That bushfires can exceed the capacity of fire-fighting resources makes facilitating household and community bushfire preparedness a crucial risk management goal. This goal cannot be accomplished simply by making information available to people (e.g., Martin, Bender, & Raish, 2007; Johnston et al., 2005; Lindell & Whitney, 2000; Paton, Bürgelt & Prior, 2008). Sustained hazard preparation is a function of how people interpret information in social and community contexts. This view was echoed by the 2009 Victorian Bushfire Royal Commission (henceforth Commission: VBRC, 2010) where evidence presented (p. 354) suggest that involvement in bushfire preparedness groups such as ‘Community Fireguard’1 makes a significant contribution to people’s safety. Being actively involved with other community members and exchanging information and stories about bushfires are important precursors of the development of people’s risk beliefs and the enactment of these beliefs in ways that facilitate community bushfire safety (e.g., Frandsen, 2010; Kneeshaw, Vaske, Bright, & Absher, 2004; McGee & Russell, 2003; Paton et al., 2008; Vogt, Winter, & Fried, 2005; Winter, Vogt, & McCaffrey, 2004). The Commission’s recommendation went further and argued for bushfire preparedness to be seen as a ‘shared responsibility’ between communities, fire agencies, and governments (VBRC, p. 352). If the benefits of this goal are to be realised, it is first necessary to identify how the relationship between community and agency can be developed in ways that promote bushfire safety as a shared responsibility. Consequently, research into how communities and agencies can be engaged in reciprocal and complementary ways is required (Kumagai, Bliss, Daniels, & Carroll, 2004; McCaffrey, 2007; McGee & Russell, 2003; Paton & Wright, 2008; Winter, Vogt, & McCaffrey, 2004). One approach to achieving this is the subject of this paper.

As a means of complementing the effective (Enterprise Marketing and Research Services, 2010) three-year Bushfire: Prepare to Survive awareness campaign, the Tasmanian Fire Service (TFS) introduced the Community Bushfire Preparedness Pilot (Pilot) and appointed a Community Development Officer in March 2009 to trial and evaluate this new evidence-based intervention program. The evaluation (conducted by two independent University of Tasmania researchers) employed an action research approach to enable the Community Development Officer to tailor and progressively develop the engagement process to accommodate the findings of the evaluation. This paper is a summary of that evaluation.

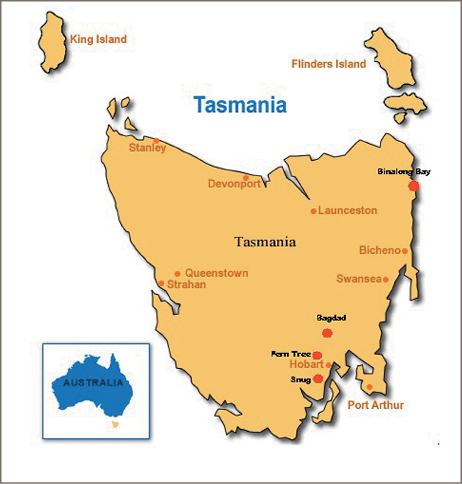

The Pilot sought to identify how to engage with communities to increase public acceptance of bushfire safety as a collective responsibility between the TFS and communities. Through consultation with TFS managers and District Officers appointed to those regions, four communities, considered to have comparable levels of bushfire risk, were chosen for the Pilot. To ensure that the sample was representative of Tasmanian communities, work was undertaken in one northern rural, one urban interface, two southern rural, and a community with a recent major bushfire experience (as well as various demographics and community characteristics). The four communities were Fern Tree, Binalong Bay, Huntingdon Tiers in Bagdad, and Snug Tiers. [see map]

Tasmania, target communities indicated by red dot.

