The Sydney World Youth Day Catholic Festival in July 2008 event attracted 223,000 registered pilgrims, including 113,000 domestic attendees and 110,000 international visitors from 170 nations; making WYD08 the largest event ever hosted in Australia.1,2 An estimated 400,000 people attended the final mass, and over 500,000 viewed the Papal “boat-a-cade” and motorcade held in central Sydney.2 Pilgrims were accommodated in a variety of settings including homestay, school and church halls and gymnasiums and at Sydney Olympic Park.

Important variables affecting medical presentations at mass gatherings include weather, event type, age, crowd mood and density, and event duration.3 While there is now comprehensive information regarding medical and public health management of WYD events and other religious mass gatherings,4-7 there remains a paucity of documented information regarding mental health needs and response requirements for such events. Given that an estimated one million pilgrims attended the recent World Youth Day 2011 in Madrid, an event marked by heatwave conditions8 this continues to represent an important gap in our event preparedness knowledge.

The aim of this paper is to assist future preparedness by 1) detailing the mental health planning and response elements of a World Youth Day event; WYD08 and 2) examining indicative data of mental health presentations and their management during such an event.

Papal “boat-a-cade”. Water transport formed part of the Pope’s journey to the final mass.

Senior NSW Health mental health officers worked with health and emergency service personnel in the eighteen months leading up to World Youth Day and joined the WYD08 Health Steering Committee, convened by the State Health Services Functional Area Coordinator (HSFAC).

A background literature search was conducted regarding mental health needs relating to religious mass gatherings, and related health needs and preparedness. There is evidence that higher temperatures and major changes in temperature are associated with increases in range of medical presentations.3 This can be heightened when there is lack of access to water or people deliberately restrict fluid intake due to a lack of toileting facilities or for other reasons.9,10 However, little specific information could be found regarding mental health needs and service presentations in these contexts. Useful information was gathered through communication with senior public health officials involved in the planning for WYD02 in Toronto. The experience in Toronto indicated that significant impacts on mental health services may be associated with this event. These are thought to have resulted, in part, from hot weather conditions, large crowds, pressure on available facilities (toilets, rubbish collection etc.) and the nature of the event itself, which resulted in some attendees feeling overwhelmed. (Dr Bonnie Henry, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control).

Heat related illness did not feature in Sydney because WYD08 occurred during winter. Cold conditions were anticipated for the estimated 300,000 pilgrims who would take part in the overnight vigil (’sleepout’) prior to the final mass and significant preparation was undertaken for this. The long distances people would need to travel to Australia, notably from Europe and North America and the limited social support that might be available, were considered to be potential risk factors. However, it is also possible that those most vulnerable to mental health problems were less likely to attend due to such factors.

At the individual level, specific concerns were raised regarding potential presentations of so-called ‘Jerusalem syndrome’, a spectrum of conditions characterised by the development or exacerbation of religious delusions in vulnerable individuals during such events. Such conditions were first documented and treated in Jerusalem in the early 1980’s and most commonly affect out-of-region individuals on religious pilgrimages.11

Concerns were also raised regarding the potential emergence of crowd anxiety phenomena or ‘epidemic hysteria’. Typically, such episodes are triggered within groups by sudden exposure to an anxiety-causing agent, such as an innocuous gas or food-poisoning rumours. Terrorism-related themes have also increased since the September 11 attacks, including fears associated with chemical and biological agents. 12 While there are no known associations with religious festivals per se, there is some evidence that younger people may be more susceptible to such phenomena.13 To address this, a section on mass hysteria was prepared for the WYD08 Health Risk Assessment and information prepared for field workers. This reinforced the need for; surveillance/intelligence gathering about possible misinformation or perceptions regarding ‘ambiguous’ events; crowd control systems and procedures, and clear and frequently updated information and reassurance from authority figures, to address concerns early and forestall any outbreak of anxiety or panic.

