As he looked over the devastated town of Grantham for the first time, Lockyer Valley Mayor Steve Jones was horrified. Then he began thinking about the future.

“If you’re ever going to make a change,” he thought, “now’s the time to do it”.

The torrent on January 10 killed at least 22 people in the Lockyer Valley, and Grantham was among the communities that bore the brunt.

Cr Jones wasn’t in Grantham when the flood came, he arrived that evening. Within about 24 hours, he’d set his mind on a plan.

His idea was as simple as it was radical: to move the town to higher ground to prevent the place becoming a ghost town, and attract new residents. His fellow councillors unanimously backed it, and it quickly won the support of the Queensland Government.

The idea hasn’t grabbed everyone in the community, but enough households have registered their interest that work has already started on shifting them uphill in a unique land swap arrangement.

The council bought 935 acres of grazing land overlooking the area, then subdivided it to reflect the sizes of existing blocks down below. It will swap one new block for one old block.

This is where the State Government was able to help—it knocked down years of planning hurdles to get the project moving now.

The council will try to sell the lower lying land to farmers, or put it to a community use.

Cr Jones says the idea is not so much about preparing for another similar event—because that seems extremely unlikely—but ensuring the community emerges stronger from the floods.

“The immediate things that flashed up in my mind were: people are not going to get finance to rebuild, because what financial institution will finance a loan to build in a place where this has happened? And secondly they’re going to have trouble getting flood insurance in the future,” he says.

“It was really important, I thought, that we start to consider options before we start the rebuild."

“I talked to my own council first, and my own council were very supportive of the idea—it’s very much out of the square, it’s a big project to start talking about these sorts of things.”

He says there were several principles he outlined from the start, and is determined to stick to. Foremost of those is that for the scheme to work, it must be voluntary.

“If you try to do things with compulsion, they won’t get community support and they won’t work,” Cr Jones says.

“And, the idea of the land swap in my mind was quite clearly: we would offer people a better piece of land that’s worth more money and gives them more collateral. It’s a safe block of land, they can lie in bed at night when it rains and not be worried. But, more importantly, I think, it preserves the nature of the town.

“Most towns where there’s serious natural disasters often become ghost towns, everyone leaves. We didn’t want that to happen. It’s really important that people stay and it’s really important that the (population) numbers grow,” Cr Jones says.

“We realised right from day one it’s going to cost a huge amount of money, they (councillors) were not daunted by that, they backed me 100 per cent on that.”

Stage one is expected to cost the council $25 million, and includes the undisclosed cost of purchasing the land from a local farming family. The council will use its own reserves and is considering also borrowing some money if it can get a concessional rate.

“We’re happy to put that money out. We want to get those people up there safely and all settled down and under control. As we move along, we want to develop further land and we’ll sell some of those blocks off to bring new families in,” Cr Jones says.

“If we could get another 100 families to come and live in Grantham in a really nice estate, with nice sporting facilities, it’d really lift the whole profile of Grantham and people would love the place they’re living in. This estate’s on top of a ridge, it looks out over all the farming land, it really is a nice outlook.”

Residents who take up the offer will need to find their own way to pay for their new house to be built, either through insurance, donation or their own funds.

“We know that the maximum we could handle in stage one is about 80 lots because a lot of them are still waiting on insurance,” Cr Jones says.

“Until they get the answers from their insurers they don’t know what their circumstances are. Insurance companies may tell them they’ll only pay if they rebuild on that site. There are about 80 possibilities in the first round and we’ve got 60 of those signed up already.”

The council involved the community in its plan early on, and hired a consultant from Brisbane to help with that process.

“We held three or four community meetings and we said ‘ok, this is what we’d like to do, we’re prepared to do it, we need your vision on how you’d like this to happen and what you’d like – size of blocks and that sort of thing,” Cr Jones says.