The local volunteer fire brigades in each community were consulted to gain an insight into: existing levels of engagement with the community; their capacity for community liaison and education; awareness of their community’s preparedness, capacity and vulnerability; local knowledge of key community leaders and groups; and, to gain their support for the project. All four brigades supported the project. Whilst some brigades (e.g., Fern Tree) indicated a strong, existing culture of engagement in their community and that promoting community preparedness was integral to their voluntary operations, other brigades indicated their community involvement was limited by lack of volunteer numbers or reflected an existing cultural attitude that their role as volunteers was ‘to put the wet stuff on the hot stuff.’

Surveys collected from participating brigade members following these consultations indicated that 41 of 42 volunteers believed that encouraging two-way community-brigade engagement was beneficial to increasing bushfire preparedness and enhancing brigade ability to assist facilitating the preparedness goals of communities. Importantly, the engagement process employed in the Pilot was perceived to increase people’s understanding of the respective roles and responsibilities of volunteer fire brigades and community members, and the notion of ‘help us to help them.’ Thus, the community engagement approach provided a platform to help meet the Commission’s (2010) objective of promoting bushfire risk management as a ‘shared responsibility.’ Volunteer fire brigades who were not actively engaged with their community suggested that this was due to a lack of resources and disinterest from the community; a finding that reinforces the value of promoting active community participation in social contexts prior to implementing the Pilot in each area (Paton & Wright, 2008). Consistent with previous work (McGee & Russell, 2003), the survey data highlighted the benefits of having a community liaison officer in a brigade. The general consensus of the brigade members was that this person should have fire-fighting experience, have a strong commitment to benefiting their community, and be someone who was familiar with the area and its community members.

Through consultation with key representatives in each community (e.g., community leaders, volunteer fire brigade, local council etc) all four communities decided that an interactive information session (henceforth ‘Forum’) about bushfire preparation in their local community would be the most effective way to introduce the Pilot and provide bushfire preparedness advice to the communities’ residents. Promotion of the Forums was largely organised by the Community Development Officer although, where possible, the local volunteer fire brigade and/or other community members assisted this process. The TFS District Officers agreed to provide the expert bushfire advice at each Forum.

Binalong Bay Forum (13th September, 2009): Binalong Bay Fire Station. As well as the District Officer and Binalong Bay volunteer fire brigade attending to provide advice and fire pump demonstrations, several St Helens volunteer fire brigade members also participated, as did representatives from the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service, Forestry Tasmania, and local government. All presenters participated in the Question and Answer session at the end of the Forum. In total, 45 community members and approximately 20 volunteer fire brigade representatives attended the Forum.

Snug Tiers Forum (18th October, 2009): Snug Memorial Hall. The main presentation was given by the District Officer along with speeches given by Parks and Wildlife and a Community Fire Guard group leader from Kettering (a neighbouring township). A Question and Answer panel following the presentations also consisted of representatives from local government (a Councillor, Development Officer, Planning Officer, and Bushfire Care Officer). Seven members from the Snug and Margate volunteer fire brigades also attended and a display of fire fighting products from TasFire Equipment was provided. Approximately 45 people attended the Forum, of which 15 were representatives, presenters, or volunteer fire brigade members. The Forum was concluded with a barbeque and opportunity for informal discussion with the various representatives.

Fern Tree Forum (1st November, 2009): Fern Tree Hall. The Fern Tree volunteer fire brigade is very active in the community and approximately 120 community members attended the Forum, with opportunity to ask questions of panel members, which included TFS representatives, local government representatives, and members of local Community Fire Guard groups. After the Question and Answer session, residents were given the opportunity to see fire pump demonstrations and engage in further discussion with TFS members and other representatives over a barbeque lunch.

Fern Tree Forum, November, 2009.

Huntingdon Tiers, Bagdad Forum (15th November, 2009): Bagdad Community Club. The District Officer, General Manager of the Midlands Council, and a local police officer gave presentations, and members and young cadets of the local Bagdad volunteer fire brigade gave a demonstration of fire pumps. In total, 11 community members, 10 volunteer fire brigade members, and six other representatives attended the Forum. The Forum was concluded with a barbeque lunch prepared by the local volunteer fire brigade.