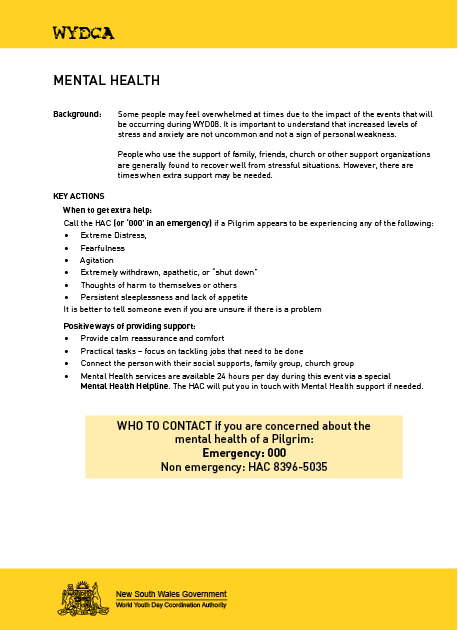

Figure 1. Mental health information for accommodation supervisors.

Mental Health planning was well integrated with the rest of the Health and Emergency Response system. Mental Health services at state and Area levels worked closely with other major stakeholders, including close liaison with the then Department of Community Services, which has responsibility for coordinating welfare and personal support services in a disaster.

At service level, Area Mental Health Directors planned for an increase in demand on services and the impact of road closures and major events on staff and service provision. Risk management plans were developed that focussed on issues of clinical care, patient safety and management, and the health workforce. In the weeks leading up to and during the event regular teleconferences were convened with mental health directors across NSW to share information and discuss concerns.

Pilgrim accommodation at Sydney Olympic Park.

Health and safety tips were included in electronic newsletters that were sent to registered pilgrims in the weeks prior to their arrival. This included advice to bring regular medications and prescriptions and, where indicated, a letter from a treating health professional. Health information packs were also developed for supervisors of accommodation sites (see Figure 1). These included a mental health section containing advice on what to expect and suggestions for providing support and assistance, and information about the ambulance Health Access Coordination (HAC) telephone service which was expanded to provide health advice tailored to group leaders and supervisors.

In addition the Disaster Mental Health Helpline was activated for use as a mental health triage and referral system. Staff from the HAC service could put callers in touch with the Mental Health Helpline if required. The HAC line processed 325 calls during WYD08 which greatly assisted early identification of health problems.

As part of event preparedness, an operational assumption was that mental health presentations during WYD08 would include acute stress reactions, somatic complaints, post traumatic symptoms, first-onset psychosis and other conditions with psychotic features and/or exacerbations of pre-existing conditions

Information was prepared to assist medical staff at On-site Medical Units (OMUs) to assess, manage and refer people presenting with mental health problems such as these. This information was developed to be compatible with existing medical protocols and included mental health management principles (see Figure 2). For more serious presentations, clear pathways to inpatient or Emergency Department care were identified, along with the option of emergency mental health care at specialist mental health facilities.

Figure 2. Mental health management principles for medical staff

The NSW Health disaster arrangements are set out in NSW HEALTHPLAN (v3.5 December 2009), a supporting plan to the State Disaster Plan (DISPLAN). NSW Healthplan incorporates the five major contributing health service components; Ambulance, Medical services, Public Health, Mental Health and Health information. For each of these components, a controller is designated, reporting to the State Health Services Functional Area Coordinator (State HSFAC). The Mental Health Controller works closely with other elements of the health response and in close collaboration with relevant government and community response agencies.

In the event of a disaster, under NSW HEALTHPLAN, the State Mental Health Controller is responsible for coordinating the mental health resources that are needed in response to the event as well as ensuring that core mental health services are maintained. During WYD08, the status of NSW HEALTHPLAN was elevated to Standby, in anticipation of impacts across the whole health and emergency system. The Health Services Disaster Control Centre was established, which coordinated the whole-of-health response and liaised with event organisers and other emergency response agencies.

The primary reporting mechanism involved twice daily reports from Area Directors of Mental Health (Area Mental Health Controllers under HEALTHPLAN) to the Mental Health Controller and the Area HSFAC. These were forwarded to the HSDCC and incorporated into twice daily situation reports which detailed the wider health response.

The Area Mental Health Services ran on a ‘business as usual’ basis with contingency plans in place should there be a significant increase in community demand.

At event sites mental health consultation was available to OMU staff via a single telephone line directed to a mental health clinician. If the decision was made that a patient required further assessment/treatment, ambulance transport to an appropriate Emergency Department could then be arranged. Medical officers at OMU’s could also refer non urgent cases to community follow-up.

