Howell & Rohan examine the critical role that traditional and new media played in the communication program for the geographically widespread equine influenza crisis in Australia in 2007.

PAPER ORIGINALLY PRESENTED AT THE 2009 EMPA CONFERENCE

Crisis communications is the dialogue between the organisation and its publics prior to, during, and after the negative event (Fearn-Banks, 2002). It is emphasised that “communicating does not simply mean being able to send messages, it also means being able to receive them” (Lagadec, 1993 p.14). It is important that crisis communications are quickly actionable as typically “the public will quickly begin to look for a trusted and consistent source of information” (Russell, cited in Galloway and Kwansah-Aidoo, 2005, p.95). Best practice crisis communications is designed to maintain public confidence and minimising damage suffered (Levine, 2002).

Public relations practitioners are expected to integrate all means of communication in their profession and to demonstrate ongoing best practice. The growth of the World Wide Web (the Web) has led to an upsurge in the supply of information and content that has affected how public relations practitioners practice. New media such as organisational web sites are used to keep publics informed, provide information to the media, gather information about publics, and seek to strengthen corporate identity. Traditionally, most Fortune 500 companies use Web sites for external communication, focusing on promoting the company image and enhancing public relations (Chang et al, 1997). With the advent of blogosphere, Web 2.0, and social media sites like, Flickr, Twitter, Blogger, Facebook and MySpace, public relations practitioners are confronted with an ever-changing communication landscape.

Crisis communications practices have expanded to use traditional and new media to communicate their key messages to key publics (Arpan & Pompper, 2003; Fearn-Banks, 2002). It is commonly suggested that new media have drastically altered the way organisations communicate during a crisis (Kimmel, 2004) and that crisis communication has evolved with the digital revolution to instantaneous, exhaustive, global information required about the crisis by key publics (Barr, 2000). A comparatively early and prominent example of crisis communications and technology occurred during the aftermath of 9/11 with employees displaced from the World Trade Centres logging into their company websites to gather information to supplement that found in the traditional media channels such as radio, television and print. The Web implies the immediacy of the radio and the persistence of print, and thus has far-reaching implications for public relations practitioners.

Public relations researchers have provided valuable analysis and insight how the Web can assist or hinder organisations in their crisis communication (Coombs, 2000; Hearit, 1999; Martinelli & Briggs, 1998; Witmer, 2000). For example, a 2005 study from Oxford University found that more than 90 percent of communication may not be owned or controlled by the organisation in focus (Kirk cited in Cincotta, 2005).

Although much of the recent research has focused on the affect and impact of new media, it should be remembered that all media can play a role in crisis communication, (c.f. Taylor & Perry, 2005; Taylor & Kent, 2007). A review of the presence of traditional and new communication tools in crisis communications identified that traditional public relations tactics such as news releases were still the most prevalent tactics employed (Taylor and Perry, 2005). New media tactics including websites and informational links were used far less frequently (Taylor & Perry, 2005).

Crises are a prominent feature of business and government environment and the potential to damage any organisation (Baker, 2001; Mitroff & Alpasian, 2003; Olaniran & Williams, 2001; Pauchant & Mitroff, 1992). In the past decade, there have been a number of substantial disease outbreak crises reported including: the United Kingdom 2001 Foot and Mouth outbreak, the 2003 SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic in Asia and Canada, and the 2004 appearance of BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) or mad cow disease in United States and Canada. Not only have these disease outbreaks been unpredictable and impacted viability, credibility and reputations (Baker, 2001; Mitroff, Shrivastava, & Udwadia, 1987), they have lead to the realisation that health crises communications can restrict the spread of infections and help save the lives of people and animals. This paper investigates the impact of both traditional and new media and the role they play in communication during a geographically widespread animal health crisis, the Australian Equine Influenza outbreak.

This paper uses case-based methodology to explore how traditional and new media channels can be used by public relations professionals to best manage a crisis. In the Equine Influenza (hereafter EI) case examined, public relations practitioners relied on a number of different media to communicate to key publics about a matter of potentially great public interest (i.e. EI). The organisation reviewed is the New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (hereafter DPI). The paper examines how using media releases and DPI’s web site enhanced the success of the crisis strategy. Publicly available documents and media reports were reviewed to examine the DPI’s communication strategy and the tactics it used to manage the media and key publics before, during and after the EI threat. Further, material submitted to the Public Relations Institute of Australia 2008 Golden Target Awards in New South Wales was also utilised for this paper.

