Much of what is known about pet owner behaviour in emergencies in an Australian context is informed by limited or anecdotal evidence, or media reporting of the actions, or inactions, of individuals. In the international disaster literature pet ownership is regarded as a risk factor most consistently associated with evacuation failure (Brackenridge et al. 2012, Heath, Voeks & Glickman 2001) and linked to unsafe acts motivated by a desire to rescue animals that have been left behind (Heath, Voek & Glickman 2000, 2001; Zottarelli 2010).

Generally, attachment to pets is high, with many people considering pets as members of the family (White 2012). The strength of this attachment is never more apparent than in the event of pet loss in disaster, with reports of prolonged and often unnoticed or unsupported grief (Blazina, Boyra & Shen-Miller 2011) and poor psychological outcomes, especially in the event of forced abandonment of pets during evacuation (Hunt, Al-Awadi & Johnson 2008). The roles pets and other animals may play in supporting post-emergency functioning and resilience-building are also vital. For these reasons, as well as the implications for public and responder safety during emergency, it is critical that they are considered in emergency management planning.

The primary emergency event, internationally, that led to increased attention to animal emergency management was Hurricane Katrina in 2005, in which more than 50 000 companion animals were abandoned and 15 000 were rescued. Irvine (2009) provides a compelling overview of the scale of the animal emergency management challenge and the film ‘Dark Water Rising’ (Shiley 2006) provides sobering documentary evidence. Post Hurricane Katrina research indicated that 44 per cent of non-evacuees who chose not to evacuate did so because they didn’t want to leave their pets. Soon after Hurricane Katrina the United States Senate passed the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act 2006, which requires states seeking Federal Emergency Management Agency assistance to make provisions for pets and service animals in their plans.

In Australia there is no equivalent requirement. Pet ownership levels in Australia are among the highest in the world, with around 63 per cent of households owning a pet (Animal Health Alliance 2013). The need to consider animals and their owners in emergencies has been increasingly accepted in Australia, prompted by large-scale disasters and reports from the 2003 ACT Bushfires Inquiry, 2011 Queensland Flood Commission of Enquiry, the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission, and the 2013 Tasmania Bushfires Enquiry. These reports all included references to the management of animals. Many emergency services organisations and other stakeholders involved with emergency management and animal welfare now have strategies and resources available to assist animal owners.

Although the requirement to address a range of issues associated with the management of animals and their owners in emergencies and disasters is now acknowledged in Australia there is a lack of systematic data or evidence available to inform these activities. New Zealand has a small body of research, with one study (Glassey 2010a) reporting that a substantial proportion of pet owners (56 per cent) would not evacuate without their pets and a larger proportion still (81 per cent) would be more likely to comply with evacuation if there were evacuation shelters that could cater for pets. This led to recommendations being made to improve animal emergency management (Glassey 2010b). In Australia research in this area is currently non-existent, although there is increasing discussion with Thompson (2013) positing that the strong bond people have with animals could be used to promote disaster preparedness. This current study was undertaken to assist in addressing the gap in Australian research. The study explores a range of issues around Australian pet owner emergency preparedness for their households and their pets, their actual or anticipated evacuation behaviours in the context of an experienced disaster or emergency, the sources of information used to gain assistance around the time of evacuation, and lessons identified from the experience.

A questionnaire was developed to assess pet owner characteristics, emergency and evacuation contexts, evacuation experiences and preparedness. To meet study inclusion criteria respondents needed to have experienced ‘a disaster or local emergency in which they evacuated, or considered evacuating their home’, to have been a pet owner at the time of the disaster, and to be aged over 18 at the time of completing the survey.

The survey was administered using the online survey-hosting platform SurveyMonkey™. A link to the survey with a short invitation to participate was distributed using a combination of social media (Facebook and Twitter), online and print media, and a University of Western Sydney media release. The link on social media was reposted by a number of animal rescue and similar special interest pages. Data were collected over an eight-week period (22 Jan – 22 Mar 2013).

The study was approved by the University of Western Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. H9993).

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS software (V.21). Simple descriptive statistics, frequencies and cross-tabulations, have been reported here to produce a concise overview of the survey findings.

In total, 352 pet owners met the study inclusion criteria and are represented in the analysis. The majority of the sample was female (89 per cent) and 86 per cent were aged between 25 and 64 years.

Respondents came from all states and territories with the largest groups from Queensland (51 per cent) New South Wales (25 per cent), and Victoria (12 per cent). Two-thirds of the sample lived in suburban and rural areas (35 per cent and 32 per cent respectively).