In the event of a critical incident or an increase in mental health presentations the Mental Health Controller could be contacted to arrange for mental health staff to rapidly attend and work alongside physical health staff at OMU’s. Mental health staff were available on standby for such contingencies.

The 24 hour NSW Mental Health Helpline was activated for WYD08 with the number given to the HAC and other responding agencies for assistance with mental health issues as required. This 1800 number is established for use during large scale special events and in response to major incidents or disasters. Mental health professionals briefed for the event provided psychological first aid, risk assessments and referral to mental health services as required.

WYD08 mental health triage/assessment forms were stored in each OMU for documentation of mental health presentations and inclusion in patient medical record files. These forms were designed for the brief recording of presenting problems, relevant history, relevant support and contacts, risk assessment and arrangements for follow up.

The NSW Mental Health Controller participated in daily teleconferences convened by the State HSFAC during WYD08 and was responsible for coordinating the provision of mental health staff to assist at OMUs and advice regarding crowd management issues.

According to data collected by the NSW Health Emergency Management Unit during the event, On-Site Medical Units at major events treated 465 Pilgrims. Approximately 80% of presentations were treated and discharged with 11% requiring transfer to hospital.6 In addition, there were 508 Pilgrim presentations to Emergency Departments with 84 admissions during the period when major events were occurring.14 An overnight clinic at Sydney Olympic Park, where 14,000 Pilgrims were accommodated, treated 79 Pilgrims. Two influenza clinics established at this site treated a total of 419 people.14 Plans were in place to manage expected outbreaks of infectious disease and hypothermia. Re-warming centres were established and pre-event advice given to pilgrims to prepare for winter conditions.4

Figure 3. Primary medical presentations during WYD08.

Mental health presentation and response data relating to WYD attendees was captured prospectively and collated daily through Emergency Departments and OMUs in field locations via daily situation reports.

Twenty mental health presentations were reported during WYD08 via these sources (see Table 1).15 Eleven pilgrims presented to EDs resulting in seven admissions. Nine presented to OMUs with a range of mental health problems, six of which were anxiety related and three with psychotic features. Assessments indicated that all of the OMU presentations involved individuals who had a pre-existing mental health condition. Whilst a small number overall, this does indicate that pre-existing conditions are a risk factor for event-related presentations.

Preparation of an On-site Medical Unit.

Table 1. Mental Health presentations and dispositions of WYD08 participants.

|

Type |

Dispositions |

Number/Rate |

|---|---|---|

|

ED Dispositions: |

Hospital admission |

7 |

|

Referred Community Mental Health (CMH) and GP |

1 |

|

|

Discharge to self-care and supported accommodation |

3 |

|

|

Emergency Department: total presentations |

11 |

|

|

OMU Dispositions: |

Transfer to tertiary hospital |

1 |

|

Referral to G.P. |

4 |

|

|

Referral to CMH and G.P. |

1 |

|

|

Assessed / left before follow-up completed |

2 |

|

|

Self directed to supported accommodation |

1 |

|

|

Onsite Medical Units: total presentations |

9 |

|

|

ED/OMU Medical Utilisation |

Rate: (registered pilgrims) |

223,000 |

|

Mental Health |

MUR= 0.9 / 10,000 attendees |

|

|

Primary Medical |

In comparative terms, there was a relatively low rate of presenting mental health problems. The medical utilisation rate (MUR) of WYD08 mental health presentations was substantially lower than that of primary medical presentations; at a ratio of approximately 47:1 (see Table 1).

Cool but temperate weather; long distances from major source countries; positive crowd mood and highly organised support and accommodation sites were probably all factors contributing to the relatively low number of mental health presentations observed during WYD08. Similarly, the extremely low rate of drug and alcohol related presentation was also a likely ‘protective’ factor regarding this outcome.4 Overall, this outcome was in keeping with findings from other religious mass gatherings in other countries.3 The purpose and demographic features of WYD08 mean that extrapolation of its findings to other events must be done with some caution. There is also considerable variation within WYD events themselves, notably in total crowd numbers and weather conditions.5,8 However despite these limitations, the current findings provide a useful reference point for the planning of similar events.

Experience has shown that key components of a successful mental health response include i) its comprehensive alignment within the health response, ii) planning to support the continuation of core business throughout the event and iii) working closely with welfare and recovery agencies, and service networks at local levels. Consistent representation at community and interagency meetings helps to allay anxiety about potential mental health impacts and strengthens relationships of trust and lines of communication. Much of this work occurs during ‘peace time’ i.e. as part of an ongoing service planning and event preparation.

