Disasters and crises are complex and very challenging environments for organisations. Increasingly they are impacting on organisations’ ability to achieve their objectives and the challenges are generating demands for new thinking about leading and managing. The research literature that provides insight to addressing these challenges is rapidly growing. Finding a way forward and meeting the challenges to organisations will require contributions and perspectives from a broad range of disciplines.

The release of the new risk management ISO is an opportunity to rethink how organisations can more effectively develop capability in the fields of activity described by such terms as risk management, business continuity, emergency management, crisis management, organisational resilience, continuity management, security management and disaster management. How can more effective approaches to leadership, management and governance be developed?

These fields have evolved over many years, often with little acknowledgement of the closely related and at times overlapping concepts and approaches to managing severe shocks. The use of language is particularly challenging in an environment where disciplines and professions have developed their own concepts and lexicons to articulate their particular perspectives. Many individuals and organisations have invested heavily in particular approaches and hence are often very resistant to change.

The concept of resilience seems to offer an opportunity to move thinking forward. It is however currently suffering from fad status. Consequently it will take time to settle down into an effective and robust approach to enhance organisational performance in the face of a turbulent and uncertain environment.

Organisations are a fundamental part of our society and economic system whether they are private, public or not for profits. There are very few aspects of our society and economy that don’t rely wholly or in part on the performance of organisations. They can range in size from several people through to thousands. An organisation is any entity with objectives. The dictionary definitions include “a body of persons organised for some end or work.” The challenge is how do entities continue to meet their objectives when they are under acute stress or shock? Our society and economy are almost completely dependent on incredibly complex networks or webs of organisations. These networks and webs are both physical and relational and are continually evolving and are increasingly interdependent. How shocks play out in these systems is not well understood and traditional analytical approaches seem to have limited value. Successful outcomes will depend on an interplay between organisations from the private, public and not for profit sectors. How then can the effectiveness and efficiency with which organisations deal with the risk of a severe shock be developed and enhanced?

How then can approaches be developed to deliver better outcomes for our society? Are there themes and concepts which underpin or run through the relevant disciplines that might help enhance organisational coping and adaptation to shocks? What are the opportunities to enhance organisational performance and improve the potential for an organisation to survive a shock while continuing to achieve its aims and objectives whether in the public, private or not for profit sectors?

First line of the new ISO is an excellent starting point “Organisations of all types and sizes face internal and external factors and influences that make it uncertain whether and when they will achieve their objectives. The effect this uncertainty has on an organisation’s objectives is “risk”. (AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009) This statement is significant because it links risk and objectives. A large amount of managing risk is done intuitively. Individuals use resources to deal with situations and forces which would impact on them achieving objectives for which they are responsible or want to achieve. The new international risk management standard provides a set of principles, frameworks and processes to enhance the ways individuals and organisations manage risk.

Once an entity consists of more than one individual the challenge lies in being able to effectively and efficiently manage the division of labour, so the organisation can achieve its objectives. As the organisation grows in size and complexity, an increasing proportion of available resources are needed to manage the contribution of individuals to achieve the organisation’s objectives. Objectives have to be broken or divided up into workloads for each person in the organisation to achieve. There have been many attempts over the past 50 years to minimize these overheads and to optimise resource use. This is not an argument against optimisation. It is a recognition that for most organisations it is no longer sufficient (Hamel and Valikangas 2003). A small percentage of the resource savings need to be reinvested in building the capacity of the organisation to cope with change, including shocks. Optimisation has been driven through a culture “where diligence, focus and exactitude are reinforced every day in organisations through training programs benchmarking improvement routines and measurement systems. But where is the reinforcement for strategic variety, wide scale experimentation and rapid resource redeployment?” (Hamel and Valikangas 2003:12) There have been significant gains in efficiency but this process may have generated a whole new set of risks. In recent years the rapid rise in interest in areas such resilience, risk management, governance and business continuity is evidence of these concerns.

The new ISO devotes a significant amount of space to frameworks for managing risk in organisations. The inclusion of principles and frameworks is a reflection of a growing maturity in managing risk and risk management is a essential part of good management practice. Risk and its management is an integral part of any decision or action, be it operational or strategic.