During the event, the Federal Government spent more than $A342 million eradicating the virus and providing financial assistance to affected individuals, organisations and clubs (Burke, 2008). It is suggested that the total cost the outbreak resulted “in a loss to the horse industry and the community of something in the order $1 billion” (Harding cited in ABC, 2008 pg.7). The 2007 EI crisis can be categorised as a serve crisis using the Pauchant and Mitroff’s 1992 matrix and was created through a series of technical and human errors.

The 2007/08 EI outbreak in New South Wales was the most serious emergency animal disease Australia has experienced (DPI, 2008a). Due to the infection, horses became sick and to prevent the virus spreading horse movements were banned. As a direct result, a range of horse events were cancelled and farriers, strappers, feed suppliers, vets and even milliners were put out of work. There was a call for the Melbourne Cup, Australia’s richest and internationally renowned horse race to be postponed as horses from New South Wales were withdrawn from the Spring Racing Carnival due to illness.

The equine industry is estimated to generate approximately $A9billion each year and employ tens of thousands of people. At the peak of EI, 47,000 horses were infected in NSW on 5943 properties, and horse owners from pony clubbers through to thoroughbred racing community were directly affected.

The campaign to eradicate the disease, led by the DPI, was the largest of its type ever undertaken in Australia and using the latest laboratory, vaccine, surveillance, mapping and communication technologies (DPI, 2008a). The effective management of EI required the public to have confidence in the ability of the DPI to contain and eradicate the disease. The need for proactive public relations was recognised as a crucial aspect of the EI containment and eradication strategy.

Diligence is an essential aspect of effective public relations. Communication strategies will only be successful if all avenues are explored and public relations practitioners are prepared for the unexpected (Fearn-Banks, 2002). Effective crisis communication management is based on how rapidly an organisation can respond to a crisis, requiring an organisation to act in a proactive manner to best manage potentially dangerous situations and issues (Cincotta, 2005; Hendrix, 2001; Nolan 2006; Stacks, 2005). The DPI’s proactive response to the EI threat reflected the need to place public interest and safety above financial costs.

The concept that crises progress in a certain manner or follow a life cycle was first identified in the early 1980’s (Fink, 1986) and expanded to five stages; these being: prodromal, prevention, acute, chronic and resolution (Fearn-Banks 2002; Mitroff, 1996) during the 1990s. The five stage crisis model is applied to the EI case with a synopsis of each stage that includes the key messages being examined in terms of content and impact. Thus, the DPI’s key messages and channels of communication are identified and documents for the EI crisis.

The prodromal stage is defined as the warning or pre-crisis stage (Fink, 1986). Initially, clues or hints of a potential crisis begins to emerge and are identifiable (Coombs, 1999).

Quarantine has played a critical role in reducing the risk of disease in Australia and Australia is one of the few countries to remain free from many of the world’s most severe pests and diseases (AQIS, 2009). In early 2007 there had been an outbreak of EI in Japan. Many of the stallions exposed to EI were designated to attend Australia for annual breeding season. EI acute is a highly contagious viral disease that can rapidly spread outbreaks of respiratory disease among populations of horses, donkeys, mules and other equine species (CSIRO, 2007).

Johnson and Zawawi (2002) suggest that a lack of anticipation and preparation can increase the difficulty for public relations practitioners to negate negative perceptions. Further, Coombs (1999) asserts that “not all crises can be prevented, so organisational members must prepare” (p.219). Academics and practitioners assert that best practice for crisis management is proactive. Matera and Artigue (2000) recommend “if management regards public relations functions as important, then the chances are good that a corporation can successfully emerge from disaster” (p. 216).

The DPI was involved in the development of the Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan, AusvetPlan, which outlines the role of the public relations in the case of an emergency animal disease threat. This plan was employed during the EI crisis. Further, the DPI media team had established and maintained a strong working relationship with key publics through their day-to-day role communicating with rural industries.