Clear, consistent and frequent communication across NSW mental health services and with key elements of the health response were a critical element of the mental health response during WYD08. The specific reporting lines and feedback structures were effective and generally operated as expected. Overall, the inclusion of mental health in health and emergency planning meetings from 18 months prior to WYD08 strengthened its ongoing role in strategic planning for disasters and major events.

Specific initiatives will require further refinement for events of this kind. The Mental Health Helpline and telephone consultancy received very few contacts during WYD08. This may have been due to the specific nature of the event, its high level of background support and possibly the effectiveness of the general health line (HAC) in fielding and directing those with health issues at an early stage. Despite low usage, the Helpline provides an identifiable and centralised point for mental health assessment and referral and should be considered for future events. Similarly, the Mental Health Triage/Assessment form for use at OMUs were underutilised and may require further incorporation with physical data at future events.

WYD08 resulted in very little impact on mental health services with a relatively small number of presentations and no disruption to the overall health system. Importantly, this event provided a good opportunity to assess mental health needs and strengthen operational partnerships with Health and emergency response agencies, in readiness for future major events.

The authors wish to thank the Director and staff of the New South Wales Health Emergency Management Unit.

1.WYD 2008. History of WYD. Viewed 2 July 2011. <http://www.wyd2008.org/index.php/en/about_wyd08/history>

2. WYD 2008. Final statistics. Viewed 2 July 2011. <http://www.wyd2008.org/index.php/en/about_wyd08/final_statistics>

3. Milsten, A.M., Maguire, B.J., Bissell, R.A., & Seaman, K.G. 2002, Mass-gathering medical care: a review of the literature. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, Vol. 17, No.3, pp 151-162.

4. Smith, M.W.H., Fulde, G.W.O., & Hendry, P.M., 2008, World Youth Day 2008: did it stress Sydney Hospitals? Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 189, No.11/12, pp. 630-632.

5. Fizzell J., & Armstrong P.K., 2008, Blessings in disguise: public health emergency preparedness for World Youth Day. Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 189, No.11/12, pp. 633-636.

6. Tyner, S. Analysis of presentations to onsite medical units during World Youth Day 2008. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, (In press).

7. Bassil, K.L., Henry, B., Rea, E., et al. 2005, Public health surveillance for World Youth Day. Toronto, Canada, 2002. Morbidity & Mortal Weekly Report, Vol. 54(Suppl), 183.

8. Associated Press. Storm cuts short pope's speech in Spain. guardian.co.uk, Sunday 21 August 2011. Viewed 1 September 2011. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/aug/21/storm-pope-speech-spain-madrid>

9. Schulte, D., & Meade, D.M., 1993, The Papal chase. The Pope’s visit: A "mass” gathering. Emergency Medical Services, Vol. 22, No. 11, pp.46–49,65-75,79.

10. Federman, J.H. & Giordano, L.M., 1997, How to cope with a visit from the Pope. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 86–91.

11. Bar-El, Y., Durst, R,, Katz, G., et al, 2000, The Jerusalem syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 176, pp. 86-90.

12. Bartholomew, R.E., & Wessely, S., 2002, Protean nature of mass sociogenic illness (from possessed nuns to chemical and biological terrorism fears). British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol.180, pp. 300–6.

13. Balaratnasingam, S., & Janca, A., 2006, Mass hysteria revisited. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, Vol. 19, No.171-174.

14. Post WYD08 operational debriefing, New South Wales Health Emergency Management Unit, 11 August, 2008.

15. Operation WYD08, Ambulance Service of New South Wales Situation Reports, 15-20 July, 2008

Katrina Hasleton is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Mental Health and Drug and Alcohol Office, New South Wales Department of Health where she Co-Chairs the Mental Health Disaster Advisory Group.

Garry Stevens is a Senior Research Fellow at the Disaster Response and Resilience Research Group, School of Medicine, University of Western Sydney.

Penelope Burns is the current General Practice Fellow in Disaster Medicine at the Disaster Response and Resilience Research Group, School of Medicine, University of Western Sydney.

Correspondence: Garry Stevens may be contacted at g.stevens@uws.edu.au.