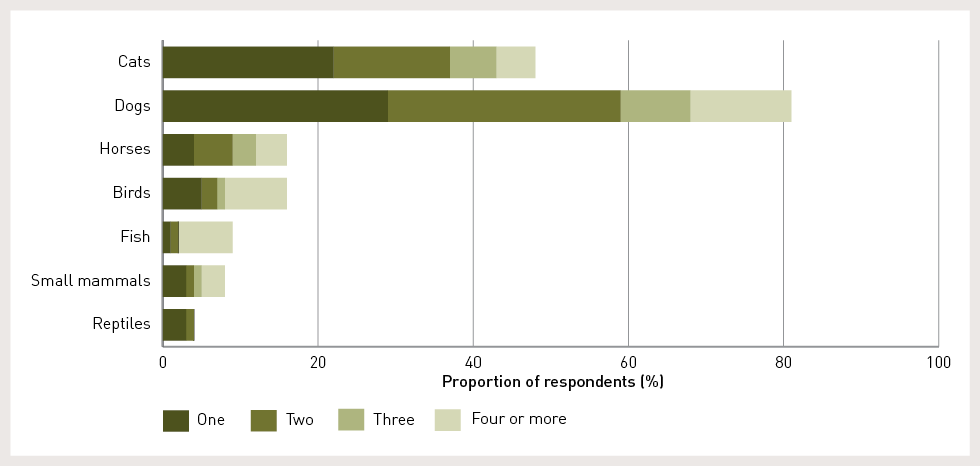

Respondents were asked about the composition of their pet ownership and their attitudes to their pets. At the time of the emergency, 79 per cent of respondents owned one or more dogs and 49 per cent owned one or more cats. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the numbers of pets owned by respondents.

Figure 1: Pet ownership composition at the time of the disaster.

Figure 1 shows the complexity of household pet ownership. In total, only 18 per cent of respondents owned one pet; the majority of those (72 per cent) owning a dog. Just over a quarter (26 per cent) owned only one animal type, but multiples of them, and the remainder (57 per cent) owned multiple types of animal. A small proportion of respondents (4 per cent) were running animal-related home-based businesses or enterprises that involved large numbers of animals. These were mostly breeding or rescue and rehoming enterprises, and a few respondents were wildlife carers.

Overwhelmingly, pet owners felt a high degree of responsibility for their pets and a strong attachment to them (with mean ratings of 9.84 and 9.76, respectively on 10-point scales for each). Most respondents strongly agreed that they considered pets to be part of the family (86 per cent), that their pets made them happy (86 per cent), and that they were great companions (88 per cent).

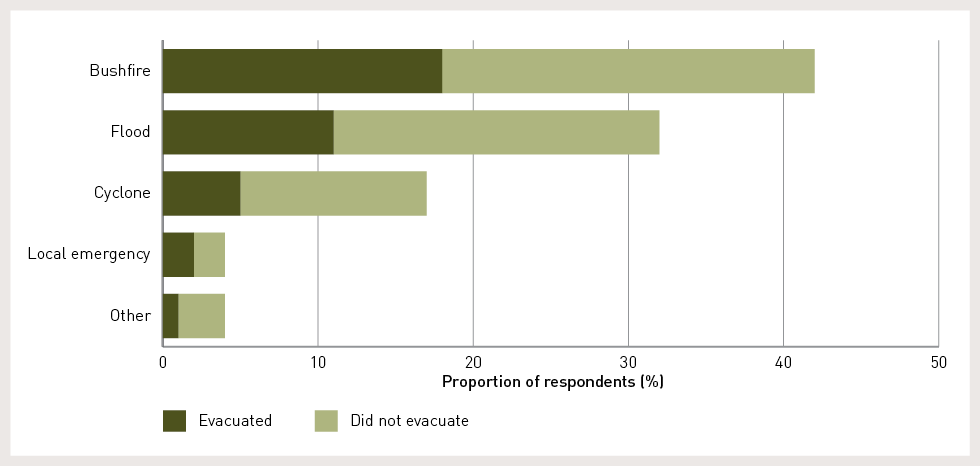

As data in this study do not relate to a single specific disaster or emergency event, evacuation behaviours are reported in relation to a range of hazard types. Figure 2 summarises the disaster and emergency situations encountered by respondents and their pets, i.e. the single event about which they provided information in the survey. This figure also includes data on the proportions that did/didn’t evacuate in that event.

Figure 2: Disaster and emergency situations reported by respondents and the proportions that did/didn’t evacuate.