The Acute or crisis breakout is the most intense stage of the crisis (Fink, 1986). Is also likely to be the shortest stage in which the trigger theme evolves into an actual crisis (Howell & Miller, 2006).

On 24 August 2007, a veterinarian reported to NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) that he had observed sick horses at Centennial Park in Sydney. Holloway and Betts (2005) suggest that when there is an immediate threat to individuals’ (and in this case livestock) safety, an organisation will rarely have time to gather all information relevant prior to facing the press.

The NSW Chief Veterinary Officer imposed an immediate state-wide horse movement ban and established a State Disease Control Headquarters at Orange and a Local Disease Control Centre at Menangle (DPI, 2008b). The ban on horse movements was simultaneously extended across the whole country. Financial penalties were announced to reinforce the ban.

In the first week of the EI crisis there were 943 broadcast items and 109 press articles relating to EI. The high level of coverage tends to mirror the intensity of the stage of the actual crisis in crisis life-cycle model. During this intense period, it is vital the organisation responds to media requests and maintains control of the message. Proactive media management is required, with clear concise information released in a timely manner. The DPI undertook a blanket media communication approach targeting metropolitan, regional and horse-industry specific media. More than 59 media releases were generated and media conferences were staged throughout the state of NSW during the acute stage of the crisis from August 24 to August 31, 2007. A telephone service with a 1800 EI hotline was established to assist key publics, provide individual information and track key messages as they were released into the media. Further, DPI engaged in the development of radio, television and print advertising in order to spread the intended message. A DPI specific webpage linked to the organisational website was developed along with series of public information meetings. All the information provided at these meetings and on the website was translated into Fact Sheets and disseminated in print at saddleries, rural stores, through Forward Command Posts, private veterinarians and NSW DPI offices (DPI, 2008a). The DPI also used new media with the audio interviews with Chief Veterinary Officer posted to website and accessed by media. The Industry liaison staff monitored and contributed to blogs and horse-industry web pages (DPI, 2008a). Further, video footage was distributed to television networks via email, and the DPI developed a lists of 12,000 direct emails used for updates during the crisis.

Coombs (2004) suggests that the effects of the crisis linger as efforts to defuse the crisis progress. During this stage, Fearn-Banks (2002) recommends that the organisation undertake an audit of the events, activities and mass media coverage of the crisis to date, and seeks to exploit successful management activities and learn from failures.

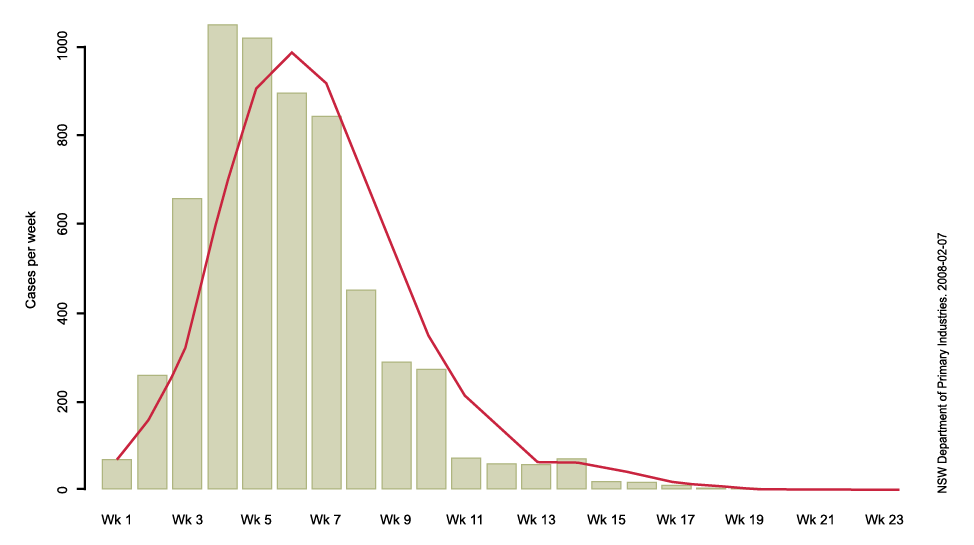

As illustrated in Graph 1 Weekly epidemic curve for NSW, the number of new infected premises recorded each week of the outbreak to the end of December 2007. A 3-week rolling average number of new cases is shown with the continuous line and indicates that the rate of new infections peaked on 24 September, or week 5 of this illustration.