Forum Feedback. Post-forum feedback surveys were distributed to participants. Seventy seven people completed surveys (approximately 40% of those who attended Forums). The surveys assessed views on the format of the Forum itself, as well as perceptions of bushfire preparedness, benefits of attending Forums, and roles and responsibilities of residents and fire agencies. Overall, all participants agreed that the Forums were well organised, enjoyable, made them re-evaluate their own bushfire risk, and gave them a better understanding of appropriate sources of bushfire information.

When asked what they learnt from the Forum, five main themes emerged including: that bushfire management is a complex issue and that there is a lot of background work that goes on to manage it; the planning involved to prepare for bushfire; the various recommended preparedness measures; new information (e.g., Fire Danger Rating); and, actual fire behaviour. Residents indicated that they would have liked more specific information about home fire protection, information regarding the TFS (e.g., how to join), and whether there was an evacuation plan for their area or where to go if they had to leave their property. Of particular interest was the finding that 71 of 77 participating residents (92.21%) indicated that they intended to become more prepared for bushfire as a result of attending the Forum.

Furthermore, 42.86 percent of residents indicated that their perception of their own and their volunteer fire brigade’s roles and responsibilities had changed a nd that they now had a better understanding of the limited resources of volunteer fire brigades and that home owners are responsible for their own preparation. For those whose perceptions of roles and responsibilities had not changed, many explained that this was because they were already aware of these roles and responsibilities. The most commonly listed benefits of attending included: acquiring more information about bushfires and how to prepare for them; understanding that community preparedness is a community responsibility; and the motivation to start preparing immediately (which was itself stimulated by discussing bushfire issues with others). Consistent with its theoretical foundations (McGee & Russell, 2003; Paton et al., 2008; Paton & Wright, 2008) forum attendance facilitated preparedness being seen as a collaborative activity, increased the likelihood of people continuing to discuss bushfire preparedness in everyday life, identified future needs, and arguably increased the likelihood of preparedness becoming a social norm. When asked how the Forum could be improved the most common answers were: better attendance from other community members; more specific information about how to prepare their properties; evacuation procedures in their community; and, longer question time. Telephone interviews conducted with residents from these target areas (data which is the foundation of a current PhD thesis), also suggests that these Forums were an effective means of raising bushfire awareness and promoting bushfire preparedness actions. Table 1 provides examples of such sentiment from the telephone interviews conducted.

Table 1. Extracts from Telephone Interviews with Residents of the Four Target Areas and their Remarks about the Forums.

|

Residents |

Remarks |

|---|---|

|

Ruby from Bagdad (12/1/10) |

“...yes, we’ve probably done more of it [bushfire mitigation activities] this year than we have in the past...we’ve taken out a couple of trees that we’ve left in the past umm but like there’s a lovely big tree growing up against our um shed... we took that tree away, um and it’s been growing there for a long time, and it looks lovely, we were really sad when we took it down but err so we’ve made a few decisions this year, probably based on doing that Forum that we that we wouldn’t have otherwise...and there are others [trees] that we are contemplating taking out um because, that we wouldn’t have before (before the Forum?) yes...” |

|

Tony from Binalong Bay (7/1/11) |

Is there anything to gain from going to another [forum]? “Oh I think there is, yeah, yeah like I think it’s just a...good way, good reminder, but umm yeah like, it’s always in the back of your mind, especially this time of year, umm yeah but it’s always a good reminder...like we haven’t spoken for some time you know, as a family about yeah bushfire plans and you know, where the tennis balls and socks are for plugging the down pipes and all that sort of stuff but if you, you have a forum like that...it suddenly...back in the forefront of your mind and, yeah, it can probably get it, get some of those things, umm organised and discussed rather than just sort of waiting for it to happen so I think it’s a good idea, it’s like anything, you go and do training, you know, through work and yeah two years later you need to do a refresher like with First Aid or umm some other skill you’ve got yeah...” |

|

Jackie from Snug (27/10/09) |

“...and also thanks to the forum the other week, we’re working on getting everything organised, making sure we’ve got the, adequate clothing and umm, umm what do you call them, garden hoses and things readily available. So we’re conscious of all that and are working towards it.” |