With regard to the timing of these events, more than half (56 per cent) occurred since 2011, and more than 70 per cent since 2009. Most respondents provided details of the events they experienced, with the 2011 southeast Queensland floods, 2011 Tropical Cyclone Yasi, 2013 Bundaberg floods, and 2009 Black Saturday bushfires mentioned most frequently.

In response to these events, 31 per cent of respondents evacuated with their entire household, 6 per cent partially evacuated, 36 per cent prepared to evacuate but didn’t actually go, and 27 per cent didn’t evacuate or prepare to evacuate. Of those who reported that they were advised by authorities to evacuate (31 per cent) 70 per cent did so.

Just over a quarter of respondents (27 per cent) had less than three hours to evacuate. As would be expected, the hazard type influenced the amount of time available to evacuate; 60 per cent of those who experienced a local emergency and 23 per cent of those who experienced a bushfire had less than one hour to evacuate, whereas of those who experienced flood, 18 per cent had between three hours to a day to evacuate, and 24 per cent of those who experienced a cyclone had more than a day.

Over a half of respondents who evacuated (58 per cent) were away from home for less than two days, and a fifth were unable to return for two-five days (21 per cent), or more than five days (21 per cent). Again, the hazard type influenced how long participants were away from home. Approximately two-thirds of those who evacuated due to bushfire or cyclone were able to return in less than two days (67 per cent and 64 per cent, respectively) compared to only 37 per cent who experienced flood. Flood-impacted pet owners were the most likely to be away from home for more than five days (34 per cent) compared to those who experienced bushfire and cyclone (14 per cent and seven per cent respectively).

A total of 122 respondents evacuated (fully or partially) and data in this section relate to this subsample.

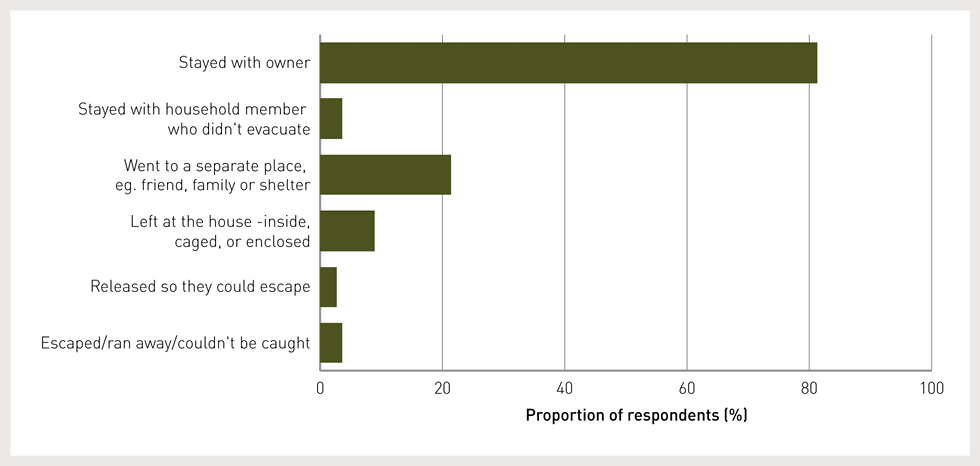

When people evacuated their homes many things happened to their pets. Figure 3 summarises what happened to the animals.

Figure 3: What happened to pets when households evacuated.

Respondents were asked why some pets weren’t evacuated with them. Comments included respondents not being able to catch or contain them, being told by emergency services personnel that they could not take their pets with them at the time of evacuation, or that they wouldn’t be able to take them to evacuation centres, that it was too hard to take them, that they had died, and that there were too many to take.

Over two-thirds of respondents who evacuated stayed with family or friends (69 per cent), and smaller proportions stayed at an evacuation shelter (five per cent), hotel/guest house (four per cent) or showground/campsite (three per cent). Those who stayed elsewhere (18 per cent) mentioned staying in cars/utes, with neighbours, and at schools or workplaces; some reporting they stayed in cars because evacuation shelters wouldn’t accept pets.

When asked about how owning pets influenced evacuation, significant proportions of the sample strongly agreed or agreed that having pets influenced where they went after evacuation (81 per cent), their decision about whether to evacuate (72 per cent), increased the stress of evacuation (68 per cent), and the mode of transport they used (66 per cent). In addition, having pets influenced the number of trips made to and from home during evacuation (54 per cent) and slowed down the speed of evacuation (43 per cent).

Those who evacuated were also asked if they contacted anyone for immediate assistance (help or information) with evacuation of their pets. More than half (58 per cent) contacted no one, 30 per cent contacted neighbours or friends, nine per cent asked for help via social media, eight per cent contacted emergency services, and the same proportion contacted local council, local veterinary clinics and online sources for help, (six per cent for each).

