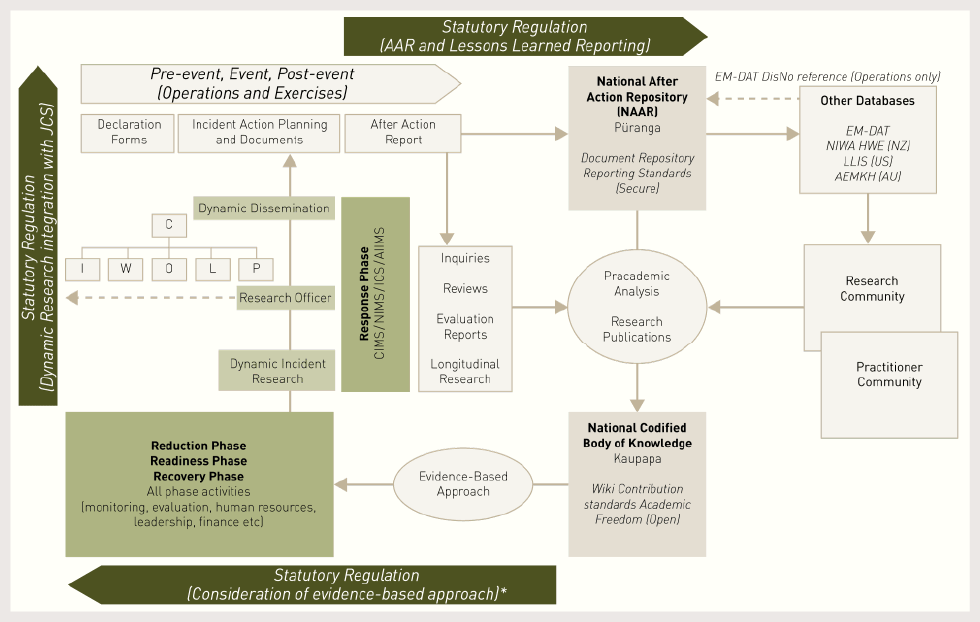

There are different types of doctrine including religious, political and military, the common characteristic being that they are written and codified—something that emergency management ‘doctrine’ is not. Who controls doctrine? Is it formal or informal? Do we have a codified body of knowledge for emergency management? Is it evidence-based, tradition or historically based? The continual use of ‘doctrine’ in emergency management is meaningless unless we define it—which, to date, we have not done. Evidence-based doctrine refers to a codified body of knowledge based on evidence—not political or preferential views. The Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor, Professor Sir Peter Gluckman has criticised New Zealand government officials for providing advice based on personal views, without any evidence (TV3 News 2013). Evidence-based doctrine ensures the codified body of knowledge is based on empirical research, not personal beliefs, opinions or agendas. However, doctrines are typically not updated in real-time, which is a flaw in their existence, particularly in an emergency management context. The development of an Evidence Based Dynamic Doctrine (Figure 1), uses active research during an emergency to inform, in real time, better decision making and reduce the size of the lessons identified loop.

* Statutory consideration of evidence-based approach requires authorities to consider an evidence-based approach. Where a final course of action is not consistent with an evidence-based approach, a statement of justification (e.g. lack of resources) must be disclosed.

C = Controller, W = Welfare, O = Operations, L = Logistics, P = Planning, I = Intelligence

The Evidence Based Dynamic Doctrine (EBDD) has five key elements:

Following the response (and later recovery) a standardised after action reporting system ensures all incidents are captured in a secure document depository, where other officials can access reports. Incident data can also be shared with international databases such as EM-DAT operated by the Centre of Research for the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). However, after Action Reports are subject to bias and are generally not independent. In New Zealand, there is no requirement for authorities who declare a state of emergency to compile an After Action Report, and even if they do, there is no document standard, nor obligation to share it with the rest of the emergency management sector. A regulatory instrument should be created to ensure that after action reporting is conducted in a standardised fashion and ensure these updates are centrally stored and shared securely within the sector.

The Pracademic analysis is jargon for the analysis of research and other sources of information that is conducted jointly by practitioners and academics. Often there is a significant divide between these two groups and the lack of any requirement for emergency managers to have higher education qualifications compounds this division. Using a panel of practitioners and academics, After Action Reports along with other sources of information (such as research projects, inquiries, evaluations) are codified into an online knowledge repository (such as a wiki), which is regularly reviewed. This approach encourages practitioners and academics to work closely together.

This codified body of knowledge (CBOK) is open and available to the public and end users. It is hosted in an academic environment to afford it academic freedom and to ensure it conforms to set contribution standards. It is this CBOK that is used in applying an evidence-based approach to emergency management, including in emergency management teaching curricula. Over time, the CBOK will grow in volume making it an up-to-date and authoritative source of evidence-based practices.