|

Merv from Snug (3/11/09) |

So your little community there is quite close knit then? "Yeah, it’s it’s small, it’s not actually as close a knit, everyone’s friendly but we don’t spend a lot of time with each other, everyone knows each other so you’ll stop and have a chat on the road but we, there’s definitely potential I mean off the back of that forum the other day, there’s definitely potential for this this community to pull together and be a little bit more umm, probably planned and ready...until we went to that forum the other day, I didn’t realise or didn’t, you know, it hadn’t occurred to me that there’d been changes in their policy so yeah.“ |

|

Sandy and Gus from Fern Tree (17/11/09) |

“...(Sandy) well I mean they’re all, I mean that Forum amazed me, I’d never seen those people before! (Gus:...that meeting there the other Sunday, Sandy and I looked at each other and thought, where do these people come from...I mean we’ve been up here 30 what? (Sandy) 36 years (Gus: 36 years, and we’ve never seen 90 % of those people)...” |

The TFS Community Development Officer used the Forums to introduce the Community Development Pilot and invited residents to contact her to discuss further support opportunities. The outcome of these discussions provided the foundation for more proactive engagement between the Community Development Officer and those community members seeking to advance their bushfire knowledge and preparedness. This provided the foundation for Level 2 engagement.

Binalong Bay. Following the community Forum the Community Development Officer and District Officer met with community members (30th September, 2009) in a focus group format to discuss local and specific bushfire issues (e.g., highest risk areas, likely bushfire behaviour, specific mitigation needs). Focus group discussions were followed, at the request of residents, by three property inspections. Nine residents in total attended these property inspections and indicated their value in providing detailed, specific, and contextual information about how to prepare their homes that could not have been obtained from bushfire literature or other education formats such as the Forum. Inspections, particularly those conducted in response to community requests, are good predictors of the adoption of protective measures (Martin et al., 2007).

The District Officer endorsed the format explaining that, as well as being much more economical and less resource taxing, the community property assessments offered a larger number of residents greater access to specific and contextual information about how to prepare themselves and their homes for bushfire. The residents and the District Officer also commented on the benefit of the community members being able to discuss and share information about bushfire related matters with each other and the development of community networks. As a result of this success, the Community Development Officer organised a larger community Field Day (18th January, 2010). A bus commuted participating local residents to five properties where the District Officer provided bushfire risk assessments and advice on how to better prepare properties. Eighteen local residents participated. Interviews with participating residents (n = 5) at the completion of the Field Day indicated that they found it to be a very informative and worthwhile event. For example see Table 2.

Table 2. Participant Post-Field Day Survey Quotes Regarding their Opinion of the TFS Pilot Field Days.

|

Field Day |

Example |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|

|

Binalong Bay Field Day (18/01/10) |

Example 1 |

“[Overall impressions?] Very good, very informing. I’m a newcomer to Binalong Bay and I’m really impressed with how the firie (sic) taught us a lot of things that I knew nothing about yes. [Any improvements?] No, well I’ve got to learn all these things, but at least I’ve learned a lot more about what I’ve got to do with my property and I will join the fire brigade and err cause everyone should be helping each other...” |

|

Example 2 |

“[Overall impressions?] Very informative...I can see I’ve got work to do, and I appreciate that. I knew most of it anyway, but it just exacerbates...it’s causing me (sic) actions to be done quicker than they would normally have been done...” |

|

|

Snug Field Day (13/03/10) |

Example 1 |

“[Overall impressions?] Practical advice on fire preparation. Increased knowledge about the reality we might face. Made good connections/contact with local community. Excellent day.” |

|

Example 2 |

“[Overall impressions?] Very impressive, very good advice, facilitated community engagement and responsibility, should be continued and funded indefinitely.” |

|

|

Bagdad Field Day (30/10/10) |

Example 1 |

“[Overall impressions?] Extremely informative. I think it was valuable to be able to physically attend other properties to learn and observe what is available to fire prevent your property. It is also good to meet people in your area to maybe set up a safe area for the situations if need be.” |

|

Example 2 |

“[Improvements?] I don’t think it needs improving. If you can try and get more people and their properties on board then a larger percent of the community will learn about the danger to their houses and wether (sic) to stay and fight or evacuate.” |