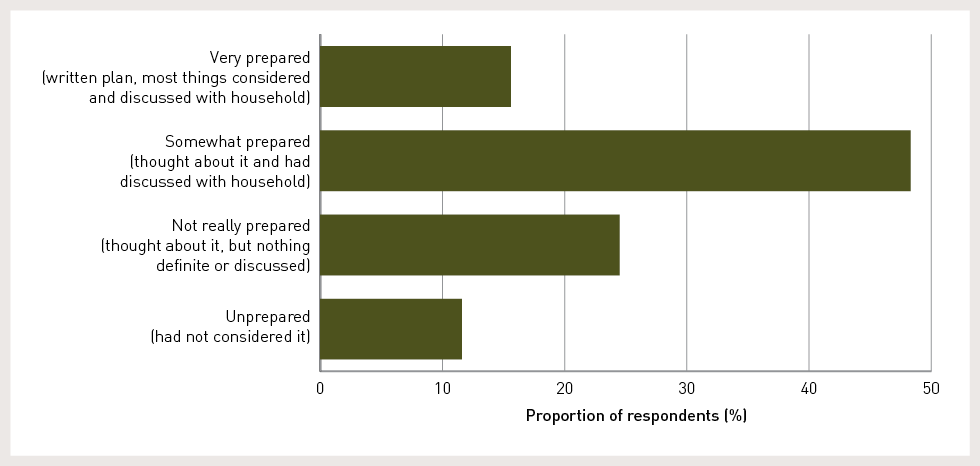

Respondents were asked to reflect and report on how prepared they felt they were prior to the disaster/emergency event. Figure 4 summarises these data.

Figure 4: Reported level of preparedness prior to the disaster/emergency.

When asked about consideration of pets in evacuation planning, high proportions of those who reported being ‘very’ or ‘somewhat’ prepared had considered all their pets (96 per cent and 87 per cent respectively). Similarly, most owners planned to keep ‘all’ their pets with them when they evacuated (74 per cent), a further 21 per cent planned to keep some with them and take others to a different location, and only one per cent did not plan to take their pets.

This study provided details of pet owner experiences during Australian emergency events; their preparedness, and their actions. It is clear that household pet composition is often complex, with the majority owning multiple animals of multiple types. In a disaster or emergency situation this translates to complex evacuation scenarios, with different pets with different needs; practical considerations, transportation, and destinations. With a third of the sample reporting they were unprepared before the disaster, this emphasises the need for higher levels of preparedness, planning, and discussion.

The experiences reported in this study suggest that certain hazards are more likely to result in different challenges for pet owners. Time to evacuate is likely to be shorter for bushfires and local emergencies, requiring unimpeded execution of evacuation plans, whereas time away from home is likely to be longer in the context of flood, meaning that the probability of leaving pets at home with food for a few days is less likely to be an acceptable strategy.

Clearly all disasters are different and official advice should still remain as ‘be prepared, act early, be considerate and act safe’ (Australian Government 2014). However, the reality is that animals do get left behind. In this study approximately 15 per cent of the sample left some animals at home either because they were deliberately left in the home or they were released to escape, or they could not be caught. Perhaps more concerning is that comments indicate some households only partially evacuated so that they could leave someone behind to take care of the animals whilst the rest of the household evacuated.

The influence of pets on decision-making and the process of evacuation cannot be underestimated. Data from this study indicates that for the vast majority of pet owners their pets influence where they go and their decision to evacuate. In addition, pets may determine the mode of transport they use, the time it takes to leave, the number of trips that are needed, and increases the overall stress of evacuation. Even with these encumbrances pet owners will still take risks to take, or go back and get, their animals. The consequences of not taking such action are too unbearable to contemplate for many.

Finally, the importance of family and friends to help support evacuees with pets is highlighted in this study. No doubt this is an important resource for all those who need to leave their homes in an emergency. However, pet-friendly destinations are a necessity for pet owners. Most people plan to take their pets if they evacuate and do take their pets with them. If options are not available to accommodate pets then owners will either sleep in cars or other makeshift places, or will simply decide not to evacuate.

A Newcastle firefighter reunites owner and his pet. Understandably, emotional attachments influence the decision-making and evacuation actions of people.