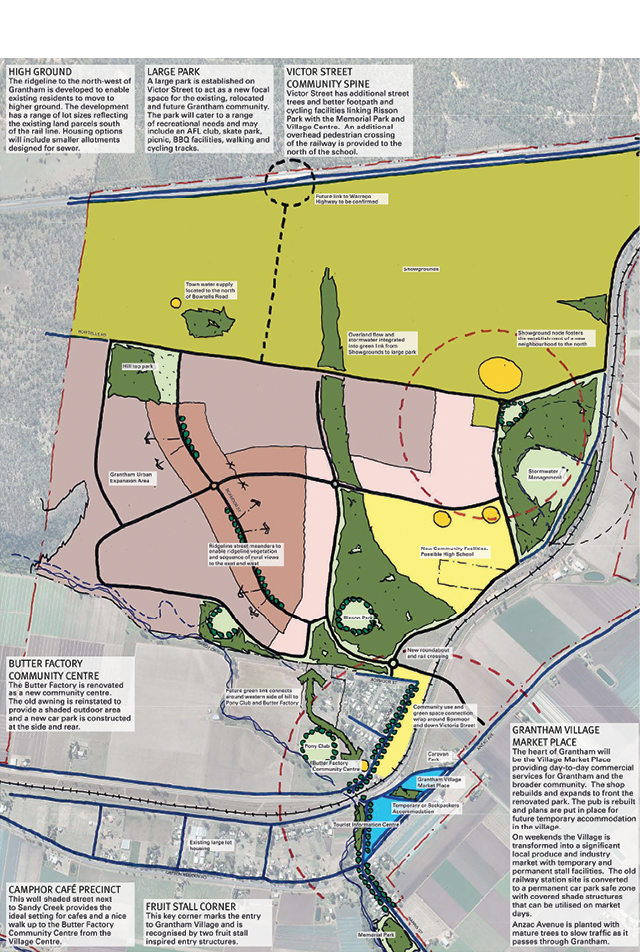

Mayor Steve Jones, in front of community information about the Lockyer Valley land swap.

“So the community itself actually had about a 90 per cent input into what we’re doing. It was just the idea we put up, and they put the meat on the bones.”

About 120 families in the area are eligible for the deal. Cr Jones says one of the reasons he is so passionate about the project is he feels Australian communities sometimes fail to learn enough from their natural disasters – and often rebuild in the same spot.

“We go on with millions of dollars in inquiries and most times we’re no better off than when we started. This is a case where you put money in and at least the people are safe, they can get insurance (for the new property) and they can get on with their lives.”

He expects there will be some who choose to stay where they are, and for legitimate reason.

“We’re not trying to force them. You might have someone who’s got a very good quality brick house on a slab that’s on the periphery of the damaged area. It might have only $100,000 damage.

“The fact it wasn’t severely damaged this time means it probably won’t be next time – so those people will remain.

But I think over a long period, you’ll find a lot of people will move up there.”

At the time of writing the council was continuing to hold public meetings on the scheme every Wednesday night.

Beyond Grantham, councils in every state and territory of Australia are grappling with the aftermath of the extraordinary spate of natural disasters the country has had in recent months. As the closest level of government to the people, they must now repair their communities.

Genia McCaffery, the president of the Australian Local Government Association, says there is much to be proud of in recent events, and—as in any disaster—much to be learned.

Strong local leadership has steered communities well, she says, and this can only be possible with a great deal of trust.

“Leadership isn’t about just responding to a particular incident. What leadership is about is having a long established track record with your community, so when you’re there saying ‘this is what you should do’ people recognise you, they know you and they have trust in you,” she says.

“That kind of proven track record, I think, is critical. Then, being able to give people clear directions about the next steps they should take. We saw that very much with Anna Bligh, where she was constantly communicating to people about what was happening, what to prepare for, giving warnings and then guidance.”

Ms McCaffery says more and more councils are now developing disaster response plans, and most of those in vulnerable areas have them already.

“Those plans identify staff, resources and priority actions for when or if a disaster strikes. Councils are also using more social mapping to better understand their communities,” she says.

“To me the first step of your disaster management plan is getting a good understanding of your community, particularly its vulnerabilities and strengths, and a clear history of your community and the specific hazards it’s faced, flood or fire,” Cr McCaffery says.

“It’s understanding the make-up of your population, particularly the presence of aged or non-English speaking groups, and then understanding what the strength of community relationships is, particularly volunteer and community groups.

“That social mapping is a critical part of doing good disaster planning. There’s a lot of work being done there. I think a lot of the effective response in Queensland was because the councils had a good understanding of their community profile.”

Ms McCaffery believes the new National Strategy for Disaster Resilience, which COAG adopted in February, will be useful in further boosting resilience.

“Measures to do this include identifying priority hazards, and putting in place solid land use planning to avoid potential hazards, she says.

“Then, ensuring clear and effective communication with individuals and households within the community, and developing good continuity planning by business and government.

But local government also needs all the help it can get in preparing its communities,” she argues.

“There are a number of really good partnership programs like the Regional Flood Mitigation Program, the Bushfire Mitigation Program and the Natural Disaster Mitigation Program—all of these recognise that councils don’t have the resources to tackle them alone. That it makes good sense, in every sense, economic, social and environmental to spend significant amounts of money on mitigating prior, rather than spending huge amounts of money later,” Ms McCaffery says.

“For every $1 you spend on good mitigation work, it’s saving $2 on post recovery expenditure,” she says.

The Queensland Government has estimated the damage bill from the floods and Cyclone Yasi at $6.8 billion. Some of that will be met under the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements, in which the Commonwealth funds up to 75 per cent of eligible costs.

“There is a recognition across the country that local government does not have the financial resources to do this work on its own, but it’s probably the most effective level of government to deliver this infrastructure – so this is an area where we really do need to be adequately funded by the federal government, to put these mitigation works in place,” Ms McCaffery says.

“I think one of the things we certainly saw in Queensland was the value of effective mitigation and education. Significant damage was avoided in many Queensland towns because they had spent the money to build flood levees to protect those towns.

Grantham reconstruction 2011

“Over the years, many councils have been frustrated by the planning process, when the controls they try to implement are challenged in court by developers, or overruled by state governments,” Ms McCaffery says.