The question then arises: Can all risks be managed through the normal processes of the organisation? To state the obvious not all risks are the same, they have very different consequences and likelihoods of those consequences occurring. Some have limited effects where others can have catastrophic effects. The vast majority of risks have consequences which can and should be managed through routine processes in an organisation. However there are risks that cannot be managed in this way, the consequences are so great that business as usual is not a viable option. What approaches, structures and systems are needed to manage this group or family of risks? To achieve their objectives under these conditions a management team may have to make very rapid changes to processes and functions in order to continue to be able to meet key objectives. This also applies to upside risk where explosive growth can be just as great a challenge to the organisation.

It is the changes in the organisation that defines the concept, risks described as non routine force changes which cannot be managed through business as usual approaches or existing policy settings. If the risk does not require this significant change then it should be handled through routine processes. Typically non routine risks are low probability that is they occur rarely or in some instances have never occurred but have very high consequences for the organisation. This can be represented graphically using a risk spectrum, see fig. 1. At one end are minor risks easily managed through routine processes often described as incidents; at the other end of the spectrum are catastrophic risks and there is a threshold along the spectrum between routine and non routine risk. The threshold is defined by changes in the organisation’s or system’s performance, not on absolute values. A situation in an isolated small organisation may force it into non routine activity, whereas the same event might be a minor incident in a large organisation and easily handled through routine processes.

Figure 1. Links between approaches.

Not all shocks are the same and people use terms interchangeably or with conflicting meanings. It is useful to separate the terms by using the organisational response to the situation rather than absolute numbers.

Crisis is a very different challenge to an organisation. It does not help when the terms disaster, emergency and crisis are used interchangeably. Although clearly related, they are very different situations that prompt different questions and thinking informed by different theories. ( t’Hart & Boin 2006). A crisis is a serious threat to the fundamental values and norms of a system (or community)... “including widely shared values such as safety and security, welfare and health, integrity and fairness.” (t’Hart 2006) Crises are characterised by ambiguity of cause, effect and means of resolution (Pearson & Clair 1998:60) and stakeholders often understand crises in different ways. It is the organisation’s assumptions and understanding of its stakeholders’ behaviour that shape the organisation’s success in managing a crisis. (Alphaslan, Green & Mitroff 2009)

Both areas deal with events which are in the “un-ness” category. Unexpected, undesirable, unscheduled, unimaginable, uncertain and often unmanageable” (Hewitt 1983:p 10). Bernstein continues with the “un-ness” theme “many of these shifts may not have been unpredictable, but they were unthinkable” (Bernstein 1998:335). However not every crisis turns into a disaster but they do have the common characteristic of driving the organisation into non-routine activity.

What separates risk management in the non-routine context from the routine business practices? The non-routine part of the risk spectrum involves risks that have the potential to significantly alter the way an organisation operates until the situation is resolved. That is, to run in a non routine way or mode. That is why plans are developed and written. They are an attempt at a road map or guide for managers and staff on how to run an organisation in a very different environment that cannot be handled through normal processes and arrangements. One useful approach is to consider disasters as requiring very rapid change management to continue to achieve key objectives. To do this there may well have to be changes to the cascade of objectives through the organisation. Many middle and lower order objectives may need to be changed and significant shifts in the resources and processes to achieve the strategic objectives.

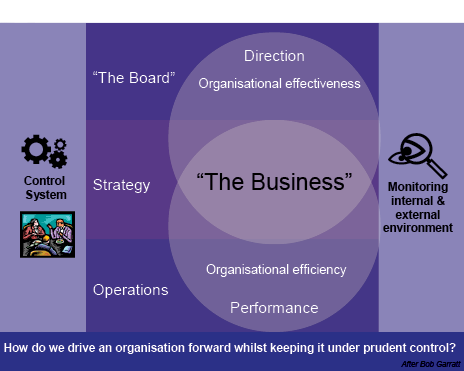

The rate of change in social, political, economic, technological and environmental dimensions of our world means we are facing more turbulent and uncertain times. The challenge is to drive an organisation forward while keeping it under prudent control (Garratt 2004). A small part of this process is building and maintaining the capability for the organisation to make very rapid changes in response to shocks but still deliver key objectives.

The OECD defines governance as “the system by which entities are directed and controlled”….and goes on to state “the structure through which the objectives of the company are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined” Risk Management is a fundamental element of governance, that is the achievement of objectives. “Risk management should ensure that organisations have an appropriate response to the risks affecting them. Risk management should thus help avoid ineffective and inefficient responses to risk that can unnecessarily prevent legitimate activities and/or distort resource allocation”. (AS/NZS ISO 3100:2009)

Risk has to be managed to achieve any objective; from the board room to the mail room all people in an organisation have responsibilities and they have to manage risk to achieve those objectives. Whatever classification or terms used are to categorise risk (strategic, environmental, security or operational) do not really matter, the crucial concept, the risks people face, depends on the nature of their responsibilities and objectives they have to meet.