Snug. In response to residents’ earlier concerns, voiced at the Forum, about excess vegetation along the narrow road verges and the process for removal of vegetation on private property, the Community Development Officer organised for Council’s hazard reduction officer to attend a Field Day (13th March, 2010). Five property owners volunteered their properties for assessment by the TFS Field Officer and 17 people attended the Field Day. The presence of the local government officer was well-received as she was able to provide detailed explanations of the hazard reduction processes and how to comply with Council’s by-laws. One of the main benefits of the event was the networking between neighbours. This resulted in a follow-up request from seven property owners from one of the most at-risk roads to establish a bushfire ‘telephone tree’. Ten Field Day participants provided feedback. See Table 2 for example of participant comments.

Fern Tree. Following the Fern Tree community bushfire Forum the Community Development Officer met with leaders of five community Fire Guard groups in Ridgeway to discuss test templates for a bushfire survival plan (subsequently to be called Household Bushfire Survival Plan). A property assessment by the local volunteer fire brigade was also arranged for one of these properties as a result of this meeting. The Community Development Officer was also invited to attend a meeting of the Bracken Lane Fire Guard group on the 28th of November, 2010. The meeting provided an opportunity for the group to discover what the Community Development Pilot entailed and if it could provide them with further support. This meeting also provided the Community Development Officer valuable insights into the Fire Guard group operations and the support it afforded its members.

As the TFS aimed to use the Pilot to determine how to more effectively support the community through tailored engagement programs, the Community Development Officer was encouraged to adapt a new, more suitable program that would facilitate the formation of community groups with the aim of becoming more bushfire prepared. This process was facilitated by the appointment of a Community Engagement Officer within the Fern Tree volunteer fire brigade. The Community Development Officer and the new Fern Tree Community Engagement Officer developed a community group template named Bushfire Ready Neighbourhood (to replace Community Fire Guard) and a complementing Household Bushfire Survival Plan to trial within the Fern Tree brigade’s response area. This trial A5 booklet provides residents with a step-by-step guide to develop their own bushfire survival plan and is designed to be completed as a whole-household activity through the facilitation of a brigade Community Engagement Officer. The plan stresses the importance of property preparation and the need to make the choice between leaving early or staying and defending. The feedback received from residents who trialled this Plan, indicates that the Household Bushfire Survival Plan could potentially be an invaluable tool for Bushfire Ready Neighbourhood group members, and other members of the community, to more easily and in greater detail, prepare their own household survival plan.

Through the support of the Community Development Pilot and through the commitment of the Fern Tree volunteer fire brigade, and especially the newly appointed Community Engagement Officer, 15 new Bushfire Ready Neighbourhoods have been formed. Through ongoing support and facilitation by the Community Engagement Officer, these group members have established ‘phone trees’ as a communication and early warning device, know what resources other community members have access to, and are aware of what their group members’ emergency plan is (i.e., who is staying to defend, and who is leaving early); invaluable information that will increase the communities’ resilience in the event of a bushfire in their area.

Bagdad. As a follow-up to the Forum, the Community Development Officer invited Forum attendees to have their properties assessed by the District Officer. A total of nine residents attended the assessment of four properties. Feedback from this initial Field Day included the benefit of confirmation from the District Officer that existing bushfire preparation and survival plans were adequate, and receiving tangible advice on how to better prepare. Again, residents highlighted the networking benefit the Field Day provided and the comfort in knowing that there are other people in the area that are also bushfire aware and prepared. Following the positive response from this earlier Field Day, the Community Development Officer organised another Field Day on the 30th October, 2010, and to encourage greater attendance, invited residents from the larger Bagdad area. A total of 28 residents participated in the Field Day assessment of four homes.