A regulatory instrument requires mandated organisations to consider an evidence-based approach, as ultimately, in a democratic environment, decisions are often made based on politics, not evidence. The regulatory instrument requires decision makers to make public disclosure when they are not taking an evidence-based approach and outline their justification to do so. This also protects policy makers as often they are constrained by budgets and this disclosure puts the decision-making back on communities to determine what they want from their community leaders. For example, if citizens are told there is no budget for an early warning system but their municipality is upgrading a swimming pool, citizens have a choice to advocate for the warning system or accept they will have a reduced level of warning. It is about encouraging communities to make informed decisions about the hazards they live with and choosing how best they are managed.

It also encourages policy makers to engage with communities through deliberative democracy. The evidence-based approach applies to all phases and cross-cutting themes in comprehensive emergency management. It means that from public education campaigns to human resource recruitment and selection, an evidence-based approach is taken. Pilot projects that may not be evidence-based can still continue to ensure innovative and creative solutions are trialled; however they would be done so in a structured and validated fashion, in which results would be formally evaluated through pracademic analysis to determine whether it is added to the codified body of knowledge.

An incident management team tests Standard Operation Procedures during Exercise Phoenix, June 2015 in Waitaki, New Zealand.

The system closes the loop, based on all the previous After Action Reports and research, starting at the time of a response. A research officer is embedded in the incident management team (generally in the Planning cell) who identifies critical evidence-based considerations for the Incident Management Team. The research officer primarily sources such considerations from the codified body of knowledge or uses their independent research skills to investigate novel problems. Their goal is to identify the issues while the incident is unfolding, rather than to identify problems after the fact in the post mortem phase. This creates real-time risk management within the incident management system, rather than researchers only being engaged after the response to review in hindsight areas for improvement, as has been the case traditionally.

Every time the journey is made around the evidence-based dynamic doctrine circuit, the lessons learned circle size reduces as previous mistakes and lessons should not be repeated. Additionally, the focus of the dynamic research should evolve from being less reactive, to being more proactive, with a reduction in the same issues being re-experienced during the response phase. As a result the research officer has more time to look at forecasted issues to resolve.

Without embedding dynamic research into the Incident Management Team, this model would only be an evidence-based doctrine (which is better than just a doctrine that is not necessarily evidence-based). The Dynamic Research process carried out by the research officer requires the model to be an Evidence Based Dynamic Doctrine, it provides real-time correction and support to incident planning to avoid the same mistakes from occurring time after time. It requires a special kind of researcher who has credibility and a personality compatible with front line responders. This requires specialised training for researchers, careful selection and plenty of exercising to create solid pre-event relationships so that research officers are seen as valuable contributors to the Incident Management Team, not as a hindrance with bad fashion sense and over philosophising in verbose academic ramblings.

The Evidence Based Dynamic Doctrine model creates an holistic solution that joins up fragmented important elements. We do have After Action Report repositories. We do have researchers talking to practitioners. We do try to have scientific advice in response, and we do endeavour to follow best practice. But we have been unable to draw the connections across these elements in a meaningful way.

In reality, we don’t produce lessons learned reports. They are more likely to be lessons identified reports. Although there may be recommendations, they are not always practical to implement due to financial, social, political, environmental, cultural or other considerations. Lessons learned is a misnomer.

We generally have the following types of lesson-related reports:

Lessons identified reports are the most common, though they generally lack any consistent format or content (unless part of a system like the Lessons Learned Information Sharing or LLIS operated by the US Department of Homeland Security). They are generally produced by the agency and highlight areas of improvement, though there should be a greater emphasis to include what went well too.

Lessons lost reports are those that have been compiled, but unable to be found or retrieved. The example of 47 per cent of New Zealand’s declared civil defence emergency reports since 1960 being inaccessible highlights the need for a centralised repository.

Lessons buried reports are not common, but they are the reports that contain criticism that is politically unpalatable and the agency goes to lengths to prevent the report from being disclosed. This however does create the need for discussion around what should be included in reports, the frankness of opinions and criticisms, and the tension between openness and public accountability through freedom of information instruments.

Lessons learned reports are rare. Though many agencies tout their After Action Reports as lessons learned reports, they are generally just lessons identified. Lessons learned reports generally take some years to truly compile as they not only show the lessons identified, but the changes recommended, implemented and, most importantly, evaluated.

In summary, lessons learned is a misnomer. We don’t really learn them, we state them. Over time social and institutional memory fades them into irrelevance. We have failed to learn them in a sustainable manner because we do not have a system in place to store, analyse, disseminate and dynamically apply them. The development of the Evidence Based Dynamic Doctrine aims to develop a philosophy around real-time correction and support to incident action planning during response, while providing an evidence-based approach across the phases of comprehensive emergency management.

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2014, The New Zealand Coordinated Incident Management System (2nd ed.) Wellington, New Zealand.

TV3 News 2013, Gluckman queries government policy advice. Retrieved April 26, 2014. At: www.3news.co.nz/Gluckman-queries-government-policy-advice/tabid/1607/articleID/311712/Default.aspx.