In most organisations, groups of individuals have to work collectively to achieve many objectives and managing risk should be no different. One key challenge is how, then, can collective action be reorganised so that objectives can continue to be met when the system has been affected by a non-routine risk or shock.

Figure 2. Governance framework.

Diagram above outlines a generic governance framework ( Garratt 2004). The term “the business” is used to describe what the organisation is trying to achieve or set up to do. While the diagram was originally designed for a private sector audience it is applicable to any reasonably sized organisation. There are two broad functions in any organisation and they are directing and operations. The “directors” chart the vision and mission of the organisation; they could be a board, minister, public representatives e.g. councillors etc. It is the function they perform that is important. This part of the organisation sets the direction and makes adjustments in response to changes in the internal and external environment they are therefore mainly involved in managing strategic risks. The executives and management team use resources to achieve the mission or vision of the organisation under the direction of the “Board”. This part of the organisation can be described as operations. The two groups come together to develop strategy to ensure that the organisation can achieve its objectives.

Organisations have become very skilled at cascading the responsibility for the achievement of objectives from the board down to the shop floor. What organisations have not been good at is tying responsibility for achieving objectives with responsibly for managing risk. “To be effective within an organisation, risk management should be an integrated part of the organisation’s overall governance, management, reporting processes, policies, philosophy and culture.” (AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009)

There has been a growing interest in the organisational response to non routine risk. Whether it is risk management, business continuity or crisis management, the emergence of interest in these fields is a good measure of increasing concerns in this area. The governance challenge is how to reconcile the divergence or lack of coherence between the fields that have evolved to deal with organisational response to risk of shocks. There appears to be little research about how these various perspectives can be integrated within an effective governance framework. This issue is rarely addressed in the organisational literature so carrying out research in this area will be very important.

There is a fundamental challenge for organisations in rapidly changing to fit a new environment and their core function. They were conceived primarily as devices for reducing uncertainty (Simon 1961 and March and Simon 1958) “They achieve this by creating zones of stability, structures that can maintain their identity over time in the face of external variations”. (Boisot 2003:54). However if the external variation is a shock, then expecting organisations to seamlessly shift from one state to another, is at best problematic. If organisational survival depends on the rate of learning being greater than the rate of change in the environment, then a crisis or disaster with a very rapid rate of change and very compressed timeframe, can be very challenging. (Ashby 1958)

Non-routine risks generate conditions where numbers of people and organisations (some times large) have to work together in a non-routine way. In many cases they may not have even met each other before, much less be experienced in working together (Borodzicz 2005). The range of tasks, objectives and working environment may be substantially different from their normal workplace. “It is vital that the people involved in the response have received sufficient opportunity beforehand in the planning stage to form effective relationships with those people that the emergency will thrust together intra-and inter-organisationally”. (Crichton, Ramsay and Kelly 2009:33).

The challenge is what organisational structures or system would be appropriate for an organisation that has to make very significant changes in the way it uses assets, people and other resources that is operate in a non-routine way. Approaches such as Incident Control Systems (ICS) or Incident Management Systems (IMS) have been developed over many years in an attempt to address this challenge. The initial work on ICS was carried out by the fire services in the USA in the mid 1970’s. Other variations include the Gold, Silver and Bronze system developed in England in 1985 when Scotland Yard realised that their usual rank system was inappropriate for sudden events. In this case the driver was the limitations of day to day or routine organisational structures to manage unfamiliar events. A detailed discussion of these systems is beyond this paper but interest in their effectiveness is growing. (Arbuthnot 2008) (Devitt and Borodzicz 2008) (Uhr Johansson and Fredholm 2008) (Webb and Neal 2006)

The trends are clear, turbulence, complexity and uncertainty in our environment are only going to grow. Sentinels and researchers in many fields have clearly flagged the issue and enunciated many of the pressing challenges. At the heart of the problem is the organisation; the building block of our society and economy. How can sufficient learning and capacity-building keep up with change? How can effective transformational and adaptive capacity become institutionalised and a core part of good governance of organisations? (Podger 2004) (Kettl 2003) (Hamel 2003) (Garratt 2004). “Taking this broader view which sees learning as a cultural activity of organisations helps us explore a less instrumental more reflexive aspect of institutional resilience in the face of the future.” (Turner and Pidgeon 1997:195). Learning and capability development are key themes that emerge from researchers and thinkers across this incredibly broad and diverse field, whether at individual, team or organisational levels.