This study provides useful Australian data to inform those involved in the management of animals and their owners in disasters and emergencies. The sample size is sufficiently large to provide confidence in the data across a range of different hazards and provide insights into pet owner levels of preparedness for their pets, the rationale for their decision-making, and their priorities and considerations for evacuation and relocation. However, the study also has limitations. The sampling strategy for the study was uncontrolled and self-selected, which can result in biases and cannot be considered representative of all pet owners. Clearly many respondents were extremely attached to, and passionate about, their pets; ‘animal lovers’ more than simply ‘animal owners’. However, from an emergency management perspective such people are important, as these are the people most motivated to protect their pets and potentially the most likely to take risks to evacuate with them and return for them. It is also clear that most pet owners consider their pets as part of the family (Glassey 2010a) and data in this study does not differ significantly to suggest this sample is more biased in this regard. Pet ownership is, in most part, an optional undertaking. Therefore it should be expected that the majority of pet owners will feel committed and attached to their animals.

This study has provided a snapshot of Australian pet owners and their behaviours in, and preparedness for, emergencies. The findings of the study should inform planning by emergency management agencies and other stakeholders, on the behaviours and expectations of pet owners, on animal management needs in evacuation centre planning, and on future community engagement campaigns.

Animal Health Alliance 2013, Pet ownership in Australia 2013 Summary. Canberra. At: http://petsinaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Pet-Ownership-in-Australia-2013-Summary-ONLINE-VER.pdf.

Australian Government 2014, Attorney-General’s Department, Australian Emergency Management Institute. Pets in Emergencies Action Guide. At: www.em.gov.au/Documents/Action_Guide_Pets.pdf.

Brackenridge S, Zottarelli LK, Rider E & Carlsen-Landy B 2012, Dimensions of the human-animal bond and evacuation decisions among pet owners during Hurricane Ike. Anthrozoos, vol 25(2), pp. 229-38.

Blazina C, Boyraz G & Shen-Miller D 2011, The Psychology of the Human-Animal Bond: A Resource for Clinicians and Researchers. Springer, New York, NY.

Fritz Institute 2006, Hurricane Katrina: perceptions of the affected. San Francisco, CA. At: www.fritzinstitute.org/PDFs/findings/HurricaneKatrina_Perceptions.pdf.

Glassey S 2010a, Pet owner emergency preparedness and perceptions survey report: Taranaki and Wellington Regions. Wellington: Mercalli Disaster Management Consulting.

Glassey S 2010b, Recommendations to enhance companion animal emergency management in New Zealand. Wellington: Mercalli Disaster Management Consulting. At: http://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/glassey%20-%20report-recommendations%20to%20enhance%20companion%20animal%20em%20in%20nz.pdf.

Heath SE, Voeks SK & Glickman LT 2000, A study of pet rescue in two disasters. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, vol. 18(3), pp. 361-81.

Heath SE, Voeks SK & Glickman LT 2001, Epidemiologic features of pet evacuation failure in a rapid-onset disaster. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 218, pp. 1898–1904.

Hunt M, Al-Awadi H & Johnson M 2008, Psychological sequelae of pet loss following Hurricane Katrina. Anthrozoos, 21(2), pp. 109–121.

Irvine L 2009, Filling the ark: animal welfare in disasters. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Shiley M 2006, Dark Water Rising: Survival stories of Hurricane Katrina Animal Rescues. Shidog Films, US.

Thompson K 2013, Save me, save my dog: Increasing natural disaster preparedness and survival by addressing human-animal relationships. Australian Journal of Communication, 40(1), pp. 123–136.

White S 2012, Companion Animals, Natural Disasters and the Law: An Australian Perspective. Animals, vol. 2(3), p. 380.

Zottarelli LK 2010, Broken Bond: An Exploration of Human Factors Associated with Companion Animal Loss During Hurricane Katrina. Sociology Forum, vol. 25(1), pp. 110-22.

Dr Melanie Taylor is an occupational psychologist working in risk perception and risk-related behaviour, with a focus on disasters and mass events of significance to national security, such as terrorism, pandemic, and emergency animal diseases.

Dr Penelope Burns is a general practitioner and a researcher working in disaster medicine with a particular interest in physical and mental health in the recovery.

Greg Eustace is an expert in emergency management and the psychosocial impacts of disasters with experience in animal management in emergencies.

Erin Lynch was a final year science student employed on a UWS scholarship to work on this project. Erin has experience of animal evacuation in cyclone shelters in the Cayman Islands and she is a WIRES volunteer.

Melanie, Penelope and Greg are currently involved in a Bushfire and Natural Hazards Cooperative Research Centre project ‘Managing Animals in Disasters: Improving preparedness, response, and resilience through individual and organisational collaboration’.