Bagdad Field day, October, 2010.

Field Day feedback surveys (n = 18) indicated that residents felt the activity was very informative, and that the format of the community assessments was valuable in that it provided specific and contextual advice on how to prepare for bushfire through various property examples (see also Table 2).

Suggested improvements for the day generally consisted of more hands-on fire training (e.g., how to use fire pump) or a specific fire training day at the local Fire Station. Others suggested that because of the benefits of the format, the Field Day should be an annual event and that more people should attend (Table 2).

Since March, 2009, over 300 community members have participated in at least one of the Pilot’s various community bushfire preparedness activities (e.g., Forum, Field Day) and received more specific and contextual bushfire mitigation information than they would have otherwise received from traditional forms of TFS education material (e.g., pamphlets, TV ads). Importantly, the District Officers supported the Pilot and attested to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

An important finding of the Pilot is that engaging community members to become more bushfire prepared is not a ‘one size fits all’ model. While most communities have the potential to become ‘bushfire prepared communities,’ some may need to bring people together to foster awareness of the need for shared responsibility and community-wide preparedness. The Pilot also demonstrated the need to develop or identify local ‘leaders’ who posses invaluable information about their community. This facilitates the ability of engagement programs that build upon existing relationships and use these resources to ensure that risk communication and education is more relevant and thus effective (Martin et al., 2007). Arguably, much of the success of the Pilot can be attributed to the Community Development Officer first engaging with leaders of the four target communities: a) to ensure acceptance, interest and commitment to the process, and b) to use their context-specific knowledge and resources to ensure that the activities that were organised were appropriate for the residents in each community. The Pilot also accommodated that, within a given community, people are at different stages of preparing (e.g., some not yet started, others at advanced levels) and helped people and groups to progressively identify individual resource and information needs and facilitate progressive preparedness.

Additionally, engaging with existing community groups provides an efficient and effective way for facilitators to obtain information about a community and their current level of bushfire risk awareness, preparedness, and motivation to mitigate negative hazard consequences (Martin et al., 2007). Increasing community involvement and the opportunity to engage in discussion of bushfire issues with other community members facilitate the kind of networking and resource sharing that is required to promote the development of sustained beliefs in the importance of preparing (Jakes et al, 2007; Paton, Johnston, Smith, & Millar, 2001; Paton & Wright, 2008). This ensures that the information provided is consistent with people’s needs and thus increases the likelihood of the sustained adoption of preparedness behaviour (Paton, 2007). The use of community engagement principles also increases trust in and the maintenance of good community-agency relationships (e.g., Ferntree-TFS). The development of the Bushfire Ready Neighbourhoods, and the appointment of the Community Engagement Officer to facilitate and guide groups through the Household Bushfire Survival Plan, is an example of how this Pilot has used hazard research findings to ensure evidence-based practice.

In December, 2010, funding was received by the Tasmanian Fire Service from the Australian Government’s Natural Disaster Resilience Program to extend the Pilot for an additional two years. The extension of the Pilot will enable consolidation of the community development work already undertaken and continue to triala range of evidence and practice-based strategies that build community connectedness and resilience, including developing the capacity of volunteer brigades to engage in community consultation and development. The benefits accruing from the Pilot, which range from more cost-effective use of agency resources to increasing the likelihood of sustained bushfire preparedness, provide a cogent argument for continuing and expanding bushfire risk communication programs based on community engagement and empowerment principles.

CFA. (2011). Community Fireguard. Available at http://www.cfa.vic.gov.au/firesafety/yourcommunity/community-fireguard.htm.

Enterprise Marketing and Research Services. (November, 2010). Baseline bushfire campaign research report prepared for the Tasmanian Fire Service. Tasmania, Hobart.

Frandsen, M. (2010). Community predictors of effective adaption to bushfire risk. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tasmania, Australia.

Jakes, P., Burns, S., Cheng, A., Saeli, E., Nelson, K., Brummel, R., et al. (2007). Critical elements in the development and implementation of community wildfire protection plans (CWPPs). The Fire Environment-innovations, Management, and Policy, Conference Proceedings, 613-624.