Alphaslan, C., Green, S. & Mitroff, I. (2009) Corporate Governance in the context of Crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management vol 17 (1)

Arbuthnot, K. A (2009) Command Gap? Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 16 (4) 186-194)

Ashby, W.R. (1958) Self regulation and Requisite variety in Introduction to Cybernetics Wiley London.

Bernstein, P. (1998) Against the Gods Wiley New York

Boin, A. ‘t Hart, P. Stern, E. Sundelius, B. (2006) The Politics of Crisis Management Cambridge University Press Cambridge

Boin, A. ‘tHart, P., (2006) The Crisis Approach in Rogriguez, H., Quarrantelli, E.L. and Dynes R.R. (Eds) Handbook of Disaster Research, New York, Springer.

Boisot, M. (2003) Preparing for Turbulence: in Garratt, B. (Ed) Developing Strategic Thought. London, Profile Books.

Borodzicz, E., (2005): Risk, Crisis and Security Management Chichester Wiley.

Coles, E. Smith, D. & Tombs, S. Eds (2000) Conceptualising Issues of risk management within the ‘Risk Society’ Risk Management and Society, Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Crichton, M. Ramsay, C. and Kelly, T. (2009) Enhancing Organisational Resilience Through Emergency Planning Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management Vol 17 (1)

Devitt, K. and Borodzicz, E., (2008) Interwoven Leadership: the missing link in Multi-Agency Response Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management Vol 16 (4)

Drennan, L.T. McConnell, A., (2007) Risk and crisis management in the public Sector Routledge. New York.

Garratt, B. (1999) The learning organisation 15 years on some personal reflections. The Learning Organisation. Vol 6 (5)

Garratt, B. (2003) (Ed) Developing strategic thought, London Profile Books

Garratt, B. (2006) Thin on Top: Why Corporate Governance Matters Nickolas Breatley London

Hamel, G. Valikangas, L. (2003) The Quest for Resilience Harvard Business Review Sept 2003

Hewitt, K. (1983) (ed). Interpretations of calamity London Allen and Unwin

Kasperson, R. (1992) The Social Amplification of Risk. in Krimsky, S and D. Golding (1992). (eds) Social Theories of Risk. Westport Preager

Kettl (2003). The Future of Public Administration Report of the Special NASPAA/American Political Science Association Task Force.

Kreps, G. and Bosworth (2006) Organisational Adaptation to Disaster in Rogriguez, H., Quarrantelli, E.L. and Dynes R.R. (Eds) Handbook of Disaster Research Springer, New York, pp 295-315

Lagadec: (1997) Learning processes for Crisis management in complex organisations Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 5 (1) 24-31

Neal, D. M. and Webb, G. R. (2006) Structural Barriers to Implementing the National Incident Management System during the Response to Hurricane Katrina http://www.colorado.edu/hazards/publications/sp/sp40/katrina_TOC.pdf

Pearson, C.M. & Clair, J.A. (1998) Reframing Crisis Management Academy of Management Review Vol 23 (1)

Podger, A. (2004) Innovation with integrity – the public sector leadership imperative to 2020. Australian Journal of public administration 63 (1)

Simon, H (1961) Administrative Behaviour. New York Macmillian.

Smithson, M. (1991). Managing in the Age of Ignorance New Perspectives on Uncertainty and Risk Canberra CRES/NDO.

Turner, B. and Pidgeon, N. 1997 Man made disasters. London Wykeham

Uhr, C. Johansson, H. and Fredholm, L (2008) Analysing Emergency Response Systems Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 16 (2)

Michael Tarrant is the Assistant Director, Research Management at the Australian Emergency Management Institute. He also holds adjunct appointments in the Department of Tropical Medicine at James Cook University and in the Public Health Faculty at Queensland University of Technology. He is a member of the Community of Interest for Organisational Resilience.

He has worked at a national level as member of Standards Australia Risk Management Committee (OB-007) since 1998 and contributed to wide range of associated handbooks.