“All levels of government must recognise the need for good land use planning and cooperate to stick to a set of agreed rules. This would minimise the damage caused by natural disasters.

“There are also others who must bear a large share of responsibility for disaster planning—the general public,” she says.

Construction work on land swap land.

“We’re talking a lot about what government can do, but I think one of the things we need to be pushing really strongly is that to actually help communities understand the risk and the limits of what government can actually do and the importance of people taking responsibility to prepare for disasters by having their own plan, by preparing their own property,” Ms McCaffery says.

“This is critical obviously in bushfire areas. Communities should also be encouraged to have insurance where appropriate and where available.

“It’s not just about the government fixing things, it’s about individuals being better placed to deal with what we recognise is going to be an increased incidence of these kinds of occurrences,” she says.

Cr Jones says the small town of Withcott, in the Lockyer Valley is a good example of this kind of resilience. It was damaged by floods, but no lives were lost.

“When this hit our shire, 20 out of our 23 communities were almost devastated. And it’s impossible for a council the size of ours (350 staff) to help everybody,” Cr Jones says.

“In Withcott, despite the fact the devastation was huge, and the service stations were knocked down, we didn’t have to have a single works crew go to Withcott for seven weeks – the community just did everything. They’re that sort of place, they don’t muck around,” he says.

Cr Jones said it was important for councils to harness those feelings in a community and trust people to lead their own response.

The people of the tiny town of Strathewen, north-east of Melbourne, suffered immeasurably in the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009, but if any number can help describe their loss it’s this: 27 people died, in a town of 300.

Those who remained felt abandoned by authorities, says Malcolm Hackett, a retired school principal who continues to live in his converted dairy shed because his house was destroyed.

“Rather than be defeated, the people of Strathewen mustered themselves into an incorporated legal entity, so they could attract and manage their own donated funds, and take charge of their own recovery—this attitude of the town is historic”, Mr Hackett says.

“There are a few reasons people come out here. I think one of them is to be a little bit isolated, a bit more independent and further from the forces of control,” Mr Hackett says.

“I think it’s a trait of the area. The local school was built 100 years ago by locals… the local hall was community owned and built, and in fact it still is.

“Sometimes that attitude can breed a sense of negativity—that no one cares about Strathewen.

“But it’s probably more true to say it’s people here saying ‘oh well, we’d better organise ourselves’ that’s what they’ve always done before,” he says.

The Strathewen Community Renewal Association is made up of people who’ve lived in the town all their lives, and others who’ve moved there more recently, with particular skills. There’s a lawyer, people heavily involved with the community, a company secretary, someone with a lot of experience in local government—and Mr Hackett, who is among those who understand the sometimes-glacial pace of bureaucracy, and how to speed things up.

If Strathewen felt abandoned during the fires, it is perhaps with good reason. The Victorian Bushfire Royal Commission found that although a warning had been drafted for the town that afternoon, the CFA never released it.

“There was a sense that Strathewen had been ignored,” Mr Hackett said.

In the aftermath, authorities seemed more focused on other towns, especially Kinglake and Marysville – and they received a lot of media coverage, he said.

“There was a growing sense of people saying ‘not only did they not know about us, they don’t care about us now’.

“There was a sense that we needed to correct this imbalance. Those of us who knew government well, and how bureaucracies work – and there was a sense that everyone was rushing around trying to help, but that we’d just get swept aside or rolled over by all this good will and decision making coming from other places,” he says.

Within a few weeks, a group formed.

“The idea of an incorporated association, something with legal standing, just came almost automatically. We knew that in some places there were advisory groups, but we wanted more than that. We wanted to be able to say that the group represented Strathewen, that it was a legitimate voice,” Mr Hackett says.

It also took control of funds being donated to Strathewen.

“Not being afraid of government and knowing how it operates, I think has made a huge difference to us. We’ve been able to manage lots of those anger issues that arise in lots of places because we’ve been able to say to people, ‘it’s all right, we’ll try it this way, or go that way – there are lots of ways to skin a cat’,” he says.

The association has since won the Volunteer category, in the Australian Safer Communities Awards, sponsored by the commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department.

Mr Hackett said part of the association has also helped to bridge a gulf between residents and the local council, Nillumbik. They have also produced documents advising communities and government.

Cr Jones says his community has drawn support from some of the bushfire-affected towns in Victoria.

“They’ve been very good, they’ve been very supportive, they’ve come and spoken to us,” Mr Hackett says.

“I’m actually going to make time to go down to Victoria and have a look at their circumstances – where they are two years later. And I’m certainly going to talk to them about what we have done.

“What we’ve done here is something really new, it’s outside the square and probably pretty game but I would really like this model to be looked at right across Australia when large scale disasters happen because I think within in two or three years we’ll find our community will be so much stronger, so much more advanced than if we hadn’t done it,” Mr Hackett says.

Cr Jones is confident his plan will work. “I’m 100 per cent, mate. I have been from day one. I think with these things you’ve just got to make them work and it’s going twice as good as I thought it would,” he says.