GRAPH 1. Weekly epidemic curve for NSW to 2008

The infection continued to spread during September 2007 but had been contained. At end of October a declining rate of new infections indicated that the DPI control strategy was containing EI. On 1 February, 2008 interstate movements were freed up, and large parts of NSW were changed to a ‘white zone’ indicating their effective freedom from EI infection (DPI, 2008b). In September 2007, the then Prime Minister John Howard announced that there would be a full, independent inquiry into the outbreak of equine influenza the Hon Mr Ian Callinan AC was appointed to head a Royal Commission by the then Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

Fink (1986) asserts that the resolution stage is when the immediate effects of the crisis have passed, and the organisation returns to business as usual (Coombs, 1999). The state of NSW was finally declared free of EI in February. The disease was eradicated within six months well ahead of predictions and by July 2008 horse industry operations had returned to normal.

Callinan’s Royal Commission’s report made 38 recommendations regarding changes to quarantine regulations and the horse industry: all of which were accepted by the Federal Government. In Commissioner Callinan’s report it was concluded that the virus ‘probably’ came into Australia in August 2007, via horses from Japan (Burke, 2008). However, it was not possible to “make a precise finding as to how the virus entered the general horse population, or of direct liability or culpability, but found the virus was most likely carried on a contaminated person or equipment leaving Eastern Creek Quarantine Station” (Burke, 2008, p.1).

In summary, during the EI crisis the DPI issued over 300 media release, including 59 in the first seven days. There were thousands of radio and television interviews conducted and more than 58 media conferences and media events were staged. The DPI’s website provided the most comprehensive equine influenza information resource nationally, generating up to 2000 visits a day. By the end of the crisis there were 685,000 unique ‘page views’ generated for the EI home page. In addition, there were other web pages covering the topic, fact sheets and multimedia products available from the EI website (DPI, 2008b). Further, audio interviews were posted to website and accessed by media, and industry liaison staff monitored and contributed to blogs and horse-industry web pages.

As demonstrated by the messages developed for the EI campaign, crisis communication involves the transmission of messages on the nature of crises. The messages developed by the DPI were designed to alleviate problems in the exchange of information about the nature, magnitude, significance, control, and management of risks to key publics (Covello, Hyde, Peters, & Wojtecki, 2001).

Saffir (2000) suggests that “words and actions under that instant pressure cannot be recalled…if they are unwise, they can seriously damage or doom any subsequent effort to recoup” (p.109). Because the DPI had undertaken extensive planning and research, the DPI was able to respond quickly and use traditional and new media to quickly communicate with key publics.

Throughout the crisis the DPI were consistent and coherent in their communication. They employed an open, honest and direct communication pattern with the key publics. Gibson (2001) suggests that “it’s very important that the public gets consistent straight forward messages…one person [will ensure that] the lines [messages] will be exactly the same in each interview, whether it’s a talk-back radio, a newspaper or television” (cited in Barrett, 2001, p.1). Throughout the crisis the DPI maintained the same, consistent message. The DPI employed Minister Ian Macdonald and DPI Chief Vet Dr Bruce Christie to present the key messages. In an analysis of the media coverage, Minister Ian Macdonald was the most prominent spokesperson in the press coverage analysed, quoted in 38% of the coverage (DPI, 2008c). DPI Chief Veterinarian Dr Bruce Christie was also acknowledge as the leading ‘expert’ spokesperson, providing detailed information on the spread and nature of the disease and DPI’s efforts to minimise the spread of EI (DPI, 2008c).