Johnston, D., Paton, D., Crawford, G. L., Ronan, K., Houghton, B., & Bürgelt, P. (2005). Measuring tsunami preparedness in Coastal Washington, United States. Natural Hazards, 35(1), 173-184.

Kneeshaw, K., Vaske, J. J., Bright, A., & Absher, J. D. (2004). Situational influences of acceptable wildland fire management actions. Society and Natural Resources, 17, 477-489.

Kumagai, Y., Bliss, J. C., Daniels, S. E., & Carroll, M. S. (2004). Research on causal attribution of bushfire: An exploratory multiple-methods approach. Society and Natural Resources, 17, 113-127.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2000). Correlates of household seismic hazard adjustment adoption. Risk Analysis, 20(1), 13-25.

Martin, I. M., Bender, H., & Raish, C. (2007). What motivates individuals to protect themselves from risks: The case of wildland fires, Risk Analysis, 27(4), 887-900.

McCaffrey, S. (2007). Understanding public perspectives of wildfire risk. In W. E. Martin, C. Raish, & B. Kent (Eds.), Wildfire risk: Human perceptions and management implications. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

McGee, T., & Russell, S. (2003). “It’s just a natural way of life...”: An investigation of wildfire preparedness in rural Australia. Environmental Hazards, 5, 1-12.

Paton, D. (2003). Disaster preparedness: A social-cognitive perspective. Disaster Prevention and Management, 12(3), 210-216.

Paton, D. (2007). Preparing for natural hazards: The role of community trust. Disaster Prevention and Management, 16(3), 370-379.

Paton, D. (2008). Risk communication and natural hazard mitigation: How trust influences its effectiveness. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 8(1-2), 2-16.

Paton, D., Bürgelt, P.T., & Prior, T. (2008). Living with bushfire risk: Social and environmental influences on preparedness. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 23, 41-48.

Paton, D., Frandsen, M., & Johnston, D. (2010). Confronting an unfamiliar hazard: Tsunami preparedness in Tasmania. Journal of Emergency Management Australia, 25(4), 31-36.

Paton, D., Johnston, D., Smith, L., & Millar, M. (2001). Responding to hazard effects: Promoting resilience and adjustment adoption. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 16(1), 47-52.

Paton, D., Kelly, G., Bürgelt, P. T., & Doherty, M. (2006). Preparing for bushfires: Understanding intentions. Disaster Prevention and Management, 15(4), 566-575.

Paton, D., Smith, L. M., & Johnston, D. (2003). When good intentions turn bad: Promoting disaster preparedness. Proceedings of the 2003 Australian Disaster Conference.

Paton, D., & Wright, L. (2008). Preparing for bushfires: The public education challenges facing fire agencies. In J. Handmer & K. Haynes (Eds.), Community Bushfire Safety. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing.

VBRC [2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission], (2010). Final Report: Volume II: Fire preparation. Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria.

Vogt, C. A., Winter, G., & Fried, J. S. (2005). Predicting homeowners’ approval of fuel management at the wildland-urban interface using the theory of reasoned action. Society and Natural Resources, 18, 337-354.

Winter, G., Vogt, C. A., & McCaffrey, S. (2004). Examining social trust in fuels management strategies. Journal of Forestry, 102, 8-15.

The authors wish to acknowledge the research funding received from the Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre that supported this research.

Mai Frandsen is a Doctoral student in the School of Psychology, University of Tasmania. She is investigating how community engagement influences disaster preparedness.

Douglas Paton is a Professor in the School of Psychology, University of Tasmania. His research focuses on developing and testing models of community resilience.

Kerry Sakariassen is a member of the Community Education Department of the Tasmanian Fire Service.

1 ‘Community Fireguard’ is a community development program developed by Victoria’s Country Fire Authority to assist community groups develop tailored bushfire survival strategies to help reduce loss of lives and homes in bushfires (CFA, 2011)