Radio was the first electronic communication channel used by public relations pioneers to communicate with key publics in the mid 1920’s. Radio remains the one of the best sources for instant message exposure during a crisis event. As part of disaster planning, all emergency services continue to advise that individuals should ‘listen to the radio’ to gain further information (Energex, 2009). Though radio seems like a medium decline when compared to the ascension and attention given to new technology, radio remains extremely effective in audience pull and an excellent instantaneous channel of communication to key publics. Radio formats are very specific and as such the audiences tend to be very different (Cutlip, Center and Broome, 2006). Smith asserts that “when radio audiences do listen, they focus on what is being said” (Smith, 2005, p.188). For the EI crisis “radio was vital, and probably our most important communication tool, to ensure up to the minute information was relayed to our key publics” (personal communication, Brett Fifeld February 23, 2009).

Curtin, Hayman and Husein (2005) suggest that if managed well, a crisis can actually bring benefits to an organisation. A crisis can also prove to be an opportunity for a organisation to reinforce its commitment to its key publics (Doeg, 2005). The manner in which DPI addressed the EI crisis is an example of best practice using traditional and new media to communicate with key publics and track the strategy’s effect throughout the crisis. The DPI’s reputation with its key publics was strengthened as a result of a well-managed crisis communication strategy.

DPI Website Equine Influenza Information

The Public Relations Institute of Australia awarded a Golden Target Award to the DPI. In doing so the Institute recognised the outstanding work and strategic involvement by the DPI (NSW) on this critical issue as it posed a significant threat to the economic well-being and/or continued viability of the entire industry.

During an extremely difficult time for the equine industries, the DPI proved to be an effective communicator using simplicity and repetition of the key message that there should be ‘no horse movement’ and the provision of facts as the situation unfolded. This strategy minimized speculation or uncertainty at a time of widespread concern. Further, the DPI maintained the established strong relationship with the NSW media throughout the crisis, providing continuous and comprehensive responses to issues as they arose. This ensured that the media itself was not left to speculate on how to respond to the crisis and that its focus was on publicising preventive measures rather than spreading panic.

Communication effectiveness is judged on its ability to satisfy the needs of publics (Heath, 2001). The equine industry’s stakeholders are diverse and wide ranging, yet during the crisis the communication strategy ensured that all stakeholders were provided with extensive information, and cognition of the information provided was high. This case study demonstrates how the DPI used traditional and new media to communicate key messages throughout the crisis. They found that radio provided the most useful channel to ensure the key publics were kept aware of developments during the crisis (personal communication, Brett Fifeld February 23, 2009). Further, the research undertaken by the DPI provided a rich source of information in the development of the crisis communication activities implemented by the Department during the crisis. This paper validates the use all forms of media during a crisis situation and demonstrates radio’s value in terms of producing better outcomes for the organisation in terms of communication.

Campbell (1999) views the crisis process as one of continual improvement. That is also true for public relations research and practice. Averting a crisis is the greatest success for any public relations professional (Howell & Miller, 2006). But if a crisis does occur, an organisation can be well prepared with a sound integrated crisis communication strategy using both traditional and new media can ensure quality outcomes.

ABC. (2008). Horse industry calls for more quarantine funding, ABC Premium News. Sydney: December 18, 2008. Retrieved 18 January, 2009 from http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/12/18/2449573.htm

AQIS, (2009). Quarantine in Australian. Retrieved 23 January, 2009 from http://www.daffa.gov.au/aqis/quarantine

Arpan, L. M., & Pompper, D. (2003). Stormyweather: testing ‘stealing thunder’ as a crisis communication strategy to improve communication flow between organisations and journalists. Public Relations Review, 29(3), 291–308.

Baker, G. F. “Race and Reputation: Restoring Image Beyond the Crisis” in Heath, R L. 2001 (Ed) Handbook of Public Relations, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Barton, L. (1993). Crisis in Organisations: Managing and Communicating in the heat of Chaos. Cincinnati, Ohio: South-Western Publishing Company.

Barr, T. (2000). newmedia.com.au. St Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Burke, T. (12 Jun 2008) Government releases Equine Influenza Inquiry report. Media Release. Retrieved February 24, 2009 http://www.maff.gov.au/media/media_releases/2008/june_2008/government_releases_equine_influenza_inquiry_report

Cameron, D. (2001, April 13) Ansett’s long haul to clear the air. The Sydney Morning Herald pp.1–2.

Campbell, R. (1999). Crisis control: Preventing & managing corporate crises. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Group (Australia).

Cincotta, K. (2005, October 31). Less fluff more facts, industry learns. B&T: News. Retrieved 8 May 2006, from http://www.bandt.com.au/news/bd/0c037bbd.asp.

Common, G. (2005). Crisis and Issues Management- three recent examples show it impact on perception and reputation. PR Influences. Retrieved July 20, 2006, from www.prinfluences.com.au/index.php?artId=602

Coombs, W.T. (1999). Ongoing crisis communication: planning, managing, and responding. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Coombs, W.T. (2004). Impact of Past Crises on Current Crisis Communication: Insights from Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Journal of Business Communication, 41 (3), 265-289.

Coombs, W.T., & Holladay, S. (2002). Helping Crisis Managers Protect Reputational Assets: Initial Tests of the Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16,2, 165-186. Retrieved July 18, 2006, from ABI/INFORM Global database.

Covello, V.T., Hyde, R.C., Peters, R.G., Wojtecki, J.G. (2001). Risk Communication, the West Nile Virus Epidemic, and Bioterrorism: Responding to the Communication Challenges Posed by the Intentional or Unintentional Release of a Pathogen in an Urban Setting. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 78 (2), 382-391.

CSIRO (2007). Equine influenza. Fact Sheet. Retrieved February 23, 2009 from http://www.csiro.au/resources/EquineInfluenza.html

Curtin, T. Hayman, D., Husein, N. (2005). Managing a crisis: a practical guide New Jersey: John Wiley

Cutlip, S. M., Center, A. H. & Broom, G. M. (2006). Effective public relations (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Derrig, L. (2008). Equine influenza report reveals National biosecurity must be improved. Media Release, NSW Government. Retrieved February 14, 2009 from http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/archive/news-releases/agriculture/2008/equine-influenza-report

DPI (2008a). Stamping out horse flu. Golden Target Awards 2008. Retrieved January 30, 2009 from http://www.pria.com.au/resources/list/asset_id/326/cid/352/parent/0/t/resources/title/Stamping%20Out%20Horse%20Flu

DPI (2008b). Summary of the 2007/08 Equine Influenza Outbreak. Factsheet Retrieved January 30, 2009 from http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/livestock/horse/influenza/summary-of-the-200708-ei-outbreak

Energex (2009) Storm Safety Check List. Retrived February 12, 2009 from http://www.energex.com.au/safety/safety_storm_checklist.html

Fall, L.T. (2004). The increasing role of public relations as a crisis management function: An empirical examination of communication restrategising efforts among destination organisation managers in the wake of 11th September 2001. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10 (3), 238-252.

Fearn-Banks, K. (2002). Crisis Communications: A casebook approach (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fink, S. (1986). Crisis management: planning for the inevitable. New York, N.Y.: American Management Association.

Gonzalez-Herrero, Alfonso, Pratt, Cornelius, B. (1995). How to manage a crisis before-or when-it hits. Public Relations Quarterly, 1, 25-30. Retrieved July 20, 2006, from ABI/INFORM Global database.

Grunig, J.E. (1990). Theory and Practice of Interactive Media Relations. Public Relations Quarterly, 35 (3), 18-23.

Grunig, J.E. and Hunt, T. (1984). Managing Public Relations. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Grunig, J.E. and Repper, F.C. (1992). Strategic Management, Publics, and Issues. In J.E Grunig (Ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communications Management (pp. 117-157). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gurau, C., Serban, A. (2005). The anatomy of the product recall message: The structure and function of product recall messages published in the UK press. Journal of Communication Management, 9 (4), 326-338.

Heath, R.L & Millar, D.P. (2004). Responding to Crisis: A Rhetorical Approach to Crisis Communication. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Heath, R.L. (2001). Handbook of Public Relations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hendrix, J. (2001). Public Relations Cases, (5th ed.) Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Howell, G., Miller, R. (2006). How the relationship between the crisis life cycle and mass media content can better inform crisis communication. Prism 4(1). http://praxis.massey.ac.nz/fileadmin/Praxis/Files/Journal_Files/2006_general/Howell_Miller.pdf

Johnson, J. & Zawawi, C. (eds). (2002). Public Relations: theory and practice. Sydney: Allen & Unwin

Kimmel, A. J. (2004). Rumours and rumour control: A manager’s guide to understanding and combating rumours. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chang, L., Arnett, K.P, Capella, L.M. & Beatty, R.C. (1997), Web Sites of the Fortune 500 Companies: Facing Customers Through Home Pages. Information & Management 31 (1997), pp. 335–345

McElreath, M. (1997). Managing strategic and ethical public relations campaigns (2nd. ed.). Dubuque, IA: Brown & Benchmark.

Matera, F., & Artigue, R. (2000). Public Relations campaigns and techniques: Building Bridges into the 21st Century. USA: Allyn & Bacon.

Messara, J. (2008). A National Discussion: Equine Biosecurity Managing the risk of and responding to a future incursion of Equine Influenza. Proceedings Retrieved January 24, 2009 from http://www.animalhealthaustralia.com.au/shadomx/apps/fms/fmsdownload.cfm?file_uuid=1A0FA45F-A9D7-8BEF-7F55-A4ED532B8BD4&siteName=aahc

Mitroff, I.I. (1996). Essential Guide to Managing Corporate Crisis: A Step-by-Step. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mitroff, I. I., & Alpasian, M. C. (2003). Preparing for evil, Harvard Business Review, 81(4), 109–115.

Mitroff, I.I., Shrivastava, P. & W.A. Udawaia. (1987). Effective crisis management. The Academy of Management Executive 1(3): 283-292.

Michelson, G., & Mouly, S. (2002). ‘You didn’t hear it from us but…’: Towards an understanding of rumour and gossip in organisations. Australian Journal of Management, 27(Special Issue), 57-65.

O’Neil, J. (2005). Public relations educators access and report current teaching practices. Monograph 68 Fall, 1-4.

Olanrian, B. A., & Williams D. E. (2001). Anticipatory model of crisis management: A vigilant response to technology crises. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 487–500). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pan, Z., & Kosicki, G. M. (1993). Framing analysis: An approach to discourse. Political communication 10, 55–75.

Patterson, B. (2004). A crisis media relations primer. Public Relations Tactics, 11(12), 13.

Pauchant, T.C. & Mitroff, I.I. (1992). Transforming the crisis-prone organisation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rawlins, B.L. (2006). Prioritising Stakeholders for Public Relations. Institute for Public Relations. http://www.instituteforpr.org/pdf/Rawlins_Prioritizing_Stakeholders.pdf.

Russell, S. (2005) in Galloway, C. and K. Kwansah-Aidoo (2005) Public Relations Issues and Crisis Management Thomson Social Science Press, Victoria.

Saffir, L. (2000). Power public relations: how to master the new PR. (2nd ed.) Lincolnwood, Ill: NTC Business Books.

Smith, R.D. (2005). Strategic Planning for Public Relations. New York: Routledge.

Stacks, D. (2002). Primer of Public Relations Research. New York: Guildford Press.

Sturges, D. L. (1994). Communication Through Crisis : A Strategy for Organizational Survival. Management Communication Quarterly, 7(3), 297-317.

Taylor, M. & Perry, D.C. (2005). Diffusion of traditional and new media tactics in crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 31 209-217

Taylor, M. & Kent, M.L. (2007). Taxonomy of mediated crisis responses. Public Relations Review. 33 (12), 140-146.

Ulmer, R.R. (2001). Effective crisis management through established stakeholder relationships Malden Mills as a case study. Management Communication

Weiner, B. (1985). An attribution theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548-573.

Wilcox, D.L., Cameron, G.T., Ault, P.H., Agee, W.K. (2006). Public Relations: Strategies and Tactics (8th ed.). Boston, M.A.: Pearson Allyn and Bacon.

Gwyneth V.J. Howell, The University of Western Sydney

Rohan Miller, The University of Sydney

Dr Gwyneth Howell is the senior academic for the Public Relations Major at the University of Western Sydney. She has extensive experience and an international research profile in strategic public relations, crisis and issues management and her current research focus is new media.

Email: g.howell@uws.edu.au